Inference in First-Order Logic

Propositional vs. First-Order Inference

One way to do first-order inference is to convert the first-order knowledge base to propositional logic and use propositional inference.

The rule of Universal Instantiation (UI) says that we can infer any sentence obtained by substituting a ground term for a universally quantified variable.

Let \(\text{SUBST}(\theta, \alpha)\) denote the result of applying the substitution \(\theta\) to the sentence \(\alpha\). Then the UI rule is written

\[ \frac{\forall v \ \alpha}{\text{SUBST}(\{ v / g\}, \alpha)} \]

for any variable \(v\) and the ground term \(g\).

For example, from

\[ \forall x \ \text{King}(x) \land \text{Greedy}(x) \implies \text{Evil}(x) \]

we can infer

\[ \text{King}(John) \land \text{Greedy}(John) \implies \text{Evil}(John) \]

Similarly, the rule of Existential Instantiation replace an existentially quantified variable with a single new constant symbol. The formal statement is as follows: for any sentence \(\alpha\), variable \(v\), and constant symbol \(k\) that does not appear elsewhere in the knowledge base,

\[ \frac{\exists v \ \alpha}{\text{SUBST}(\{ v / k\}, \alpha)} \]

for example, from

\[ \exists x \ \text{Crown}(x) \land \text{OnHead}(x, John) \]

we can infer

\[ \text{Crown}(C_1) \land \text{OnHead}(C_1, John) \]

as long as \(C_1\) does not appear elsewhere in the knowledge base.

Reduction to Propositional Inference

Any first-order knowledge base can be converted into a propositional knowledge base. An existentially quantified sentence can be replaced by one instantiation, a universally quantitified sentence can be replaced by the set of all possible instantiations.

For example, suppose the knowledge base contains the following sentences:

\[ \begin{align*} & \forall x \ \text{King}(x) \land \text{Greedy}(x) \implies \text{Evil}(x) \\ & \text{King}(John) \\ & \text{Greedy}(John) \\ & \text{Brother}(Richard, John) \end{align*} \]

the only objects are \(John\) and \(Richard\). Applying UI to the first sentence using all possible substitutions, \(\{x / John\}\) and \(\{ x / Richard \}\) gives

\[ \begin{align*} & \text{King}(John) \land \text{Greedy}(John) \implies \text{Evil}(John) \\ & \text{King}(Richard) \land \text{Greedy}(Richard) \implies \text{Evil}(Richard) \end{align*} \]

next replace ground atomic sentences, such as \(King(John)\), with proposition symbols, such as \(JoinIsKing\). Finally, apply any of the complete propositional algorithms to obtain conclusions such as \(JohnIsEvil\), which is equivalent to \(Evil(John)\).

Unification and Frist-Order Inference

Generalized Modus Ponens: For atomic sentences \(p_i, p_i'\) and \(q\), where there is a substitution \(\theta\) such that \(\text{SUBST}(\theta, p_i') = \text{SUBST}(\theta, p_i)\), for all \(i\),

\[ \frac{p_1', p_2', \dots, p_n', (p_1 \land p_2 \land \dots \land p_n \implies q)}{\text{SUBST}(\theta, q)} \]

For example

\[ \begin{array}{ll} p_1' = King(John) & p_1 = King(x) \\ p_2' = Greedy(y) & p_2 = Greedy(x) \\ \theta = \{ x/John, y/John\} & q = Evil(x) \\ \text{SUBST}(\theta, q) = Evil(John) \end{array} \]

Generalized Modus Ponens is a lifted version of Modus Ponens —— it raises Modus Ponens from ground (variable free) propositional logic to first-order logic. The key advantage of lifted inference rules over propositionalization is that they make only those substitutions that are required to allow particular inferences to proceed.

Unification

Lifted inference rules require finding substitutions that make different logical expressions look identical. This process is called unification and is a key component of all first-order inference algorithms. The \(\text{UNIFY}\) algorithm takes two sentences and returns a unifier for them.

\[ \text{UNIFY}(p, q) = \theta \text{ where } \text{SUBST}(\theta, p) = \text{SUBST}(\theta, q) \]

We said that \(\text{UNIFY}\) should return a substitution that makes the two arguments look the same. But there could be more than one such unifier. Every unifiable pair of expressions has a single most general unifier (MGU) that is unique up to renaming and substitution of variables.

The process of computing the most general unifiers is simple: recursively explore the two expressions simultaneously “side by side”, building up a unifier along the way, but failing if two corresponding points in the structures do not match.

// Unification Algorithm |

The arguments \(x\) and \(y\) can be any expression: a constant or variable, or a compound expression such as a complex sentence or term, or a list of expressions. The argument \(\theta\) is a substitution, initially the empty substitution, but with \(\{ var / val\}\) pairs added to it as we recurse through the inputs, comparing the expressions element by element. In a compound expression such as \(F(A, B)\), \(OP(x)\) field picks out the function symbol \(F\) and \(ARGS(x)\) field picks out the argument list \((A, B)\)

Storage and Retrieval

Underlying the \(\text{TELL}\), \(\text{ASK}\), and \(\text{ASKVARS}\) functions used to inform and interrogate a knowledge base are the more primitive \(\text{STORE}\) and \(\text{FETCH}\) functions. \(\text{STORE}(s)\) stores a sentence \(s\) into the knowledge base and \(\text{FETCH}(q)\) returns all unifiers such that the query \(q\) unifies with some sentence in the knowledge base.

Forward Chaining

Those logical sentences that cannot be stated as a definite clause cannot be handled by this approach.

First-Order Definite Clauses

First-order definite clauses are disjunctions of literals of which exactly one is positive. That means a definite clause is either atomic, or is an implication whose antecedent is a conjunction of positive literals and whose consequent is a single positive literal. Existential quantifiers are not allowed, and universal quantifiers are left implicit: if you see an x in a definite clause, that means there is an implicit \(\forall x\) **quantifier. For example

\[ King(x) \land Greedy(x) \implies Evil(x) \]

The literals \(King(John)\) and \(Greedy(y)\) is interpreted as “everyone is greedy” (the universal quantifier is implicit).

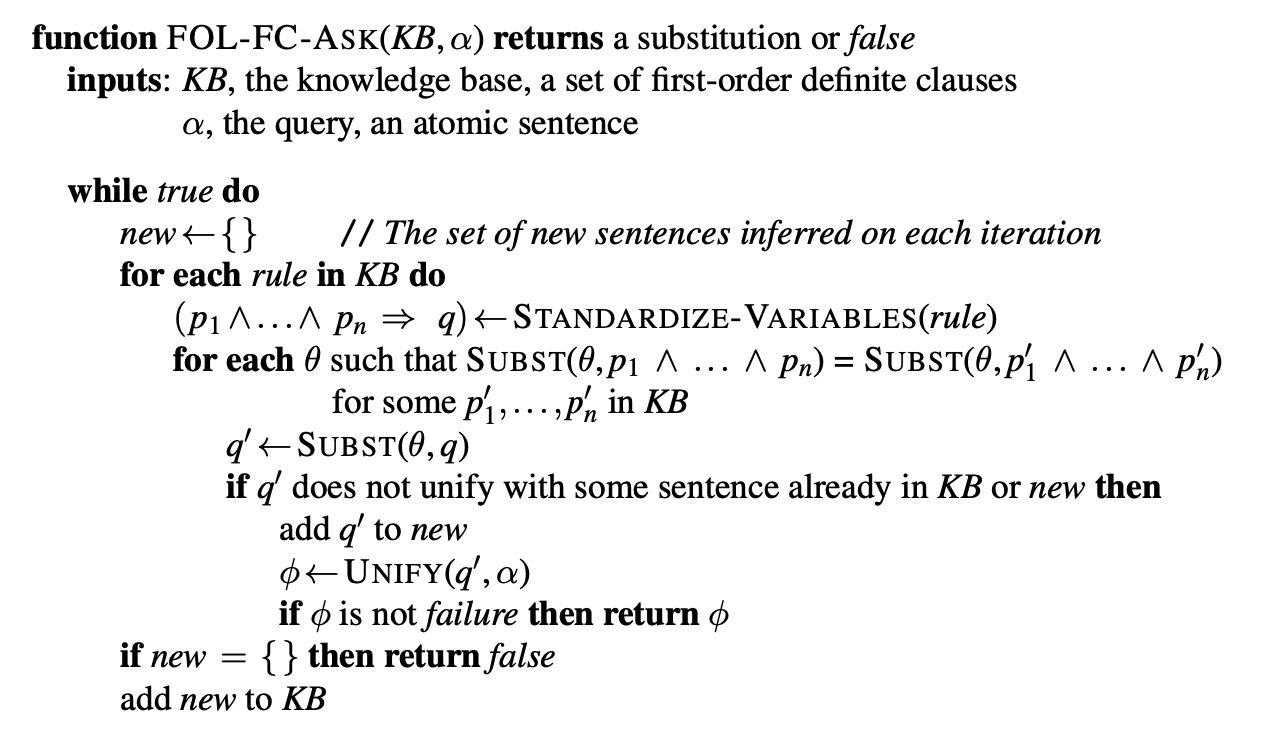

A Simple Forward-Chaining Algorithm

Starting from the known facts. The process repeats until the query is answered (assuming that just one answer is required) or no new facts are added.

On each iteration, it adds to KB all the atomic sentences that can be

inferred in one step from the implication sentences and the atomic

sentences already in KB. The function STANDARDIZE-VARIABLES

replaces all variables in its arguments with new ones that have not been

used before.

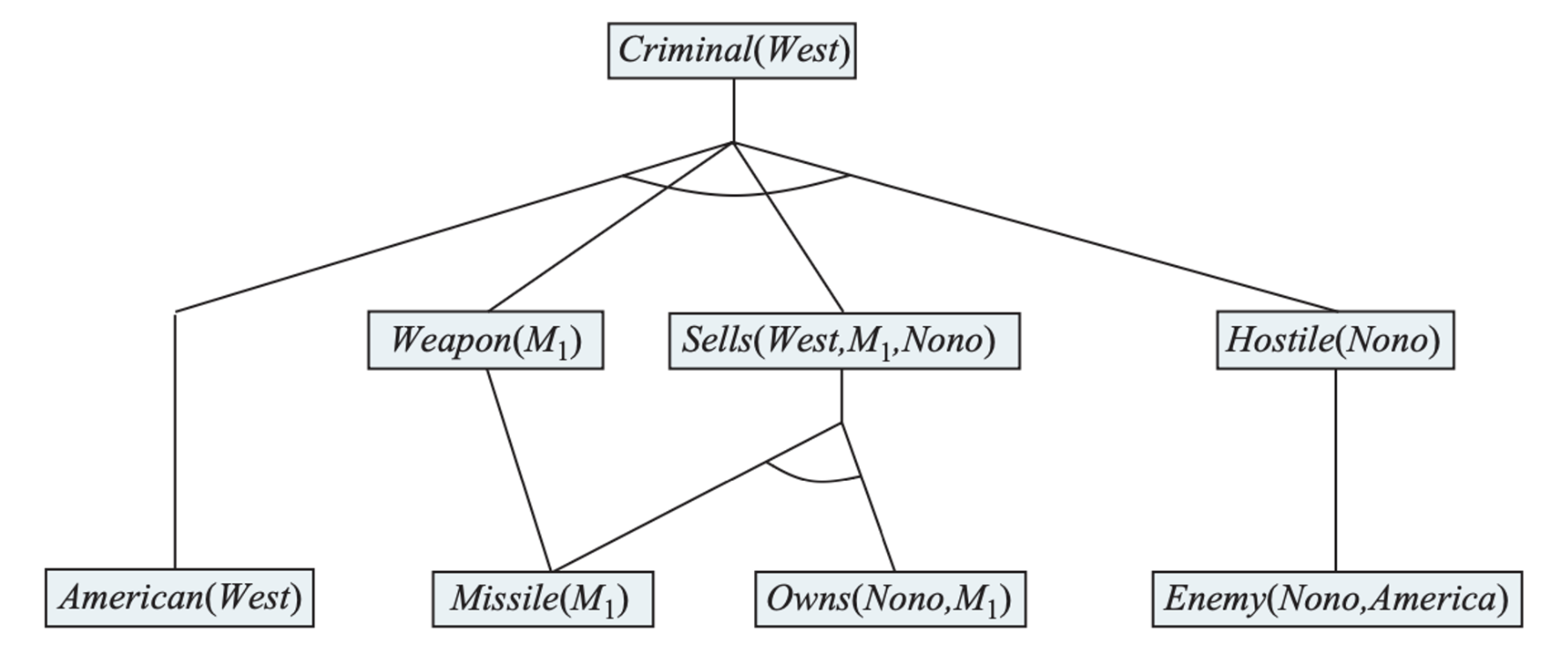

An example

Let us put definite clauses to work in representing the following problem:

The law says that it is a crime for an American to sell weapons to hostile nations. The country Nono, an enemy of America, has some missiles, and all of its missiles were sold to it by Colonel West, who is American.

\[ \begin{align} & \text{American}(x) \land \text{Weapon}(y) \land \text{Sells}(x, y,z ) \land \text{Hostile}(z) \implies \text{Criminal}(x) \\ & \text{Owns}(Nono, M_1) \\ & \text{Missle}(M_1) \\ & \text{Missle}(x) \land \text{Owns}(Nono, x) \implies \text{Sells}(West, x, Nono) \\ & \text{Missile}(x) \implies \text{Weapon}(x) \\ & \text{Enemy}(x, America) \implies \text{Hostile}(x) \\ & \text{American}(West) \\ & \text{Enemy}(Nono, America) \end{align} \\ \]

- On the first iteration, rule (1) has unsatisfied premises.

- Rule (4) is satisfied with \(\{x/M_1\}\), and \(\text{Sells}(West, M_1, Nono)\) is added.

- Rule (5) is satisfied with \(\{x/M_1\}\), and \(\text{Weapon}(M_1)\) is added.

- Rule (6) is satisfied with \(\{x/Nono\}\), and \(\text{Hostile}(Nono)\) is added.

- On the second iteration, rule (1) is satisfied with \(\{ x/West, y/M_1, z/Nono\}\), and the inference \(\text{Criminal}(West)\) is added.