First-Order Logic

First-order logic is also called first-order predicate calculus, it may be abbreviated as FOL or FOPC.

Representation Languages

What programming languages lack is a general mechanism for deriving facts from other facts; each update to a data structure is done by a domain-specific procedure whose details are derived by the programmer from his or her own knowledge of the domain. This procedural approach can be contrasted with the declarative nature of propositional logic, in which knowledge and inference are separate, and inference is entirely domain independent.

Propositional logic

- It is a declarative language because its semantics is based on a truth relation between sentences and possible worlds.

- It also has sufficient expressive power to deal with partial information, using disjunction and negation.

- It has a third property that is desirable in representation languages, namely, compositionality. In a compositional language, the meaning of a sentence is a function of the meaning of its parts.

However, propositional logic, as a factored representation, lacks the expressive power to concisely describe an environment with many objects.

Combining the Best of Formal and Natural Languages

When we look at the syntax of natural language, the most obvious elements are nouns and noun phrases that refer to objects and verbs and verb phrases along with adjectives and adverbs that refer to relations among objects. Some of these relations are functions —— relations in which there is only one “value” for a given “input”.

The primary difference between propositional and first-order logic lies in the ontological commitment made by each language —— that is, what it assumes about the nature of reality.

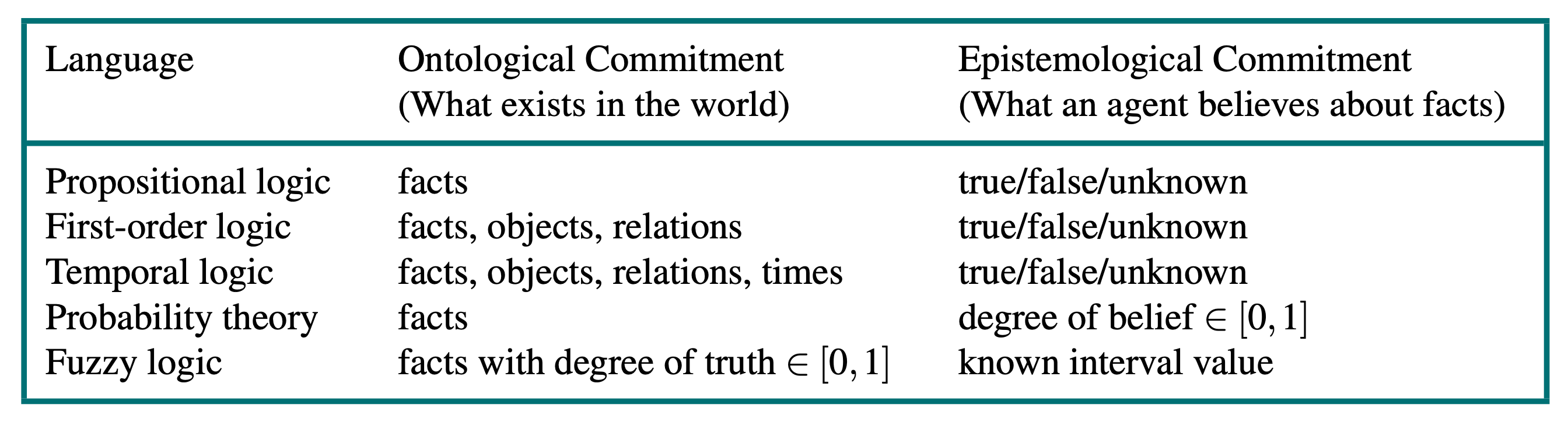

Formal languages and their ontological and epistemological commitments.

Various special-purpose logics make still further ontological commitments; for example, temporal logic assumes that facts hold at particular times and that those times are ordered. Higher-order logic views the relations and functions referred to by first-order logic as objects in themselves.

A logic can also be characterized by its epistemological commitments —— the possible states of knowledge that it allows with respect to each fact. In both propositional and first-order logic, a sentence represents a fact and the agent either believes the sentence to be true, believes it to be false, or has no opinion. These logics therefore have three possible states of knowledge regarding any sentence.

Systems using probability theory, can have any degree of belief, or subjective likelihood, ranging from 0 (total disbelief) to 1 (total belief).

Syntax and Semantics of First-Order Logic

Models for First-Order Logic

In propositional logic, models link proposition symbols to predefined truth values. In first-order logic, the domain of a model is the set of objects or domain elements it contains. The domain is required to be nonempty —— every possible world must contain at least one object.

The objects in the model may be related in various ways. A relation is just the set of tuples of objects that are related.

Strictly speaking, models in first-order logic require total functions, that is, there must be a value for every input tuple.

Symbols and Interpretations

The basic syntactic elements of first-order logic are the symbols that stand for objects, relations, and functions. The symbols, therefore, come in three kinds: constant symbols, which stand for objects; predicate symbols, which stand for relations; and function symbols, which stand for functions.

\[ \begin{align} \text{Sentence} &\to \text{AtomicSentence} \ |\ \text{ComplexSentence} \\ \text{AtomicSentence} &\to \text{Predicate} \ |\ \text{Predicate(Term, ...)} \ |\ \text{Term} = \text{Term} \\ \text{ComplexSentence} &\to (\text{Sentence}) \\ &\ \ \ | \ \neg \text{Sentence} \\ &\ \ \ | \ \text{Sentence} \land \text{Sentence} \\ &\ \ \ | \ \text{Sentence} \lor \text{Sentence} \\ &\ \ \ | \ \text{Sentence} \implies \text{Sentence} \\ &\ \ \ | \ \text{Sentence} \iff \text{Sentence} \\ &\ \ \ | \ \text{Quantifier} \ \text{Variable}, \dots \text{Sentence} \\ \text{Term} &\to \text{Function}(\text{Term}, \dots) \\ &\ \ \ | \ \text{Constant} \\ &\ \ \ | \ \text{Variable} \\ \text{Quantifier} &\to \forall \ |\ \exists \\ \text{Constant} &\to A \ |\ X_1 \ |\ John \ |\ \cdots \\ \text{Variable} &\to a \ |\ x \ |\ s \ |\ \cdots \\ \text{Predicate} &\to True \ |\ False \ |\ After \ |\ Loves \ | \cdots \\ \text{Function} &\to Mother \ |\ LeftLeg \ | \cdots \\ \text{Operator Precedence} &\to \neg, =, \land, \lor, \implies, \iff \end{align} \]

The syntax of first-order logic with equality, specified in Backus–Naur form. Operator precedences are specified, from highest to lowest. The precedence of quantifiers is such that a quantifier holds over everything to the right of it.

Every model must provide the information required to determine if any given sentence is true or false. Thus, in addition to its objects, relations, and functions, each model includes an interpretation that specifies exactly which objects, relations and functions are referred to by the constant, predicate, and function symbols.

Terms

A term is a logical expression that refers to an object. In the general case, a complex term is formed by a function symbol followed by a parenthesized list of terms as arguments to the function symbol.

In a term \(f(t_1, \cdots, t_n)\), the function symbol \(f\) refers to some function in the model (call it \(F\)); the argument terms refer to objects in the domain (call them \(d_1, \cdots, d_n\)); and the term as a whole refers to the object that is the value of the function \(F\) applied to \(d_1, \cdots, d_n\).

Atomic Sentences

An atomic sentence is formed from a predicate symbol optionally followed by a parenthesized list of terms, such as

\[ Brother(Richard, John) \]

Atomic sentences can have complex terms as arguments

\[ Married(Father(Richard), Mother(John)) \]

An atomic sentence is true in a given model if the relation referred to by the predicate symbol holds among the objects referred to by the arguments.

Complex Sentences

Logical connectives are used to construct more complex sentences.

\[ \begin{align*} &\neg Brother(LeftLeg(Richard), John) \\ & Brother(Richard, John) \land Brother(John, Richard) \end{align*} \]

Quantifiers

Universal quantifier \(\forall\) and existential quantifier \(\exists\).

Universal Quantifier

The sentence \(\forall x P\), where \(P\) is any logical sentence, say that \(P\) is true for every object \(x\). More precisely, \(\forall x P\) is true in a given model if \(P\) is true in all possible extended interpretations constructed from the interpretation given in the model, where each extended interpretation specifies a domain element to which \(x\) refers.

By asserting the universally quantified sentence, which is equivalent to asserting a whole list of individual implications, we end up asserting the conclusion of the rule just for those objects for which the premise is true and saying nothing at all about those objects for which the premise is false. Thus, the truth-table definition of \(\implies\) turns out to be perfect for writing general rules with universal quantifiers.

Existential Quantification

The sentence \(\exists x P\) says that \(P\) is true for at least one object \(x\). More precisely, \(\exists x P\) is true in a given model if \(P\) is true in at least one extended interpretation that assigns \(x\) **to a domain element.

Just as \(\implies\) appears to be the natural connective to use with \(\forall\), \(\land\) is the natural connective to use with \(\exists\).

Nested Quantifiers

Some examples

\[ \begin{align*} & \forall x, \forall y \ Brother(x, y) \implies Sibling(x, y) \\ & \forall x \exists y \ Loves(x, y) \\ & \exists y \forall x \ Loves(x, y) \\ & \forall x \ (Crown(x) \lor (\exists x \ Brother(Richard, x))) \end{align*} \]

Connections between Universal and Existential Quantifier

The two quantifiers are actually intimately connected with each other, through negation. The De Morgan rules for quantified and unquantified sentences are as follows:

\[ \begin{align*} & \neg \exists x \ P \equiv \forall x \ \neg P &\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \neg(P \lor Q) \equiv \neg P \land \neg Q \\ & \neg \forall x \ P \equiv \exists x \ \neg P & \neg(P \land Q) \equiv \neg P \lor \neg Q \\ & \forall x \ P \equiv \neg \exists x \ \neg P & P \land Q \equiv \neg(\neg P \lor \neg Q) \\ & \exists x \ P \equiv \neg \forall x \ \neg P & P \lor Q \equiv \neg(\neg P \land \neg Q) \\ \end{align*} \]

Equality

Equality symbol is used to signify that two terms refer to the same object. For example

\[ Father(John) = Henry \]

Database Semantics

In a database system, we insist that every constant symbol refer to a distinct object —— the unique-names assumption. Second, we assume that atomic sentences not known to be true are in fact false —— the closed world assumption. Finally, we invoke domain closure, meaning that each model contains no more domain elements than those named by the constant symbols.

Using First-Order Logic

In knowledge representation, a domain is just some part of the world about which we wish to express some knowledge.

Assertions and Queries in Fisrt-Order Logic

Sentences are added to a knowledge base using TELL. Such

sentences are called assertions. Questions asked with

ASK are called queries or

goals. Geerally speaking, any query that is logically

entailed by the knowledge base should be answered affirmatively.

For example

\[ \begin{align*} & \text{TELL}(KB, \text{King}(John)) \\ & \text{TELL}(KB, \text{Person}(Richard)) \\ & \text{TELL}(KB, \forall x \ \text{King}(x) \implies \text{Person}(x)) \\ \\ & \text{ASK}(KB, \text{Person}(John)) \to true \end{align*} \]

If we want to know what value of \(x\) makes the sentence true, we will need a

different function, which we call ASKVARS.

\[ \text{ASKVARS}(KB, \text{Person}(x)) \to \{x/John\}, \{x/Richard\} \]

Such an answer is called a substitution or binding list.

The Kinship Domain

Kinship relations are represented by binary predicates: Parent, Sibling, Brother, Sister, Child, Daughter, Son, Spouse, Wife, Husband, Grandparent, Grandchild, Cousin, Aunt, and Uncle. We can go through each function and predicate, writing down what we know in terms of the other symbols.

\[ \begin{align*} & \forall m,c \ \text{Mother}(c) = m \iff \text{Female}(m) \land \text{Parent}(m, c) \\ & \forall w, h \ \text{Husband}(h, w) \iff \text{Male}(h) \land \text{Spouse}(h, w) \\ & \forall p, c \ \text{Parent}(p, c) \iff \text{Child}(c, p) \end{align*} \]

Each of these sentences can be viewed as an axiom of the kinship domain. The kinship axioms are also definitions; they have the form \(\forall x, y \ P(x, y) \iff \cdots\). Not all logical sentences about a domain are axioms. Some are theorems —— that is, they are entailed by the axioms.

Numbers

Peano axioms define natural numbers and addition. Natural numbers are defined recursively.

\[ \begin{align} & \text{NaturalNumber}(0) \\ & \forall n \ \text{NaturalNumber}(n) \implies \text{NaturalNumber}(S(n)) \end{align} \]

The successor function is constrained by

\[ \begin{align*} & \forall n \ 0 \neq S(n) \\ & \forall m, n \ m \neq n \implies S(m) \neq S(n) \end{align*} \]

Addition can be defined in terms of the successor function

\[ \begin{align*} & \forall m \ \text{NaturalNumber}(m) \implies +(0, m) = m \\ & \forall m, n \ \text{NaturalNumber}(m) \land \text{NaturalNumber}(n) \implies +(S(m), n) = S(+(m, n)) \end{align*} \]

Once we have addition, it is straightforward to define multiplication as repeated addition, exponentiation as repeated multiplication, integer division and remainders, prime numbers and so on. Thus the whole number theory can be built up from one constant, one function, one predicate and four axioms.

Sets

Define an operation \(\text{Add}(x, s)\), which gives the set resulting from adding element \(x\) to set \(s\). One possible set of axioms is as follows:

The only sets are the empty set and those made by adding something to a set:

\[ \forall s \ \text{Set}(s) \iff (s = \{\}) \lor (\exists x, s_2 \ \text{Set}(s_2) \land (s = \text{Add}(x, s_2))) \]

The empty set has no elements added into it. There is no way to decompose \(\{\}\) into a smaller set and an element:

\[ \neg \exists x, s \ \text{Add}(x, s) = \{\} \]

Adding an element already in the set has no effect:

\[ \forall x, s \ x \in s \iff s = \text{Add}(x, s) \]

The only members of a set are the elements that were added into it.

\[ \forall x, s \ x \in s \iff \exists y, s_2 \ (s = \text{Add}(y, s_2)) \land (x = y \lor x \in s_2) \]

A set is a subset of another set if and only if all of the first set’s members are members of the second set:

\[ \forall s_1, s_2 \ s_1 \subseteq s_2 \iff (\forall x \ x \in s_1 \implies x \in s_2) \]

Two sets are equal if and only if each is a subset of the other:

\[ \forall s_1, s_2 \ (s_1 = s_2) \iff (s_1 \subset s_2 \land s_2 \subset s_1) \]

An object is in the intersection of two sets if and only if it is a member of both sets:

\[ \forall x, s_1, s_2 \ x \in (s_1 \cap s_2) \iff (x \in s_1 \land x \in s_2) \]

An object is in the union of two sets if and only if it is a member of either set:

\[ \forall x, s_1, s_2 \ x \in (s_1 \cup s_2) \iff (x \in s_1 \lor x \in s_2) \]

The Wumpus World

A typical percept sentence would be

\[ \text{Percept}([Stench, Breeze, Clitter, None, None], 5) \]

The integer is time step.

The actions in the wumpus world can be represented by logical terms:

\[ \text{Turn}(Right), \text{Turn}(Left), \text{Forward}, \text{Shoot}, \text{Grab}, \text{Climb} \]

Knowledge Engineering in First-Order Logic

A knowledge engineer is someone who investigates a particular domain, learns what concepts are important in that domain, and creates a formal representation of the objects and relations in the domain.

The Knowledge Engineering Process

1. Identify the questions

The knowledge engineer must delineate the range of questions that the knowledge base will support and the kinds of facts that will be available for each specific problem instance.

2. Assemble the relevant knowledge

A process called knowledge acquisition. At this stage, the knowledge is not represented formally. The idea is to understand the scope of the knowledge base, as determined by the task, and to understand how the domain actually works.

3. Decide on a vocabulary of predicates, functions, and constants

Translate the important domain-level concepts into logic-level names. Once the choices have been made, the result is a vocabulary that is known as the ontology of the domain. The word ontology means a particular theory of the nature of being or existence. The ontology determines what kinds of things exist, but does not determine their specific properties and interrelationships.

4. Encode general knowledge about the domain

The knowledge engineer writes down the axioms for all the vocabulary terms.

5. Encode a description of the problem instance

It involves writing simple atomic sentences about instances of concepts that are already part of the ontology.

6. Pose queries to the inference procedure and get answers

We can let the inference procedure operate on the axioms and problem-specific facts to derive the facts we are interested in knowing.

7. Debug and evaluate the knowledge base

Summary

- Knowledge representation languages should be declarative, compositional, expressive, context independent, and unambiguous.

- Logics differ in their ontological commitments and epistemological commitments. While propositional logic commits only to the existence of facts, first-order logic commits to the existence of objects and relations and thereby gains expressive power, appropriate for domains such as the wumpus world and electronic circuits.

- Both propositional logic and first-order logic share a difficulty in representing vague propositions. This difficulty limits their applicability in domains that require personal judgments, like politics or cuisine.

- The syntax of first-order logic builds on that of propositional logic. It adds terms to represent objects, and has universal and existential quantifiers to construct assertions about all or some of the possible values of the quantified variables.

- A possible world, or model, for first-order logic includes a set of objects and an interpretation that maps constant symbols to objects, predicate symbols to relations among objects, and function symbols to functions on objects.

- An atomic sentence is true only when the relation named by the predicate holds between the objects named by the terms. Extended interpretations, which map quantifier variables to objects in the model, define the truth of quantified sentences.

- Developing a knowledge base in first-order logic requires a careful process of analyzing the domain, choosing a vocabulary, and encoding the axioms required to support the desired inferences.