Intelligent Agents

Agents and Environments

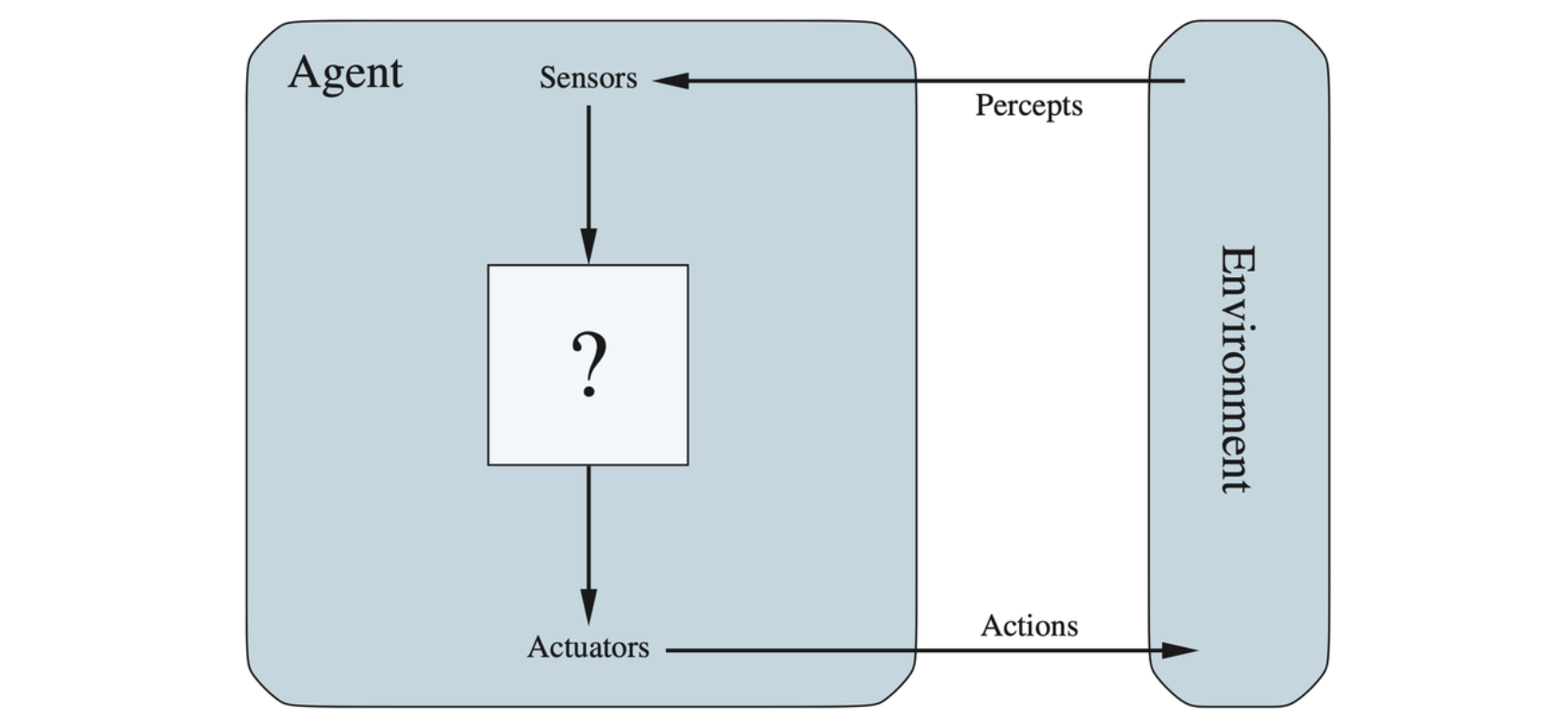

An agent is anything that can be viewed as perceiving its environment through sensors and acting upon that environment through actuators.

Agents interact with environments through sensors and actuators

The term percept is used to refer to the content an agent’s sensors are perceiving. An agent’s percept sequence is the complete history of everything the agent has ever perceived. In general, an agent’s choice of action at any given instant can depend on its built-in knowledge and on the entire percept sequance observed to date, but not on anything it hasn’t perceived.

An agent’s behavior is described by the agent function that maps any given percept sequence to an action. Internally, the agent function for an artificial agent will be implemented by an agent program. The agent function is an abstract mathematical description; the agent program is a concrete implementation, running within some physical system.

The Concept of Rationality

A rational agent is one that does the right thing.

Performance Measures

An agent’s behavior is evaluated by its consequences, which is called consequentialism.

When an agent is plunked down in an environment, it generates a sequence of actions according to the percepts it receives. This sequence of actions causes the environment to go through a sequence of states. If the sequence is desirable, then the agent has performed well. This notion of desirability is captured by a performance measure that evaluates any given sequence of environment states.

Rationality

Definition of a rational agent: For each possible percept sequence, a rational agent should select an action that is expected to maximize its performance measure, given the evidence provided by the percept sequence and whatever built-in knowledge the agent has.

Omniscience, Learning and Autonomy

Rationality maximizes expected performance, while perfection maximizes actual performance. The definition of rationality does not require omniscience, then, because the rational choice depends only on the percept sequence to date.

Doing actions in order to modify future percepts —— sometimes called information gethering —— is an important part of rationality. A rational agent should not only to gather information but also to learn as much as possible from what it perceives.

A rational agent should be autonomous —— it should learn what it can to compensate for partial or incorrect prior knowledge.

The Nature of Environment

Task environments, which are essentially the “problems” to which rational agents are the “solutions”.

Specifying the Task Environment

In the discussion of the rationality of the agents, we had to specify the performance measure, the environment, and the agent’s actuators and sensors. These are grouped in the description of a task environment. For acronymically minded, these are called PEAS (Performance, Environment, Actuator, Sensors).

| Agent Type | Performance Measure | Environment | Actuators | Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxi driver | Safe, fast, legal, comfortable trip, maximize profits, minimize impact on other road users | Roads, other traffic, police, pedestrians, customers, weather | Steering, accelerator, brake, signal, horn, display, speech | Cameras, radar, speedometer, GPS, engine sensors, accelerometer, microphones, touchscreen |

PEAS description of the task environment for an automated taxi driver.

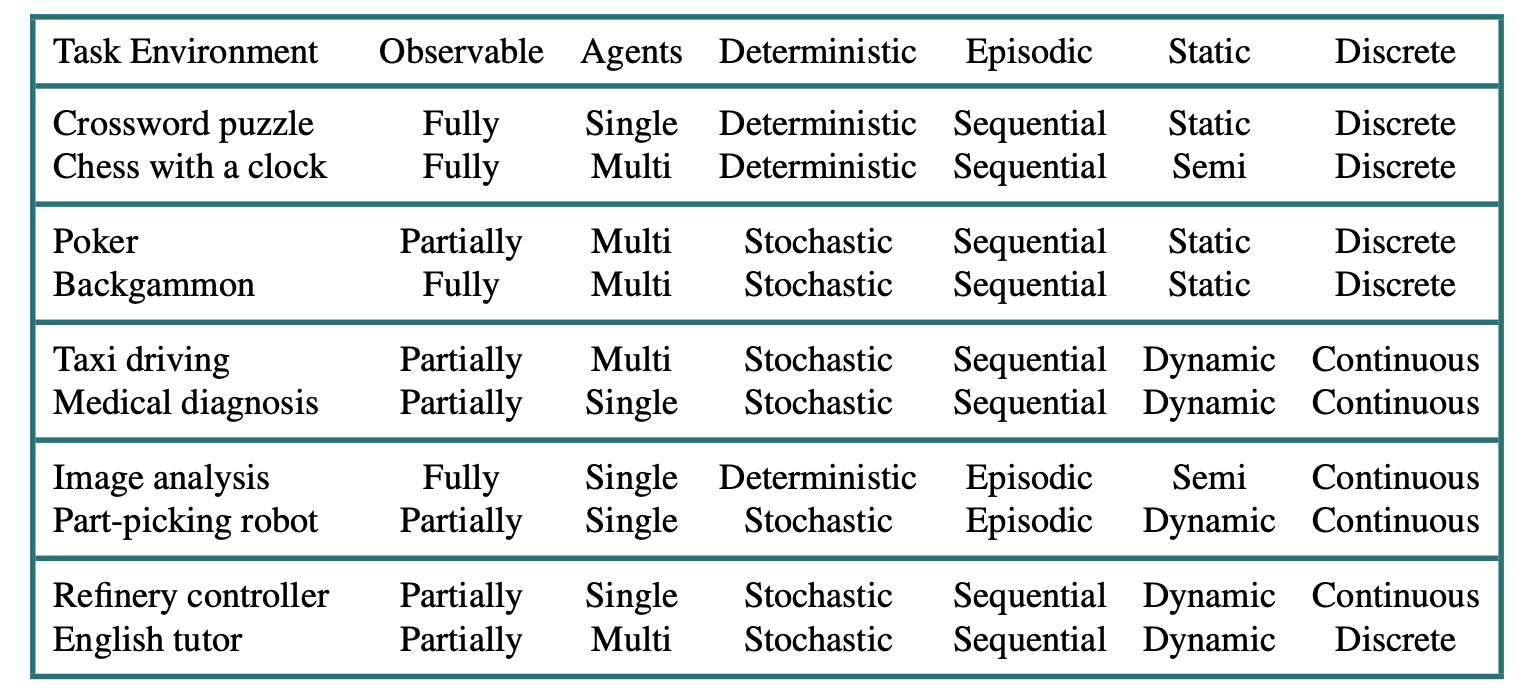

Properties of Task Environment

- Fully observable vs. partially observable: Whether an agent’s sensors give it access to the complete state of the environment at each point in time.

- Single-agent vs. multiagent: Chess is a competitive multiagent environment. Auto-driving is a partially cooperative multiagent environment.

- Deterministic vs. nondeterministic: Whether the next state of the environment is completely determined by the current state and the action executed by the agents.

- Episodic vs. sequential: Whether the agent’s experience is divided into atomic episodes. In sequential environments, the current decision could affect all future decisions.

- Static vs. dynamic: Whether the environment can change while an agent is deliberating.

- Discrete vs. continuous: The discrete/continuous distinction applies to the state of the environment, to the way time is handled, and to the percepts and actions of the agent.

- Known vs. unknown: whether the outcomes for all actions are given.

The hardest case is partially observable, multiagent, nondeterministic, sequential, dynamic, continuous, and unknown. Taxi driving is hard in all these scenes.

Examples of task environments and their characteristics.

The Structure of Agents

The job of AI is to design an agent program that implements the agent function —— the mapping from percepts to actions. The program is assumed to run on some sort of computing device with physical sensors and actuators —— which is called agent architecture.

\[ agent = architecture + program \]

Agent Programs

The agent programs that we designed in this book all have the same skeleton: they take the current percept as input from the sensors and return an action to the actuators.

// The TABLE-DRIVEN-AGENT program |

The key challenge for AI is to find out how to write programs that, to the extent possible, produce rational behavior from a smallish program rather than from a vast table.

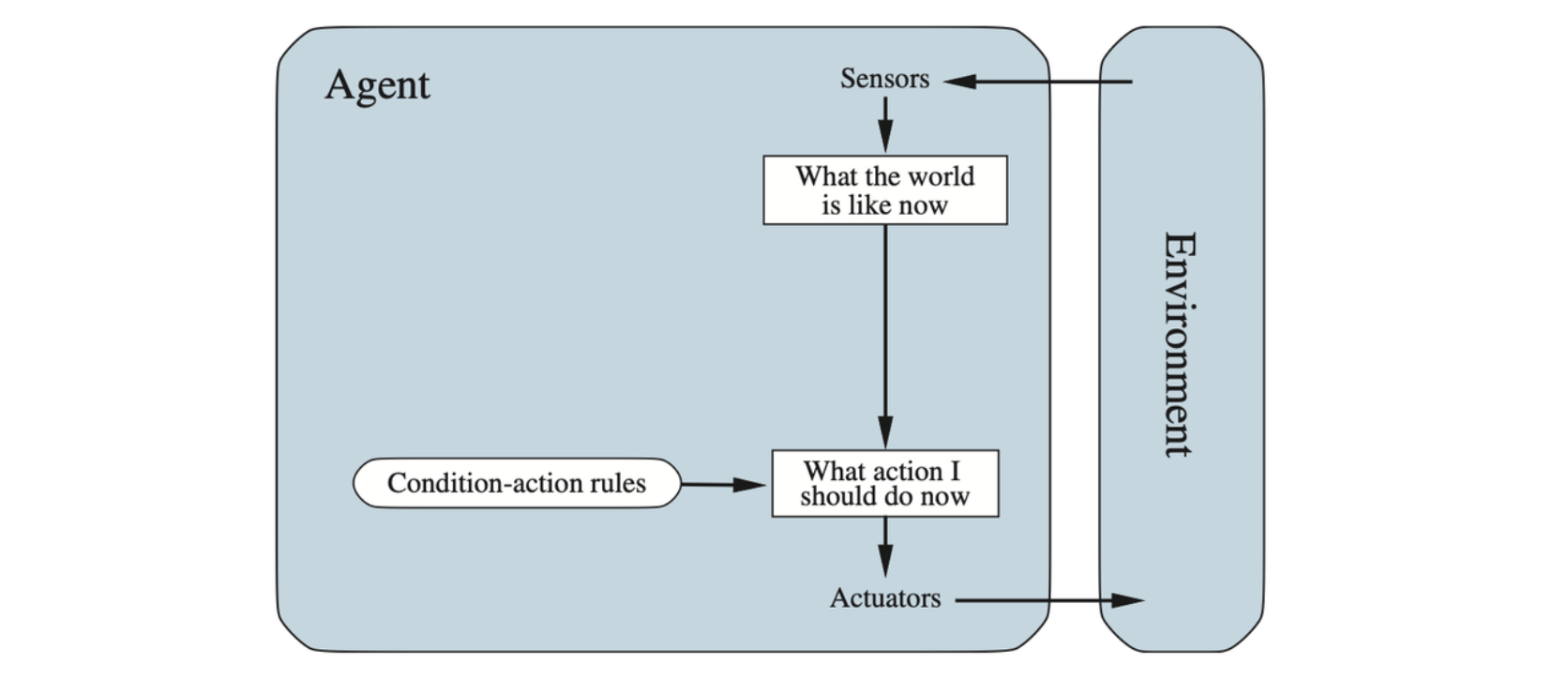

Simple Reflex Agents

These agents select actions on the basis of the current percept, ignoring the rest of the percept history.

Schematic diagram of a simple reflex agent. We use rectangles to denote the current internal state of the agent’s decision process, and ovals to represent the background information used in the process.

// A Simple Reflex Agent |

Sometimes a randomized simple reflex agent might outperform a deterministic simple reflex agent.

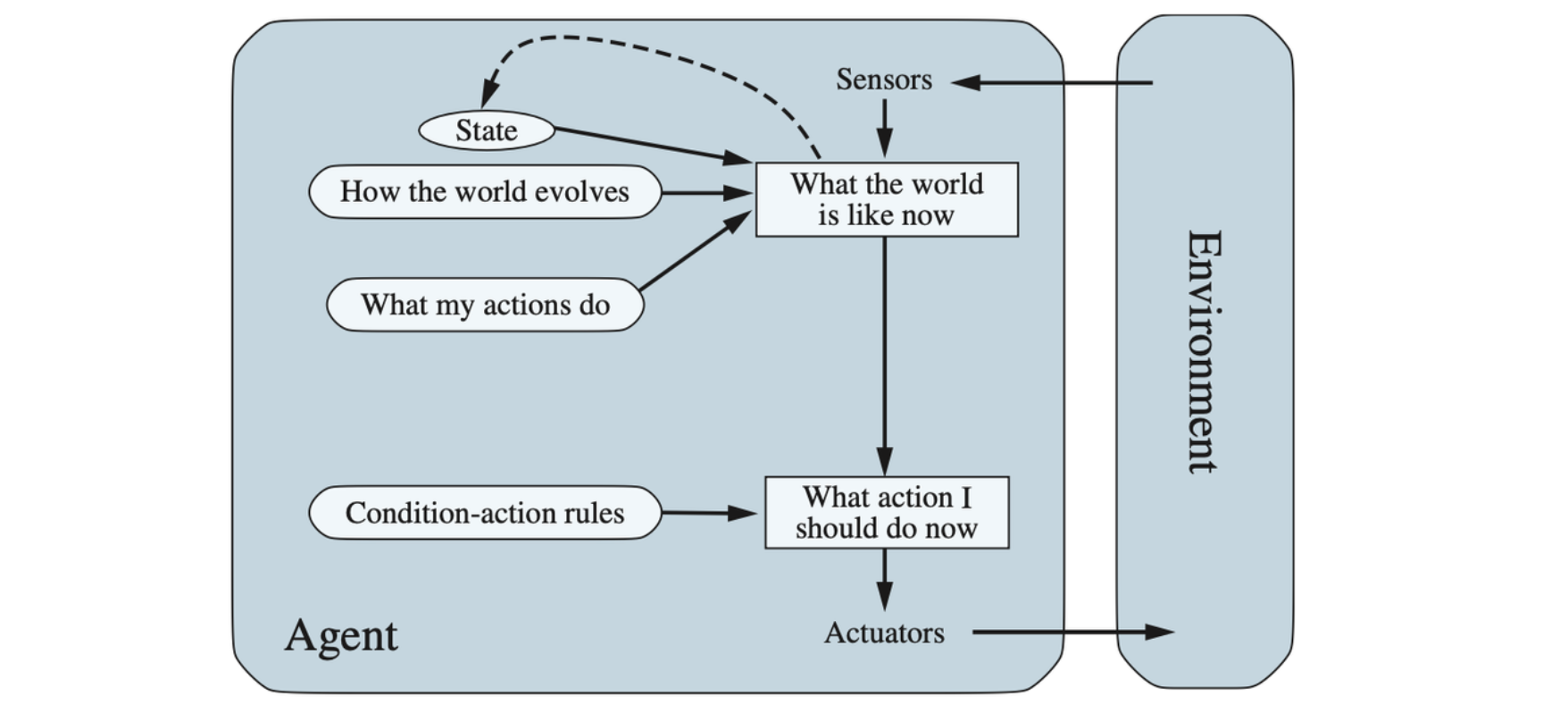

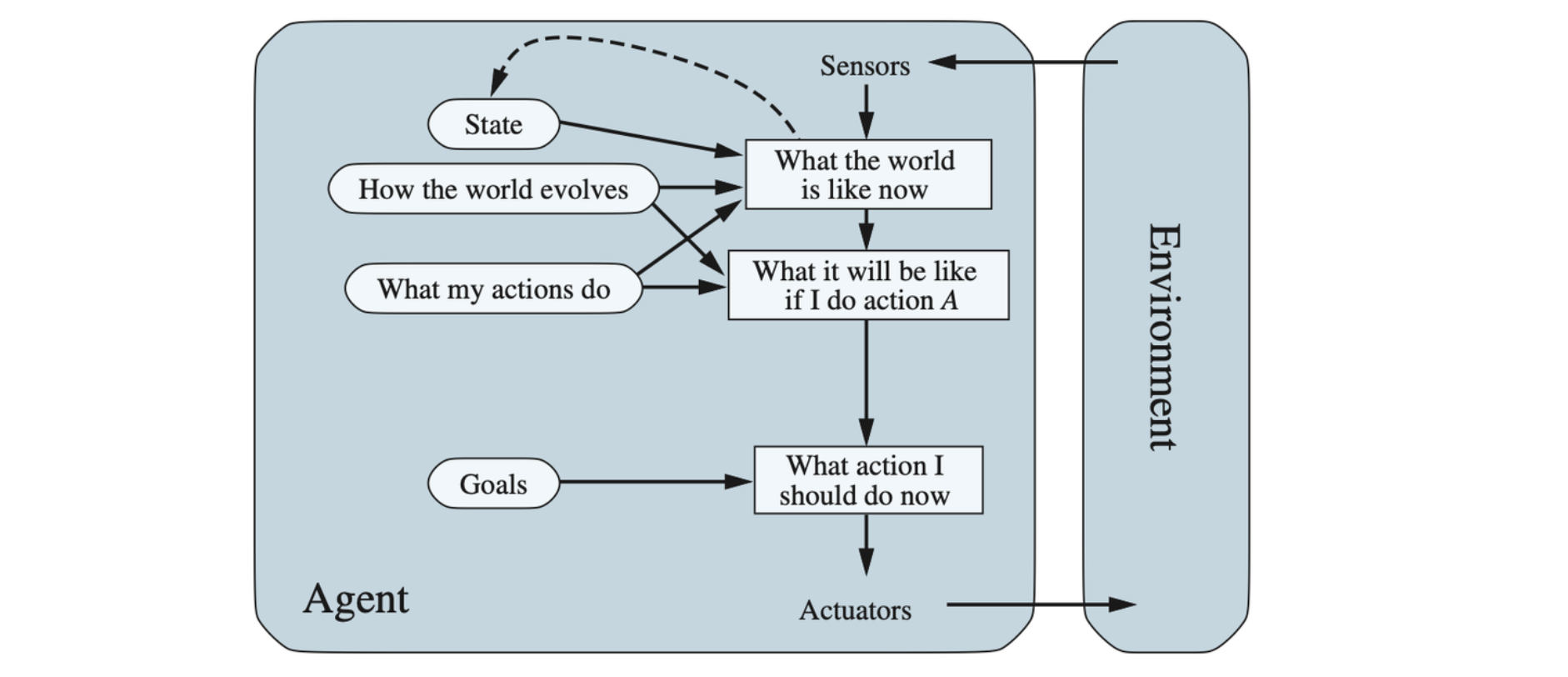

Model-based Reflex Agents

The most effective way to handle partial observability is for the agent to keep track of the part of the world it can’t see now. That is, the agent should maintain some sort of internal state that depends on the percept history and thereby reflects at least some of the unobserved aspects of the current state.

A model-based reflex agent.

// A Model-Based Reflex Agent |

Goal-Based Agents

As well as a current state description, the agent needs some sort of goal information that describes situations that are desirable. Search and planning are the subfields of AI devoted to finding action sequences that achieve the agent’s goals.

Although the goal-based agent appears less efficient, it is more flexible because the knowledge that supports its decisions is represented explicitly and can be modified.

A model-based, goal-based agent. It keeps track of the world state as well as a set of goals it is trying to achieve, and chooses an action that will (eventually) lead to the achievement of its goals.

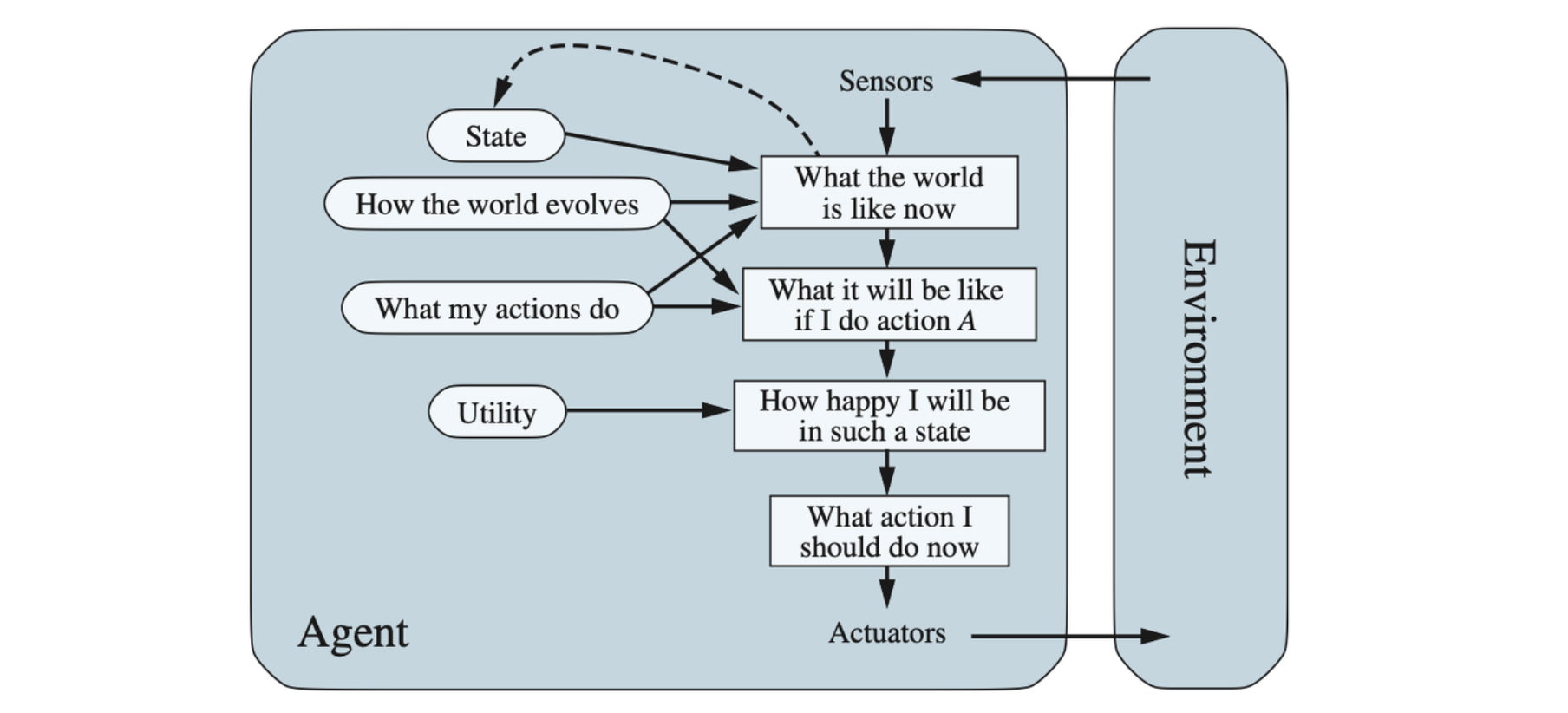

Utility-Based Agents

Goals just provide a crude binary distinction between “happy” and “unhappy” states. A more general performance measure should allow a comparison of different world states according to the quality of being useful. An agent’s utility function is essentially an internalization of the performance measure. Provided that the internal utility function and the external performance measure are in agreement, an agent that chooses actions to maximize its utility will be rational according to the external performance measure.

A model-based, utility-based agent. It uses a model of the world, along with a utility function that measures its preferences among states of the world. Then it chooses the action that leads to the best expected utility, where expected utility is computed by averaging over all possible outcome states, weighted by the probability of the outcome.

Partial observability and nondeterminism are ubiquitous in the real world, and so, there- fore, is decision making under uncertainty. Technically speaking, a rational utility-based agent chooses the action that maximizes the expected utility of the action outcomes—that is, the utility the agent expects to derive, on average, given the probabilities and utilities of each outcome.

A utility-based agent has to model and keep track of its environment, tasks that have involved a great deal of research on perception, representation, reasoning, and learning. Choosing the utility-maximizing course of action is also a difficult task, requiring ingenious algorithms.

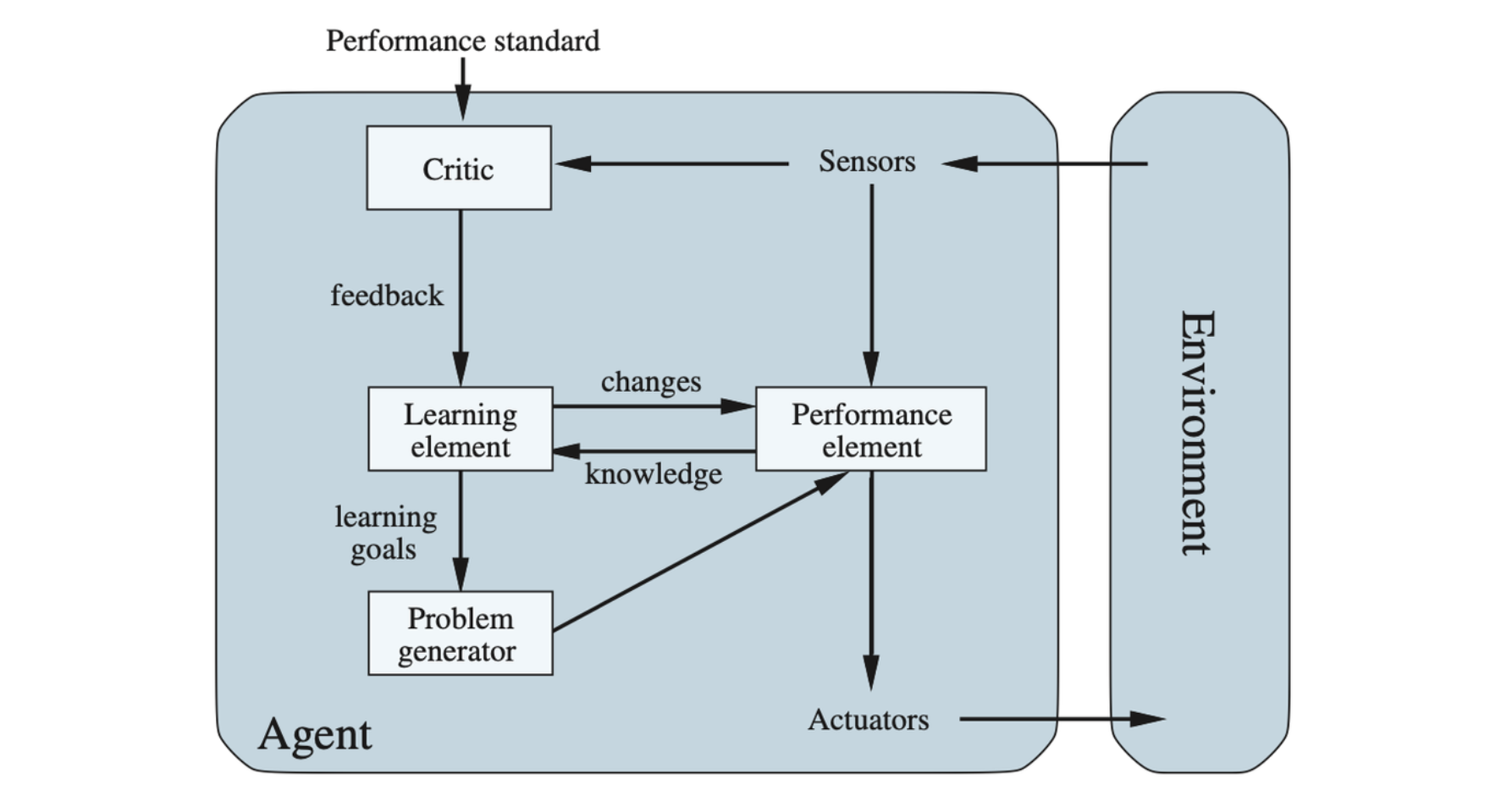

Learning Agents

A learning agent can be divided into four conceptual components. The most important distinction is between the learning element, which is responsible for making improvements, and the performance element, which is responsible for selecting external actions. The performance element is what has been previously considered to be the entire agent: it takes in percepts and decides on actions. The learning element uses feedback from the critic on how the agent is doing and determines how the performance element should be modified to do better in the future.

A general learning agent. The “performance element” box represents what we have previously considered to be the whole agent program. Now, the “learning element” box gets to modify that program to improve its performance.

The critic tells the learning element how well the agent is doing with respect to a fixed performance standard. The problem generator is responsible for suggesting actions that will lead to new and informative experiences.

How the Components of Agent Program Work

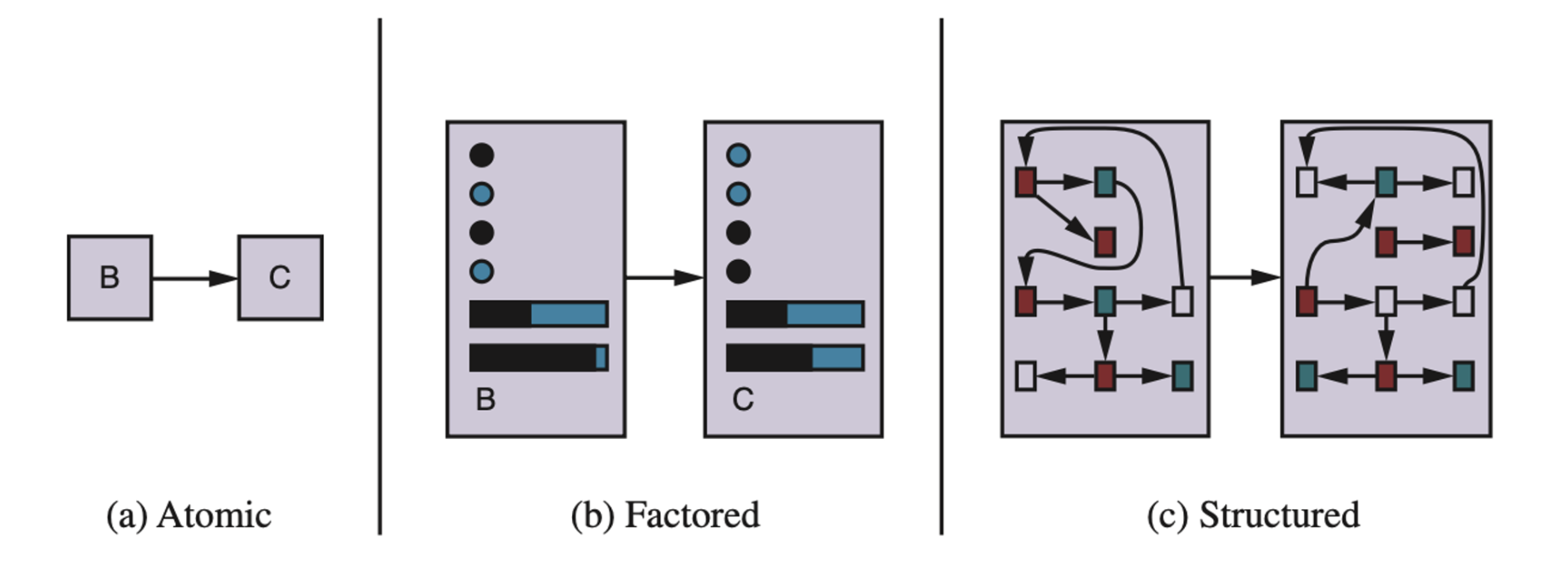

Roughly speaking, we can place the representations along an axis of increasing complexity and expressive power —— atomic, factored, and structured.

Three ways to represent states and the transitions between them.

Atomic representation: a state (such as B or C) is a black box with no internal structure;

Factored representation: a state consists of a vector of attribute values; values can be Boolean, real- valued, or one of a fixed set of symbols.

Structured representation: a state includes objects, each of which may have attributes of its own as well as relationships to other objects.

Summary

- An agent is something that perceives and acts in an environment. The agent function for an agent specifies the action taken by the agent in response to any percept sequence.

- The performance measure evaluates the behavior of the agent in an environment. A rational agent acts so as to maximize the expected value of the performance measure, given the percept sequence it has seen so far.

- A task environment specification includes the performance measure, the external environment, the actuators, and the sensors. In designing an agent, the first step must always be to specify the task environment as fully as possible.

- Task environments vary along several significant dimensions. They can be fully or partially observable, single-agent or multiagent, deterministic or nondeterministic, episodic or sequential, static or dynamic, discrete or continuous, and known or unknown.

- In cases where the performance measure is unknown or hard to specify correctly, there is a significant risk of the agent optimizing the wrong objective. In such cases the agent design should reflect uncertainty about the true objective.

- The agent program implements the agent function. There exists a variety of basic agent program designs reflecting the kind of information made explicit and used in the decision process. The designs vary in efficiency, compactness, and flexibility. The appropriate design of the agent program depends on the nature of the environment.

- Simple reflex agents respond directly to percepts, whereas model-based reflex agents maintain internal state to track aspects of the world that are not evident in the current percept. Goal-based agents act to achieve their goals, and utility-based agents try to maximize their own expected “happiness.”

- All agents can improve their performance through learning.