A Math and Geometry Primer

Matrices

Algebraic Identites involving matrices are listed below. Given scalars \(r\) and \(s\) and matrices \(\textbf{A}, \textbf{B}\) and \(\textbf{C}\). For matrix addition, subtraction and scalar multiplication:

\[ \begin{align} \textbf{A} + \textbf{B} &= \textbf{B} + \textbf{A} \\ \textbf{A} - \textbf{B} &= \textbf{A} + (-\textbf{B}) \\ -(-\textbf{A}) &= \textbf{A} \\ s(\textbf{A} \pm \textbf{B}) &= s\textbf{A} \pm s\textbf{B} \\ (r \pm s)\textbf{A} &= r\textbf{A} \pm s\textbf{A} \\ r(s\textbf{A}) &= s(r\textbf{A}) = (rs)\textbf{A} \end{align} \]

For matrix multiplication, the following identities hold:

\[ \begin{align} \textbf{A}\textbf{I} &= \textbf{I}\textbf{A} = \textbf{A} \\ \textbf{A}(\textbf{B}\textbf{C}) &= (\textbf{A}\textbf{B})\textbf{C} \\ \textbf{A}(\textbf{B} \pm \textbf{C}) &= \textbf{A}\textbf{B} \pm \textbf{A}\textbf{C} \\ (\textbf{A} \pm \textbf{B})\textbf{C} &= \textbf{A}\textbf{C} \pm \textbf{B}\textbf{C} \\ (s\textbf{A})\textbf{B} &= s(\textbf{A}\textbf{B}) = \textbf{A}(s\textbf{B}) \end{align} \]

For matrix transpose the following identities hold:

\[ \begin{align} (\textbf{A} \pm \textbf{B})^T &= \textbf{A}^T \pm \textbf{B}^T \\ (s\textbf{A})^T &= s\textbf{A}^T \\ (\textbf{A}\textbf{B})^T &= \textbf{B}^T\textbf{A}^T \end{align} \]

Determinants

The determinant of a matrix \(\textbf{A}\) is a number associated with \(\textbf{A}\), denoted \(\det(\textbf{A})\) or \(|\textbf{A}|\). It is often used in determining the solvability of systems of linear equations.

\[ \begin{align} |\textbf{A}| &= |u_1| = u_1 \\ |\textbf{A}| &= \begin{vmatrix} u_1 & u_2 \\ v_1 & v_2 \end{vmatrix} = u_1 v_2 - u_2 v_1 \\ |\textbf{A}| &= \begin{vmatrix} u_1 & u_2 & u_3 \\ v_1 & v_2 & v_3 \\ w_1 & w_2 & w_3 \end{vmatrix} \\ &= u_1(v_2 w_3 - v_3 w_2) + u_2(v_3 w_1 - v_1 w_3) + u_3(v_1 w_2 - v_2 w_1) \\ &= \textbf{u} \cdot (\textbf{v} \times \textbf{w}) \end{align} \]

Form of Linear Equation

A set of equations can be expressed in the form of matrix equation.

\[ \textbf{A}\textbf{X} = \textbf{B} \]

where \(\textbf{A}\) is the coefficient matrix, \(\textbf{X}\) the solution vector and \(\textbf{B}\) the constant vector.

Cramer’s Rule

A system of linear equations has a unique solution if and only if the determinant of the coefficient matrix is nonzero, \(|\textbf{A}| \neq 0\). In this case, the solution is given by \(\textbf{X} = \textbf{A}^{-1}\textbf{B}\), which is called Cramer’s Rule.

Determinant Predicates

Determinants are also useful in concisely expressing geometrical tests.

ORIENT2D(A, B, C)

Let \(A = (a_x, a_y)\), \(B = (b_x, b_y)\) and \(C = (c_x, c_y)\) be three 2D points, and

let ORIENT2D(A, B, C) be defined as

\[ \text{ORIENT2D}(A, B, C) = \begin{vmatrix} a_x & a_y & 1 \\ b_x & b_y & 1 \\ c_x & c_y & 1 \end{vmatrix} = \begin{vmatrix} a_x - c_x & a_y - c_y \\ b_x - c_x & b_y - c_y \end{vmatrix} \]

- if

ORIENT2D(A, B, C)> 0, \(C\) lies to the left of the directed line \(AB\) . Equivalently, the triangle \(ABC\) is oriented counterclockwise. - if

ORIENT2D(A, B, C)< 0, \(C\) lies to the right of the directed line \(AB\). Equivalently, the triangle \(ABC\) is oriented clockwise. - when

ORIENT2D(A, B, C)= 0, the three points are collinear.

The determinant can be seen as the implicit equation of the 2D line through \(A\) and \(B\) by defining \(L(x, y)\) as follows

\[ L(x, y) = \begin{vmatrix} a_x & a_y & 1 \\ b_x & b_y & 1 \\ x & y & 1 \end{vmatrix} \]

ORIENT3D(A, B, C, D)

Given four 3D points \(A = (a_x, a_y,

a_z)\), \(B = (b_x, b_y, b_z)\),

\(C = (c_x, c_y, c_z)\) and \(D = (d_x, d_y, d_z)\), define

ORIENT3D(A, B, C, D) as

\[ \begin{align} &\text{ORIENT3D}(A, B, C, D) \\ &= \begin{vmatrix} a_x & a_y & a_z & 1 \\ b_x & b_y & b_z & 1 \\ c_x & c_y & c_z & 1 \\ d_x & d_y & d_z & 1 \end{vmatrix} = \begin{vmatrix} a_x - d_x & a_y - d_y & a_z - d_z \\ b_x - d_x & b_y - d_y & b_z - d_z \\ c_x - d_x & c_y - d_y & c_z - d_z \end{vmatrix} \\ &= (A - D) \cdot ((B - D) \times (C - D)) \end{align} \]

- if

ORIENT3D(A, B, C, D)< 0, \(D\) lies above the supporting plane of triangle \(ABC\), in the sense that \(ABC\) appears in counterclockwise order when viewed from \(D\). - if

ORIENT3D(A, B, C, D)> 0, \(D\) instead lies below the plane \(ABC\). - when

ORIENT3D(A, B, C, D)= 0, the four points are coplaner.

Alternatively, the determinant can be seen as the implicit equation of the 3D plane \(P(x, y,z ) = 0\) through points \(A, B, C\) as

\[ P(x, y, z) = \begin{vmatrix} a_x & a_y & a_z & 1 \\ b_x & b_y & b_z & 1 \\ c_x & c_y & c_z & 1 \\ x & y & z & 1 \end{vmatrix} \]

INCIRCLE2D(A, B, C, D)

Given four 3D points \(A = (a_x,

a_y)\), \(B = (b_x, b_y)\),

\(C = (c_x, c_y)\) and \(D = (d_x, d_y)\), define

INCIRCLE2D(A, B, C, D) as

\[ \begin{align} & \text{INCIRCLE2D}(A, B, C, D) \\ &= \begin{vmatrix} a_x & a_y & a_x^2 + a_y^2 & 1 \\ b_x & b_y & b_x^2 + b_y^2 & 1 \\ c_x & c_y & c_x^2 + c_y^2 & 1 \\ d_x & d_y & d_x^2 + d_y^2 & 1 \end{vmatrix} \\ &= \begin{vmatrix} a_x - d_x & a_y - d_y & (a_x - d_x)^2 + (a_y - d_y)^2 \\ b_x - d_x & b_y - d_y & (b_x - d_x)^2 + (b_y - d_y)^2 \\ c_x - d_x & c_y - d_y & (c_x - d_x)^2 + (c_y - d_y)^2 \end{vmatrix} \end{align} \]

Let the triangle \(ABC\)

appear in counterclockwise order, as indicated by

ORIENT2D(A, B, C) > 0, then

- if

INCIRCLE2D(A, B, C, D)> 0, \(D\) lies inside the circle through the three points \(A, B\) and \(C\). - if

INCIRCLE(A, B, C, D)< 0, \(D\) lies outside the circle. - when

INCIRCLE(A, B, C, D)= 0, the four points are cocircle.

If ORIENT2D(A, B, C) < 0, then the result is

reversed.

INSPHERE(A, B, C, D, E)

Given five 3D points \(A = (a_x, a_y,

a_z)\), \(B = (b_x, b_y, b_z)\),

\(C = (c_x, c_y, c_z)\), \(D = (d_x, d_y, d_z)\), and \(E = (e_x, e_y, e_z)\), define

INSPHERE(A, B, C, D, E) as

\[ \begin{align} & \text{INSPHERE}(A, B, C, D, E) \\ &= \begin{vmatrix} a_x & a_y & a_z & a_x^2 + a_y^2 + a_z^2 & 1 \\ b_x & b_y & b_z & b_x^2 + b_y^2 + b_z^2 & 1 \\ c_x & c_y & c_z & c_x^2 + c_y^2 + c_z^2 & 1 \\ d_x & d_y & d_z & d_x^2 + d_y^2 + d_z^2 & 1 \\ e_x & e_y & e_z & e_x^2 + e_y^2 + e_z^2 & 1 \\ \end{vmatrix} \\ &= \begin{vmatrix} a_x - e_x & a_y - e_y & a_z - e_z & (a_x - e_x)^2 + (a_y - e_y)^2 + (a_z - e_z)^2 \\ b_x - e_x & b_y - e_y & b_z - e_z & (b_x - e_x)^2 + (b_y - e_y)^2 + (b_z - e_z)^2 \\ c_x - e_x & c_y - e_y & c_z - e_z & (c_x - e_x)^2 + (c_y - e_y)^2 + (c_z - e_z)^2 \\ d_x - e_x & d_y - e_y & d_z - e_z & (d_x - e_x)^2 + (d_y - e_y)^2 + (d_z - e_z)^2 \end{vmatrix} \end{align} \]

Let the four points \(A, B, C\) and

\(D\) be oriented such that

ORIENT3D(A, B, C, D) > 0.

- if

INSPHERE(A, B, C, D, E)> 0, \(E\) lies inside the sphere through \(A, B, C\) and \(D\). - if

INSPHERE(A, B, C, D, E)< 0, \(E\) lies outside the sphere. - when

INSPHERE(A, B, C, D, E)= 0, the five points are cospherical.

Vectors

Given vectors \(\textbf{u}, \textbf{v}\) and \(\textbf{w}\) and scalars \(r, s\). Algebraic identities of vectors are listing below:

$$ \[\begin{align} \textbf{u} + \textbf{v} &= \textbf{v} + \textbf{u} \\ (\textbf{u} + \textbf{v}) + \textbf{w} &= \textbf{u} + (\textbf{v} + \textbf{w}) \\ \textbf{u} - \textbf{v} &= \textbf{u} + (-\textbf{v}) \\ -(-\textbf{v}) &= \textbf{v} \\ \textbf{v} + (-\textbf{v}) &= \textbf{0} \\ r(s\textbf{v}) &= (rs)\textbf{v} \\ (r + s)\textbf{v} &= r\textbf{v} + s\textbf{v} \\ s(\textbf{u} + \textbf{v}) &= s\textbf{u} + s\textbf{v} \\ 1\textbf{v} &= \textbf{v} \\ \end{align}\] $$

Dot Product

The dot product (or scalar product) of two vectors is defined as below

\[ \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v} = \sum_{i = 1}^n u_i v_i \]

The length of a vector is the dot product of itself

\[ \|\textbf{v}\|^2 = \textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{v} \]

The smallest angle \(\theta\) between \(\textbf{u}\) and \(\textbf{v}\) satisfies the equation

\[ \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v} = \|\textbf{u}\| \|\textbf{v}\| \cos \theta \]

and thus \(\theta\) can be obtained as

\[ \theta = \cos^{-1} \frac{\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}}{\|\textbf{u}\| \|\textbf{v}\|} \]

Geometrically, the dot product can be seen as the projection of \(\textbf{v}\) onto \(\textbf{u}\), returning the signed distance \(d\) of \(\textbf{v}\) along \(\textbf{u}\) in units of \(\|\textbf{u}\|\)

\[ d = \frac{\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}}{\| \textbf{u} \|} \]

Algebraic identities involving dot products are listed below

\[ \begin{align} \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v} &= \|\textbf{u}\| \|\textbf{v}\| \cos \theta \\ \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{u} &= \|\textbf{u}\|^2 \\ \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v} &= \textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{u} \\ \textbf{u} \cdot (\textbf{v} \pm \textbf{w}) &= \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v} \pm \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{w} \\ r\textbf{u} \cdot s\textbf{v} &= rs(\textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{u}) \end{align} \]

Cross Product

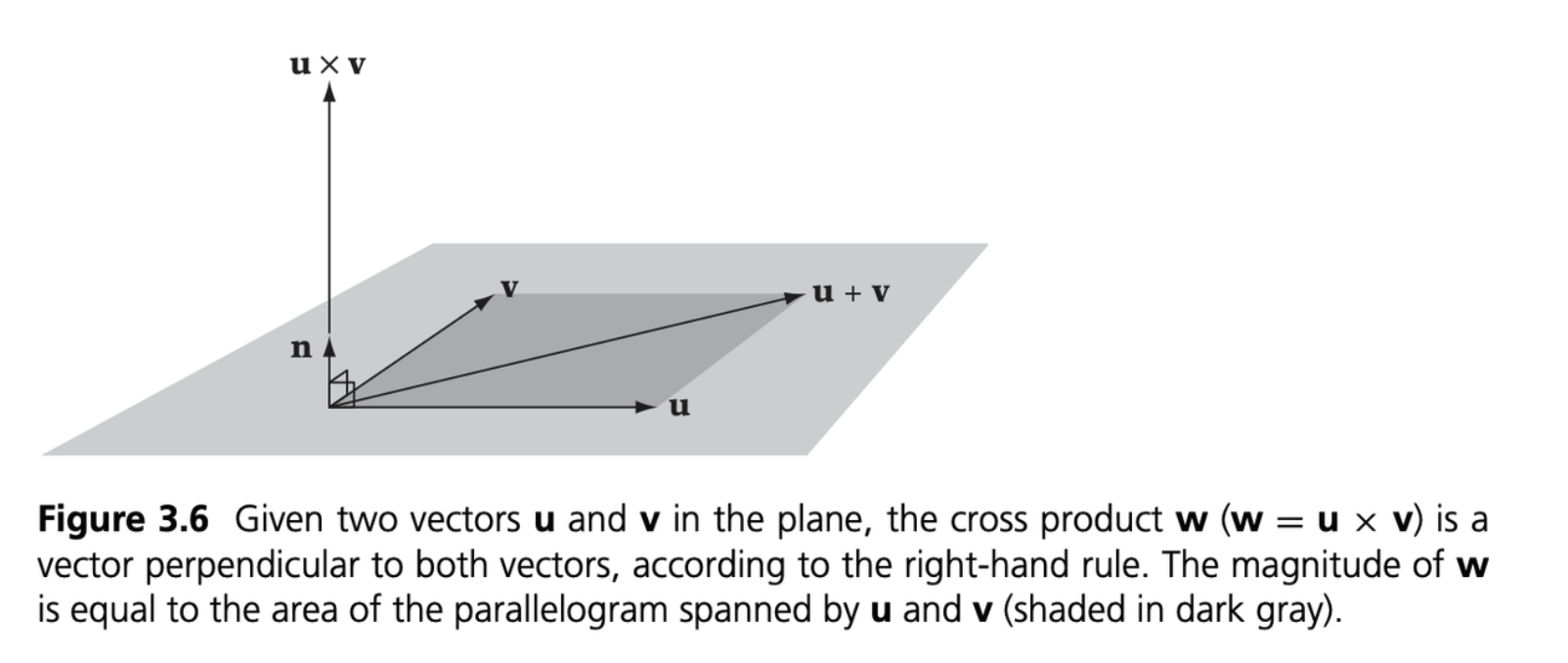

The cross product of two 3D vectors \(\textbf{u} = (u_1, u_2, u_3)\) and \(\textbf{v} = (v_1, v_2, v_3)\) is defined as below

\[ \textbf{u} \times \textbf{v} = (u_2 v_3 - u_3 v_2, -(u_1 v_3 - u_3 v_1), u_1 v_2 - u_2 v_1) \]

The result is a vector perpendicular to \(\textbf{u}\) and \(\textbf{v}\). Its magnitude is equal to the product of the lengths of \(\textbf{u}\) and \(\textbf{v}\) and the sine of the smallest angle \(\theta\) between them. That is,

\[ \textbf{u} \times \textbf{v} = \textbf{n} \|\textbf{u}\| \|\textbf{v}\| \sin \theta \]

where \(\textbf{n}\) is a unit vector perpendicular to the plane of \(\textbf{u}\) and \(\textbf{v}\).

The cross product can aslo be defined as the pseudo-determinant as below

\[ \textbf{u} \times \textbf{v} = \begin{vmatrix} \textbf{i} & \textbf{j} & \textbf{k} \\ u_1 & u_2 & u_3 \\ v_1 & v_2 & v_3 \end{vmatrix} = \begin{vmatrix} u_2 & u_3 \\ v_2 & v_3 \end{vmatrix}\textbf{i} - \begin{vmatrix} u_1 & u_3 \\ v_1 & v_3 \end{vmatrix}\textbf{j} + \begin{vmatrix} u_1 & u_2 \\ v_1 & v_2 \end{vmatrix}\textbf{k} \]

where \(\textbf{i} = (1, 0, 0), \textbf{j} = (0, 1, 0)\) and \(\textbf{k} = (0, 0, 1)\) are unit vectors parallel to the coordinate axes.

Algebraic identities involving cross products are listed below. Let \(\textbf{u}, \textbf{v}, \textbf{w}\) and \(\textbf{r}\) are vectors and \(r, s\) be scalars.

$$ \[\begin{align} \textbf{u} \times \textbf{v} &= -(\textbf{v} \times \textbf{u}) \\ \textbf{u} \times \textbf{u} &= \textbf{0} \\ \textbf{u} \times \textbf{0} &= \textbf{0} \times \textbf{u} \\ \textbf{u} \cdot (\textbf{v} \times \textbf{w}) &= (\textbf{u} \times \textbf{v}) \cdot \textbf{w} \\ (\textbf{u} \pm \textbf{v}) \times \textbf{w} &= \textbf{u} \times \textbf{w} \pm \textbf{v} \times \textbf{w} \\ \| \textbf{u} \times \textbf{v} \| &= \| \textbf{u} \| \| \textbf{v} \| \sin \theta \\ r\textbf{u} \times s\textbf{v} &= rs(\textbf{u} \times \textbf{v}) \\ (\textbf{u} \times \textbf{v}) \cdot (\textbf{w} \times \textbf{x}) &= (\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{w})(\textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{x}) - (\textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{w})(\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{x}) \\ \textbf{u} \times (\textbf{v} \times \textbf{w}) + \textbf{v} \times (\textbf{w} \times &\textbf{u}) + \textbf{w} \times (\textbf{u} \times \textbf{v}) = 0 \end{align}\] $$

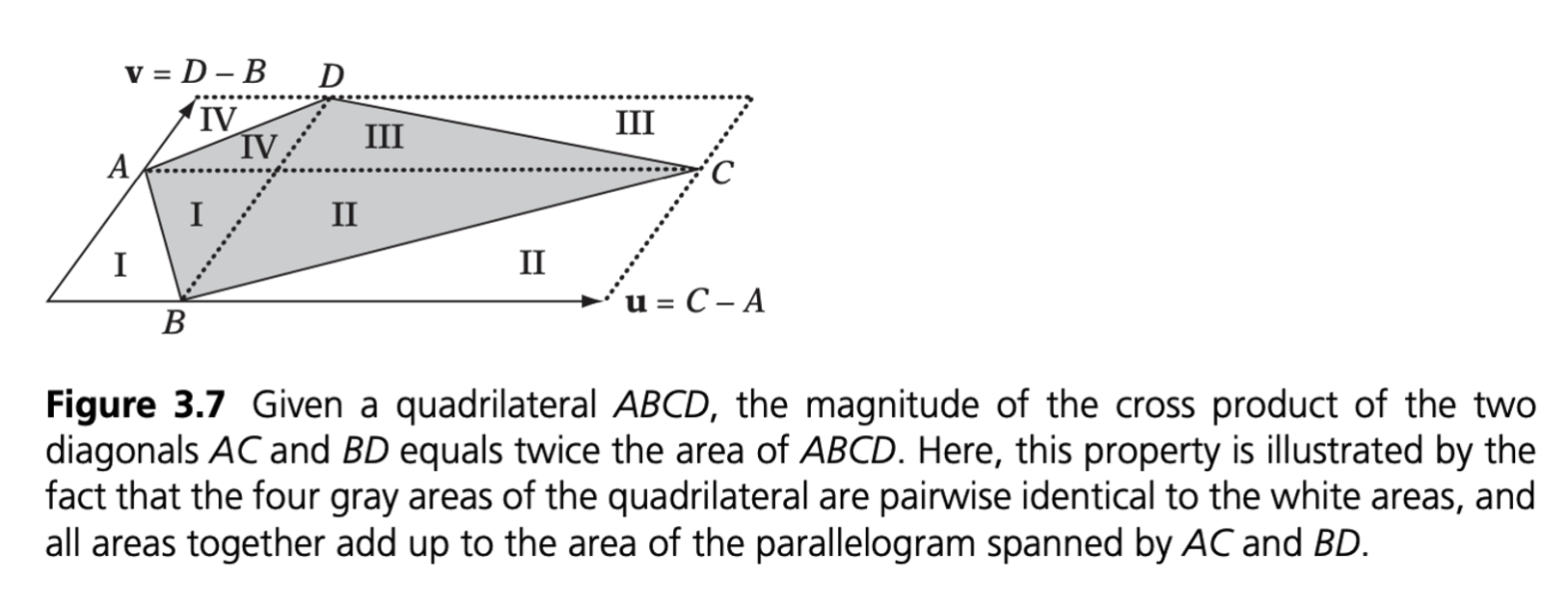

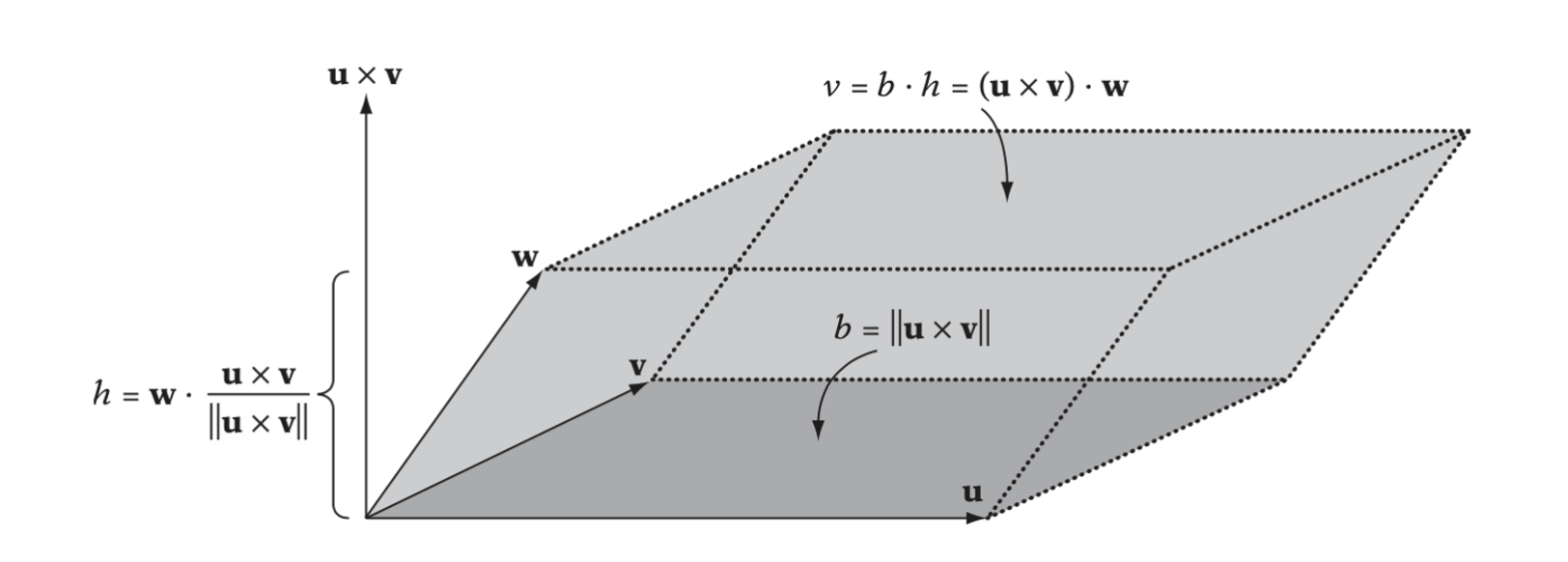

Scalar Triple Product

The scalar triple product is defined as \((\textbf{u} \times \textbf{v}) \cdot \textbf{w}\). Geometrically, the value of the scalar triple product corresponds to the signed volume of a parrallelepiped formed by the three independent vectors \(\textbf{u}, \textbf{v}\) and \(\textbf{w}\).

The scalar triple product also remains constant under the cyclic permutation of its three arguments:

\[ (\textbf{u} \times \textbf{v}) \cdot \textbf{w} = (\textbf{v} \times \textbf{w}) \cdot \textbf{u} = (\textbf{w} \times \textbf{u}) \cdot \textbf{v} \]

Because of these identities, the special notation \([\textbf{u}, \textbf{v} ,\textbf{w}]\) is often used to denote a triple product. The scalar triple product can also be expressed in the form of determinant.

\[ \begin{align} [\textbf{u}, \textbf{v}, \textbf{w}] &= \begin{vmatrix} u_1 & u_2 & u_3 \\ v_1 & v_2 & v_3 \\ w_1 & w_2 & w_3 \end{vmatrix} \\ &= u_1 \begin{vmatrix} v_2 & v_3 \\ w_2 & w_3 \end{vmatrix} - u_2 \begin{vmatrix} v_1 & v_3 \\ w_1 & w_3 \end{vmatrix} + u_3 \begin{vmatrix} v_1 & v_2 \\ w_1 & w_2 \end{vmatrix} \\ &= \textbf{u} \cdot (\textbf{v} \times \textbf{w}) \end{align} \]

Barycentric Coordinates

Barycentric coordinates parameterize the space that can be formed as a weighted combination of a set of reference points.

Consider two points \(A\) and \(B\). A point \(P\) on the line between \(A\) and \(B\) can be expressed as \(P = A + t(B - A) = (1 - t)A + tB\), or simply just \(P = uA + vB\), where \(u + v = 1\). In such a way, \((u, v)\) are the barycentric coordinates of \(P\) with respect to \(A\) and \(B\).

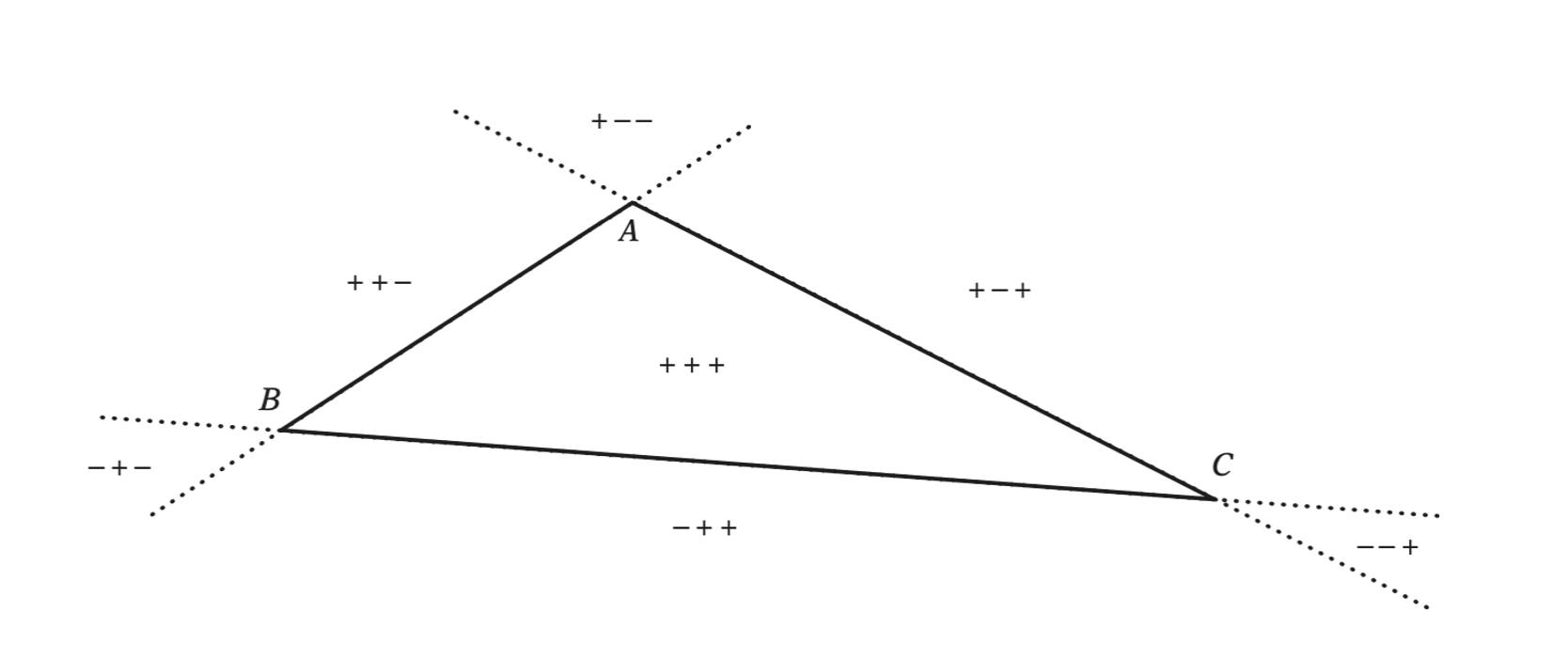

Consider three noncollinear points \(A, B\) and \(C\). Any point in the plane can be expressed as \(P = uA + vB + wC\) for some constants \(u, v\) and \(w\) where \(u + v + w = 1\). The triplet \((u, v, w)\) corresponds to the barycentric coordinates of the point. After reformulation \(P\) can be expressed as

\[ \begin{align} P &= A + v(B - A) + w(C - A) \\ &= (1 - v - w)A + vB + wC \end{align} \]

The barycentric coordinates of a given point \(P\) can be computed as the ratios of the triangle areas of \(PBC, PCA\) and \(PAB\) with respect to the area of the entire triangle \(ABC\). For this reason barycentric coordinates are also called areal coordinates.

u = SignedArea(PBC) / SignedArea(ABC); |

Barycentric coordinates divide the plane of the triangle \(ABC\) into seven regions based on the sign of the coordinate components.

Determining whether a point \(P\) is in a triangle or not can be easily obtained by determining whether all of its barycentric coordinates are positive or not.

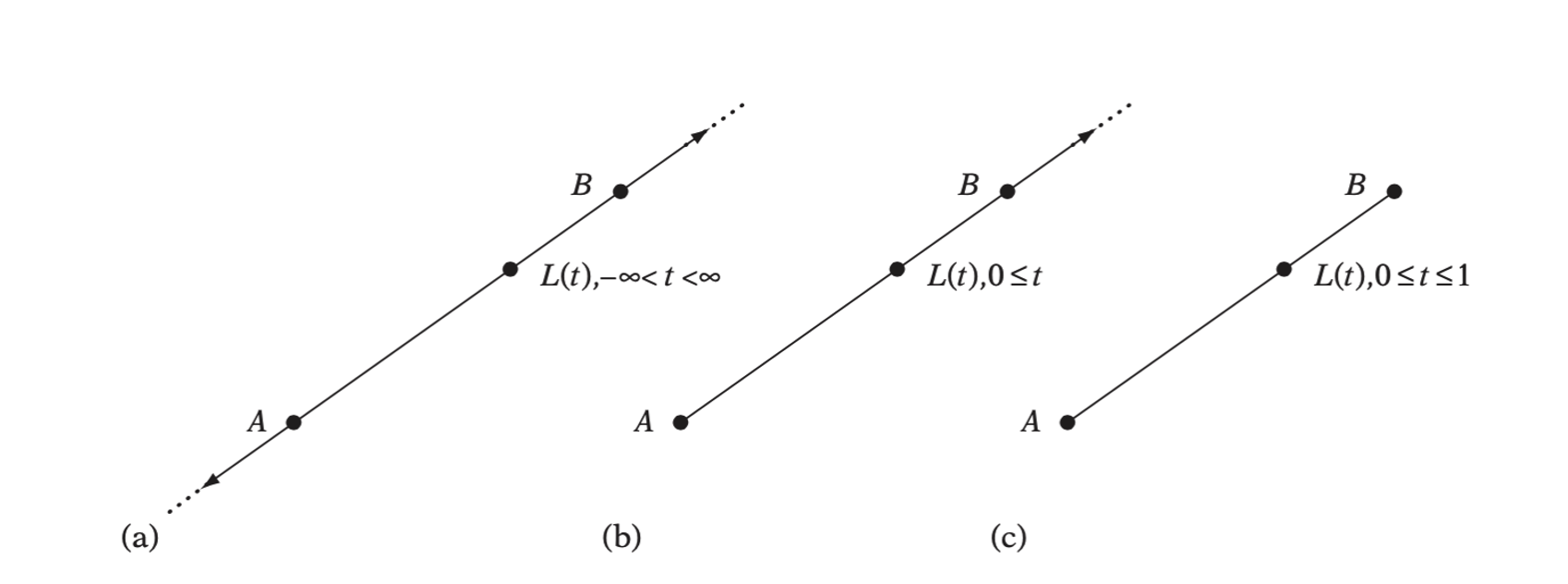

Line, Rays, and Segments

A line is defined as

\[ L(t) = (1 - t)A + tB \]

- A line. (b) A ray. (c) A line segment.

Planes and Halfspaces

There are many ways to express a plane. Given three points \(A, B\) and \(C\), with parametric representation a plane can be given by

\[ P(u, v) = A + u(B - A) + v(C - A) \]

Let \(\textbf{n}\) be the normal vector of the plane and \(P\) be the fixed point on the plane and \(X\) be any point on the plane. Then the point-normal form of the plane is

\[ \textbf{n} \cdot (X - P) = 0 \]

It can also be expressed as

\[ \textbf{n} \cdot X = d \]

where \(d = \textbf{n} \cdot P\) is the constant-normal form of the plane. When \(\textbf{n}\) is unit, \(|d|\) equals the distance of the plane from the origin.

Planes in arbitrary dimensions are referred to as hyperplanes: planes with on less dimension than the space they are in. Any hyperplanes divides the space into two infinite sets of points on either side of the plane. The positive halfspace lies on the side in which the plane normal points, while the other side is called negative halfspace.

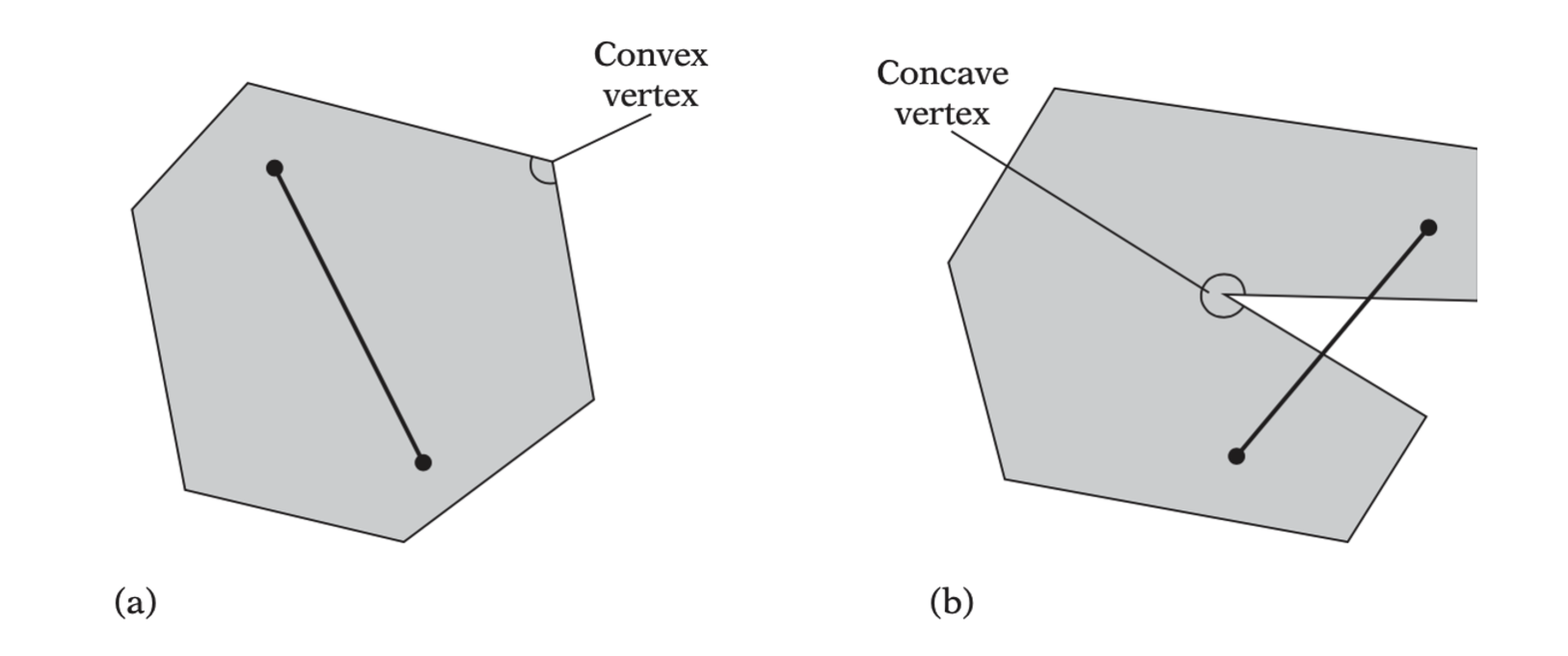

Polygons

A polygon is a closed figure with \(n\) sides, defined by an ordered set of three or more points in the plane in such a way that each point is connected to the next with a line segment. The line segments that make up the polygon boundary are referred to as the polygon sides or edges. And the points themselves are called the polygon vertices.

A polygon \(P\) is a convex polygon if all the line segments between any two points of \(P\) lie fully inside \(P\). A polygon that is not convex is called a concave polygon.

- For a convex polygon, the line segment connecting any two points of the polygon must lie entirely inside the polygon. (b) If two points can be found such that the segment is partially outside the polygon, the polygon is concave.

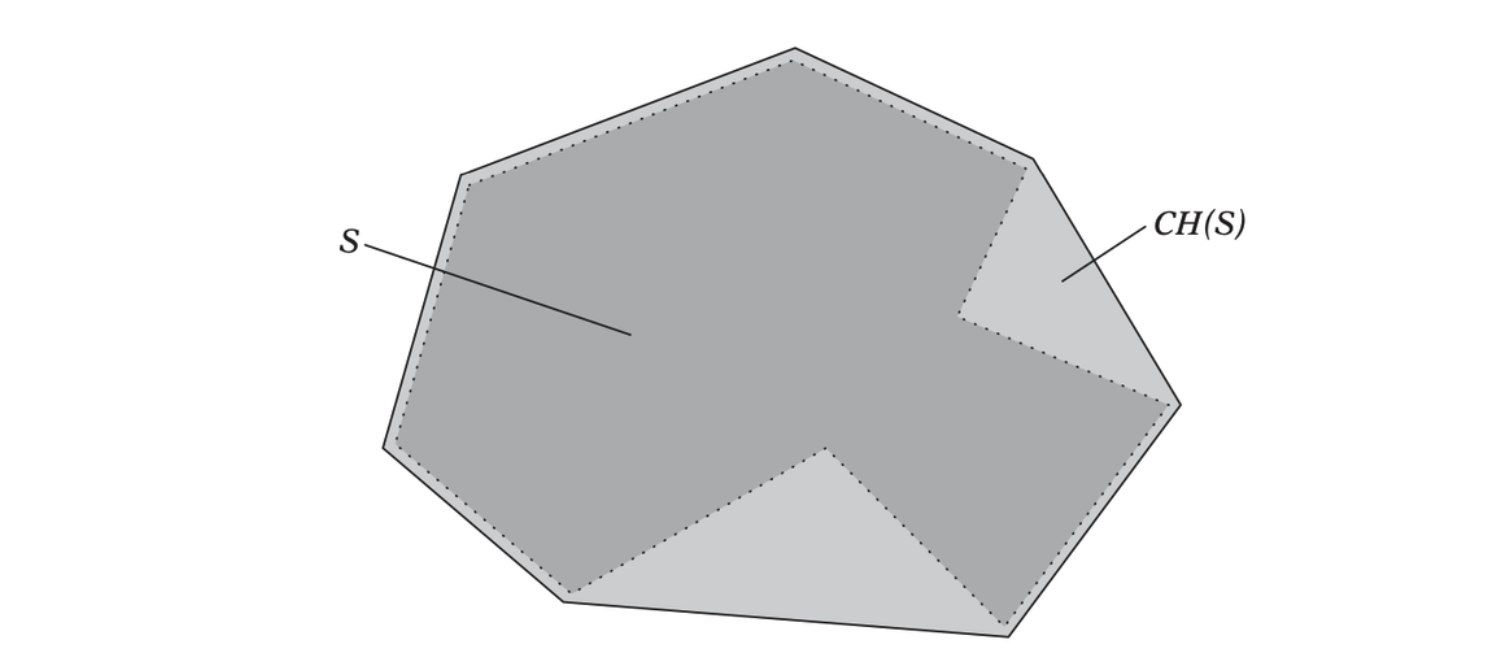

Convex Hull

A convex point set \(S\) is a set of points wherein the line segment between any two points in \(S\) is also in \(S\). Given a point set \(S\), the convex hull of \(S\), denoted \(CH(S)\), is the smallest convex point set fully containing \(S\).

Related to the convex hull is the affine hull, \(AH(S)\). The affine hull is the lowest dimensional hyperplane that contains all points of \(S\).

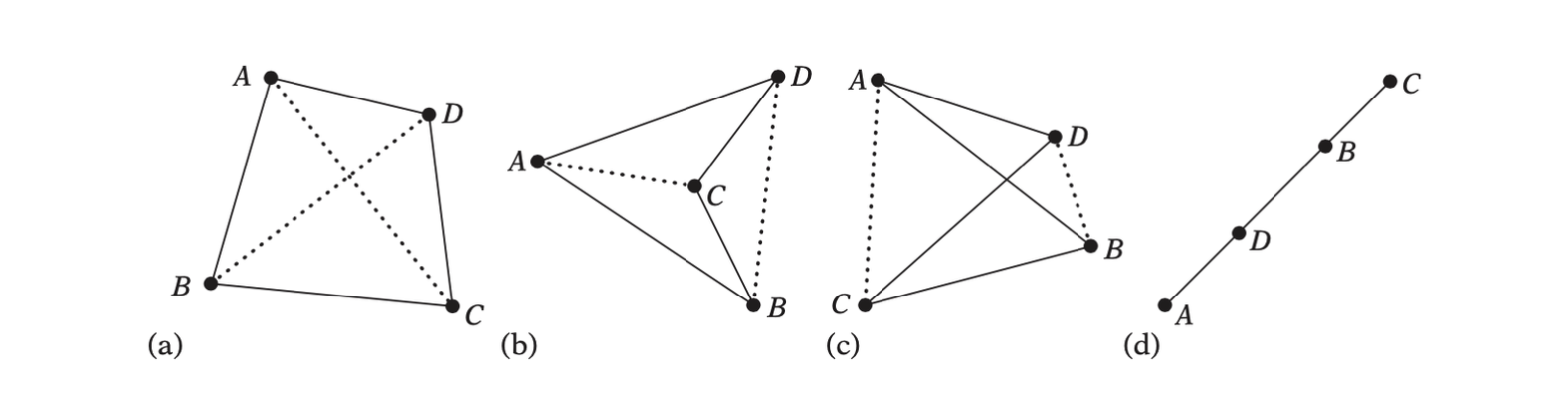

Testing Polygonal Convexity

Assuming all vertices of the quad \(ABCD\) lie in the same plane, the quad is convex if and only if its two diagonals lie fully in the interior of the quad. This test is equivalent to testing if the two line segments \(AC\) and \(BD\) intersect each other.

- Intersection of the segments is equivalent to the points \(A\) and \(C\) lying on the opposite sides of the line through \(BD\).

- And the above test is equivalent to the triangle \(BDA\) having opposite winding to \(BDC\).

- And the opposite winding can be detected by computing the normals of the triangles and examining the sign of the dot product between the normals of the triangles to be compared.

Hence the quad is threfore convex if

\[ (BD \times BA) \cdot (BD \times BC) < 0 \text{ and } \\ (AC \times AD) \cdot (AC \times AB) \]

Polyhedra

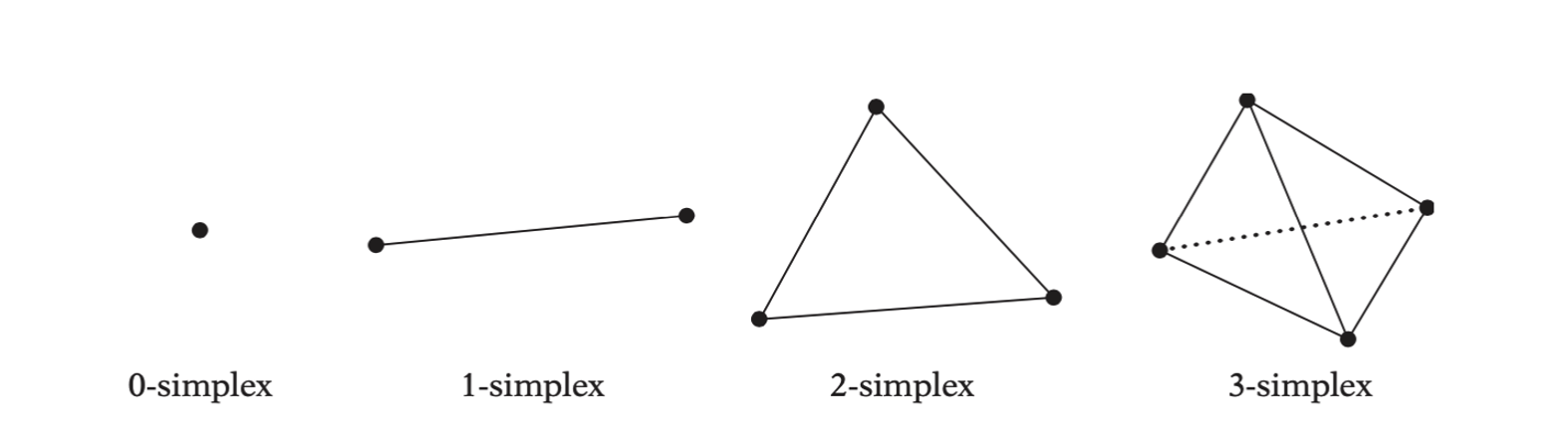

A polyhedron is the 3D counterpart of a polygon. A d-simplex is the convex hull of d+1 affinely independent points in d-dimensional space. A simplex is a d-simplex for some given d.

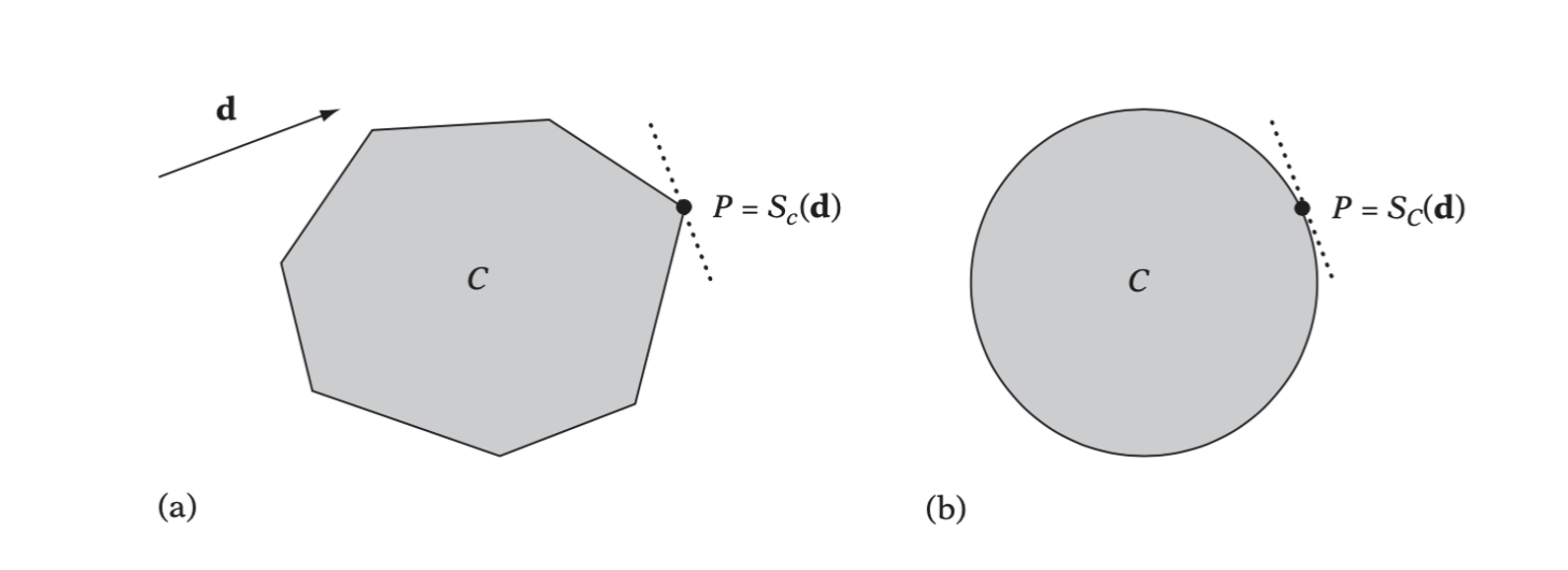

For a general convex set \(C\), a point from the set most distant along a given direction is called a supporting point of \(C\). More specifically, \(P\) is a supporting point of \(C\) if for a given direction \(\textbf{d}\) it holds that \(\textbf{d} \cdot P = \max \{ \textbf{d} \cdot V: V \in C \}\). Supporting points are sometimes called extreme points. They are not necessarily unique.

A support mapping (or support function) is a function, \(S_C(\textbf{d})\), associated with a convex set \(C\) that maps the direction \(\textbf{d}\) into a supporting point of \(C\).

A supporting plane is a plane through a supporting point with the given direction as the plane normal.

A separating plane of two convex sets is a plane such that one set is fully in the positive halfspace and the other fully in the negative halfspace. An axis orthogonal to a separating plane is referred to as a separating axis.

Computing Convex Hulls

Among other uses, convex hull can serve as tight bounding volumes for collision geometry.

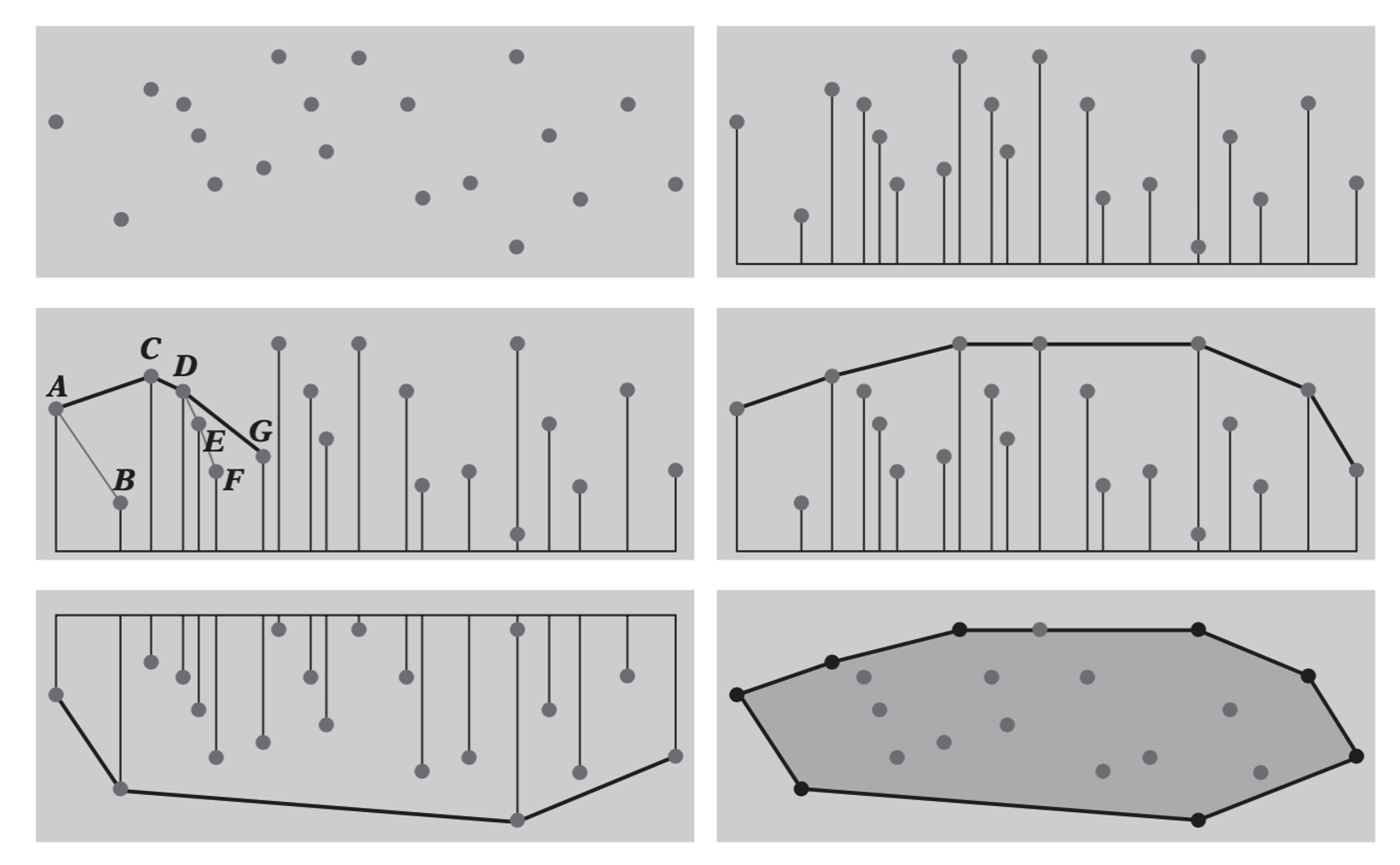

Andrew’s Algorithm

This is a 2D convex hull algorithm.

- The first pass, sort the points in the given point set from left to right.

- The second pass construct the upper chain of the convex hull.

- The third pass construct the lower chain of the convex hull.

Combining two chains to form the convex hull. The upper chain is constructed in the following manner.

- Add the left most two points into the chain.

- For each of the following points, test whether the point is on the

right side of the chain.

- if the point is on the right side of the chain, add it to the chain.

- if the point lies on the left of the chain, then remove the last point of the chian and test until the current point lies on the right of the chain.

The lower chain can be constructed with a similar manner.

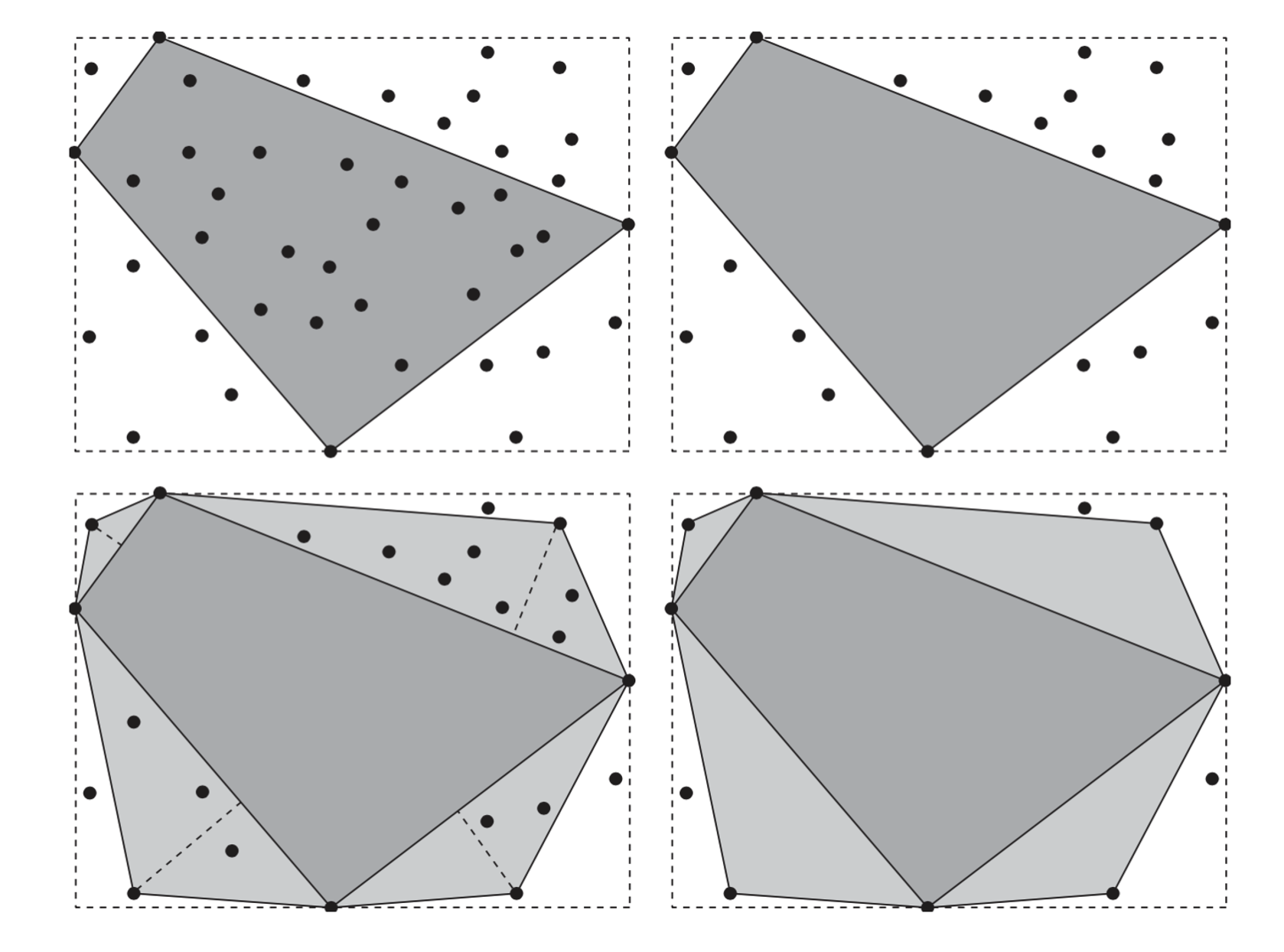

The Quickhull Algorithm

This method works in both 2D and 3D.

- Start by finding four extreme points of the given point set, forming

the initial convex hull.

- Abandoning all points inside the convex hull.

- Searching for farthest point of each of the sides of the current

convex hull.

- Add them to the current convex hull.

- Abandoning all points inside current the convex hull.

- Repeat 2 until no new points are discovered.

Voronoi Regions

Given a polyhedron \(P\), let a feature of \(P\) be on of its vertices, edges, or faces. The Voronoi region of a feature \(F\) of \(P\) is then the set of points in space closer to \(F\) than to any other feature of \(P\). The boundary planes of a Voronoi region are referred to as Voronoi planes.

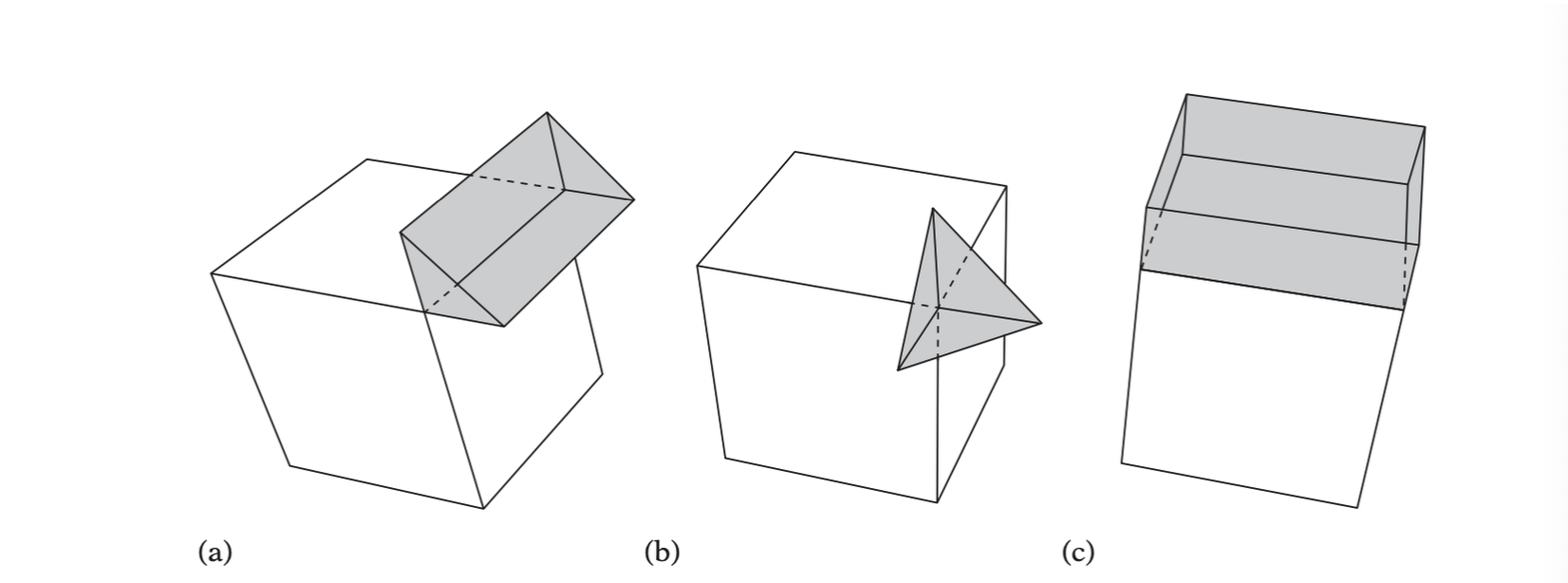

The three types of Voronoi feature regions of a 3D cube. (a) An edge region. (b) A vertex region. (c) A face region.

Minkowski Sum and Difference

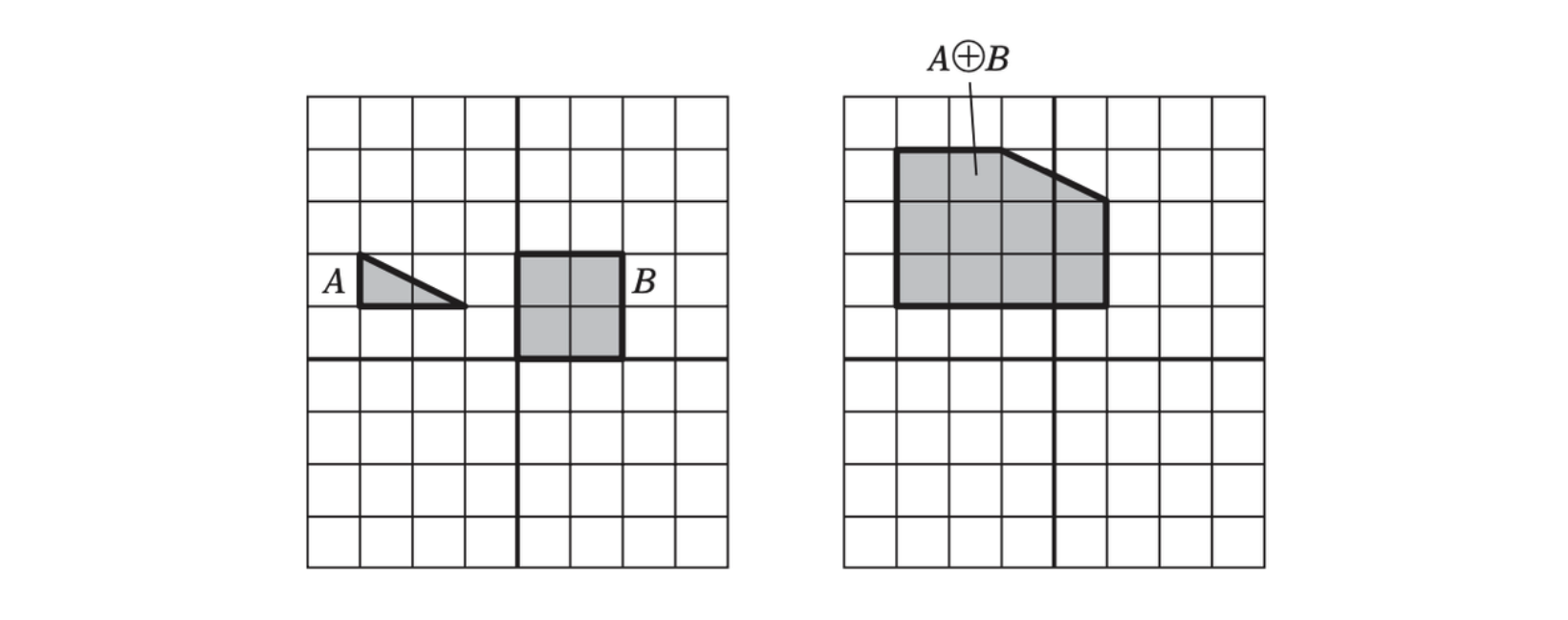

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two point sets, and let \(\textbf{a}\) and \(\textbf{b}\) be the position vectors corresponding to pairs of points in \(A\) and \(B\). The Minkowski sum, \(A \oplus B\), is defined as the set

\[ A \oplus B = \{ \textbf{a} + \textbf{b}: \textbf{a} \in A, \textbf{b} \in B\} \]

Visully, the Minkowski sum can be seen as the region swept by \(A\) translated to every point in \(B\)(or vise versa).

And analogously the Minkowski difference is defined as below

\[ A \ominus B = \{ \textbf{a} - \textbf{b}: \textbf{a} \in A, \textbf{b} \in B\} \]

The Minkowski difference is obtained by adding \(A\) to the reflection of \(B\) about the origin; that is \(A \ominus B = A \oplus (-B)\).

Let \(A, B\) be two point sets, the minimum distance between \(A\) and \(B\) is defined as below

\[ \begin{align} \text{distance}(A, B) &= \min \{ \| \textbf{a} - \textbf{b} \|: \textbf{a} \in A, \textbf{b} \in B \} \\ &= \min \{ \| \textbf{c} \| : \textbf{c} \in A \ominus B\} \end{align} \]