Spatial Partitioning

Spatial partitioning techniques provide broad-phase processing by dividing space into regions and testing if objects overlap the same region of space.

Uniform Grids

A very effective space subdivision scheme is to overlay space with a regular grid. The grid divides space into a number of regions, or grid cells, or equal size. Each object is then associated with the cells it overlaps.

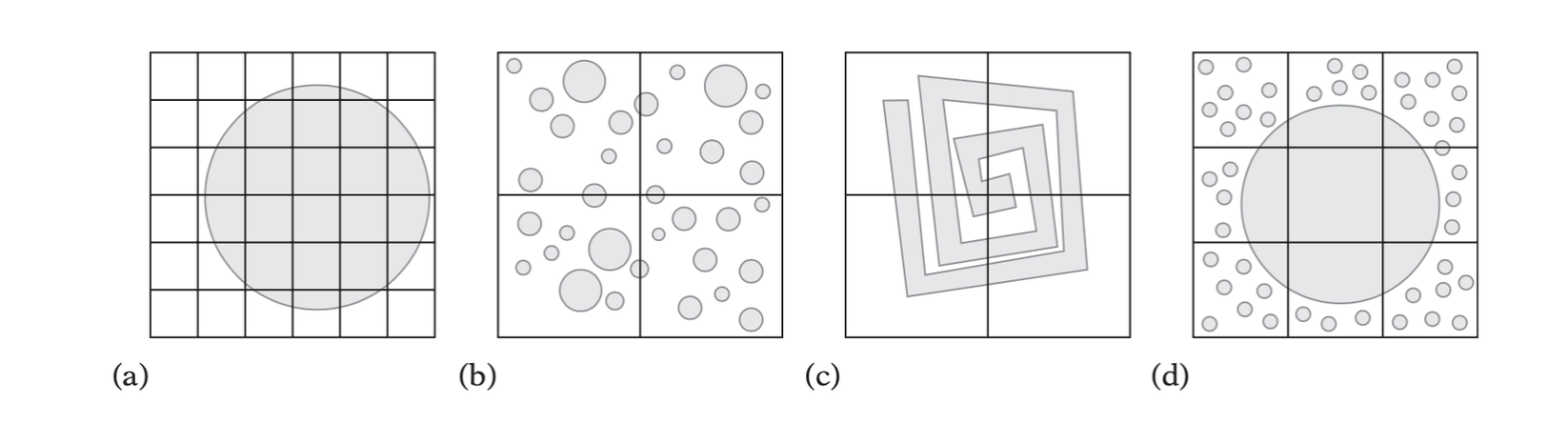

Cell Size Issues

- The grid is too fine. If the cells are too small, a large number of cells must be updated with associativity information for the object, which will take both extra time and space.

- The grid is too coarse (with respect to object size). If the objects are small and the grid cells are large, there will be many objects in each cell.

- The grid is too coarse (with respect to object complexity). In this case, the grid cell matches the objects well in size. However, the object is much too complex, affecting the pairwise object comparison.

- The grid is both too fine and too coarse. If the objects are of greatly varying sizes, the cells can be too large for the smaller objects while too small for th largest objects.

In ray tracing a popular method for determining the grid dimension has been the \(n^{1/3}\) rule: given \(n\) objects, divide space into a \(k \times k \times k\) grid, with \(k = n^{1/3}\). The ratio of cells to objects is referred to as the grid density.

Grids as Arrays of Linked Lists

The natural way of storing objects in a grid is to allocate an array of corresponding dimension, mapping grid cells to array elements one-to-one. To handle the case of multiple objects ending up in a given cell, each array element would point to a linked list of objects, or be NULL if empty.

Hashed Storage and Infinite Grids

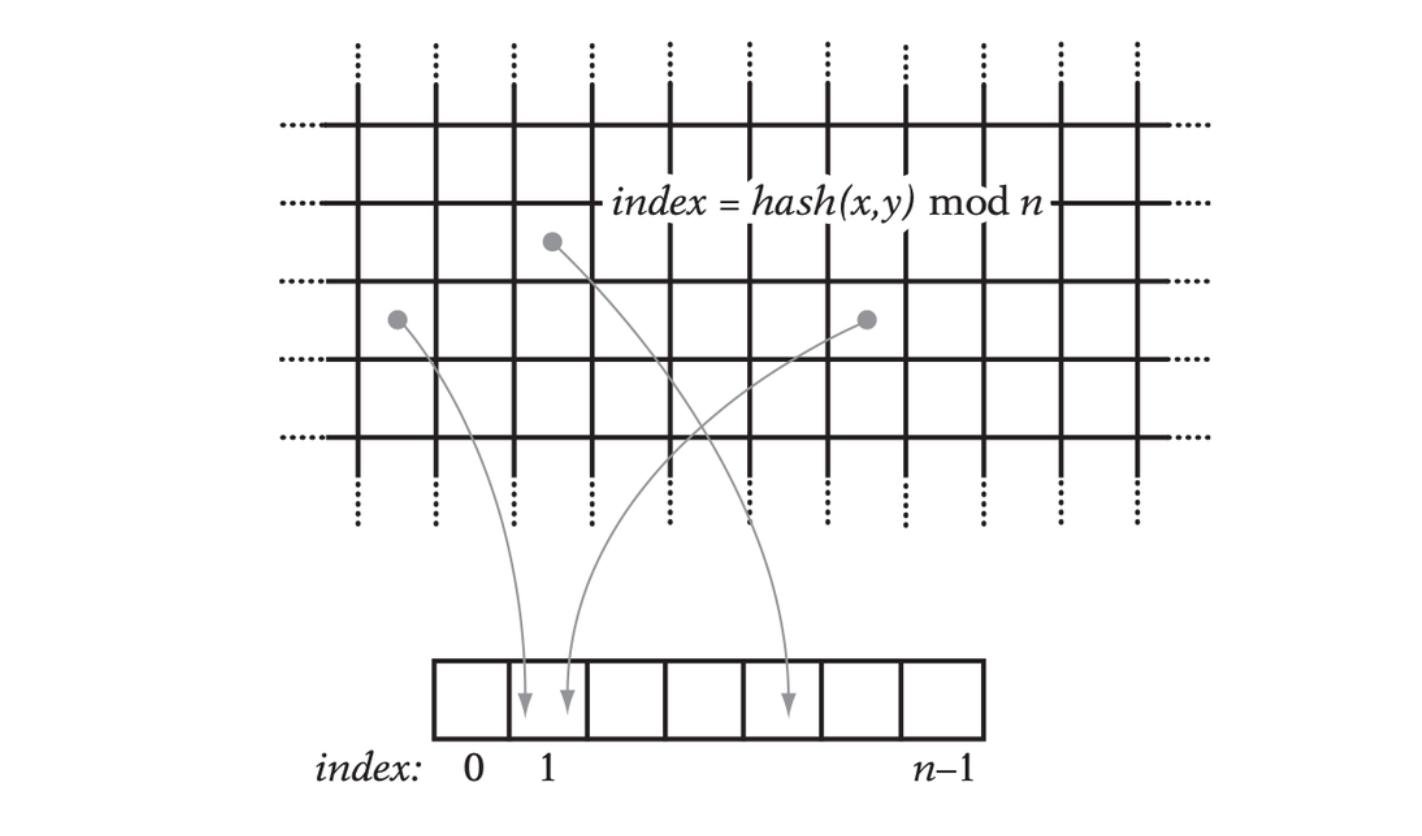

The most effective alternative to using a dense array to store the grid is to map each cell into a hash table of a fixed set of \(n\) buckets. In this scheme, the buckets contain the linked lists of objects.

A (potentially infinite) 2D grid is mapped via a hash function into a small number of hash buckets.

// Cell position |

Although the world may consist of an infinite amount of cells, only a finite number of them are overlapped by objects at a given time. Thus, the storage required for a hashed grid is related to the number of objects and is independent of the grid size.

Storing Static Data

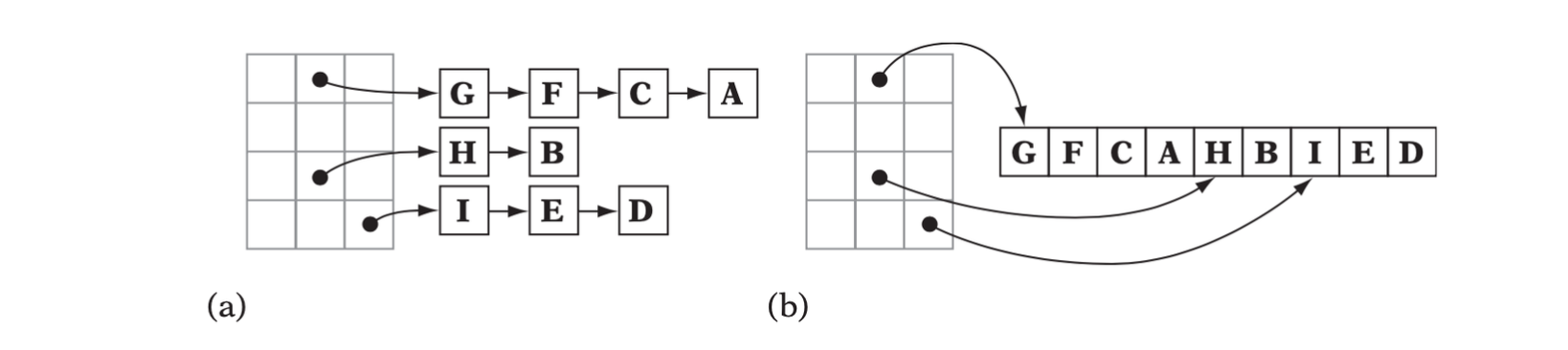

When the grid is static, the need for a linked list can be removed and all cell data can be stored in a single contiguous array.

- A grid storing static data as lists.(b)The same grid with the static data stored into an array.

Implicit Grids

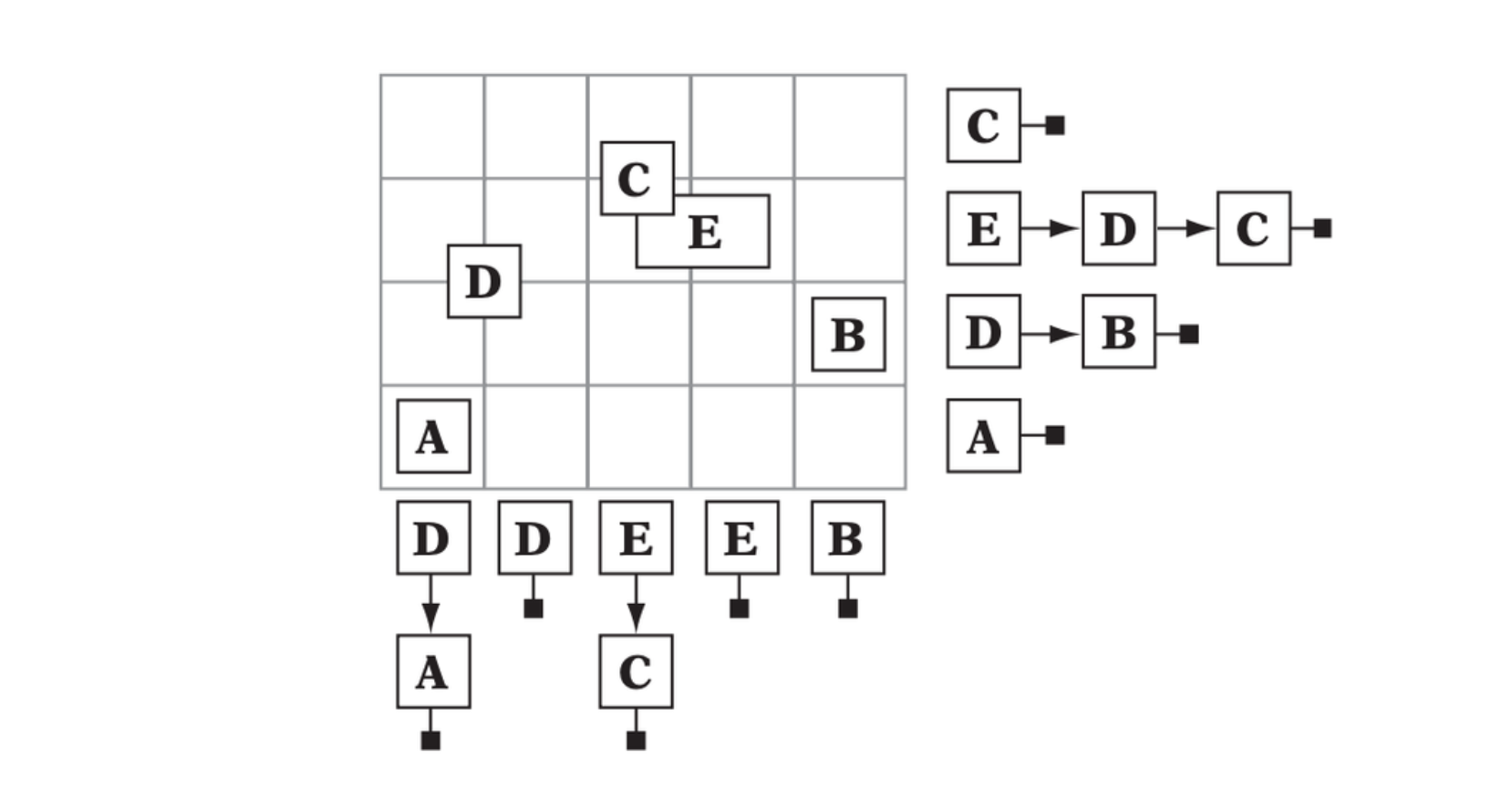

As the Cartesian product of two or more arrays, the grid is now presented by two arrays (three in 3D), wherein one array corresponds to the grid rows and the other to the grid columns. An object is inserted into the grid by adding it to the lists of the grid cells it overlaps, for both the row and column array.

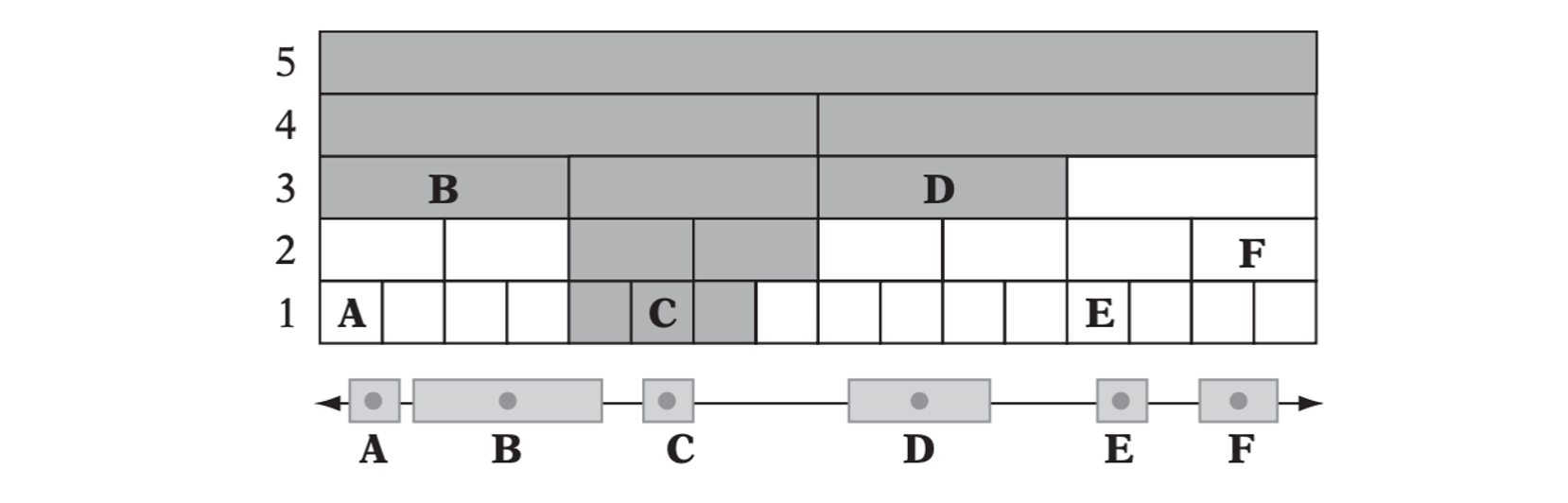

A 4 × 5 grid implicitly defined as the intersection of 9 (4 + 5) linked lists. Five objects have been inserted into the lists and their implied positions in the grid are indicated.

Uniform Grid Object-Object Test

Grid cell sizes are usually constrained to be larger than the largest object. This way, an object is guaranteed to overlap at most the immediately neighboring cells.

One Test at a Time

Consider the case in which objects are associated with a single cell only. When a given object is associated with its cell, in addition to testing agiasnt the objects associated with that cell additional neighboring cells must also be tested. Which cells have to be tested depends on how objects can overlap into other cells and what feature has been used to associate an object with its cell. The choice of feature generally stands between:

- the object bounding sphere center.

- the minimum (top leftmost) corner of the AABB.

If objects have been placed with respect to their centers, any object in the neighboring cells could overlap a cell boundary of this cell and be in collision with the current object.

// Objects placed in single cell based on their bounding sphere center. |

If instead the minimum corner of the AABB has been used, most neighboring cells have to be tested only if the current object actually overlaps into them.

// Objects placed in single cell based on AABB minimum corner vertex. |

If objects have been placed in all cells they overlap the single object test would have to check only those exact cells the AABB overlaps, as all colliding objects are guaranteed to be in those cells.

// Objects placed in all cells overlapped by their AABB. |

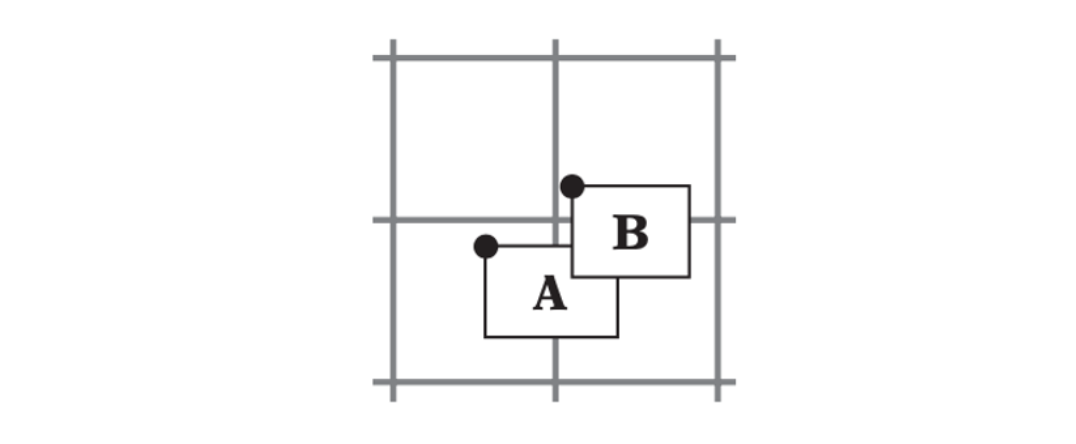

Objects A and B are assigned to a cell based on the location of their topleft-hand corners. In this case, overlap may occur in a third cell. Thus, to detect intersection between objects cells must be tested against their NE or SW neighbor cells.

All Tests at a Time

If instead of testing a single object at a time all objects are tested at the same time, the single-cell placement case can be optimized utilizing the fact that object pair checking is commutative.

If objects have been placed with respect to their centers

// Objects placed in single cell based on their bounding sphere center. |

The case in which objects are placed in a single cell based on the minimum corner point can be similarly simplified.

// Objects placed in single cell based on AABB minimum corner vertex. |

Hierarchical Grids

The most significant problem with uniform grids is their inability to deal with objects of greatly varying sizes in a graceful way. The size problem can effectively be addressed by the use of hierarchical grids (or hgrids), a grid structure particularly well suited to holding dynamically moving objects.

Given a hierarchy containing \(n\) levels of grids and letting \(r_k\) represent the size of the grid cels at level \(k\) in the hierarchy, the grids are arranged in increasing cell size order, with \(r_1 < r_2 < \cdots < r_n\).

To minimize the number of neighboring cells that have to be tested for collisions objects are inserted into the hgrid at the level where the cells are large enough to contain the bounding volume of the object. Given an object \(P\), this level \(L\) is denoted \(L = \text{Level}(P)\). This way, the object is guaranteed to overlap at most four cells (or eight, for a 3D grid).

A small 1D hierarchical grid. Six objects, A through F, have each been inserted in the cell containing the object center point, on the appropriate grid level. The shaded cells are those that must be tested when performing a collision check for object C.

Let the cells at level 1 just encompass the smallest objects. Then successively double the cell size so that cells of level \(k + 1\) are twice as wide as cells of level \(k\). Repeat the doubling process until the highest-level cells are large enough to encompass the largest objects.

Basic Hgrid Implementation

The minimal structure of hgrid is as below:

struct HGrid { |

It is assumed that objects are inserted into the hgrid based on their bounding spheres. Let the object representation contain the following variables.

struct Object { |

Adding an Object

Adding an object into the hgrid can be done as follows.

void AddObjectToHGrid(HGrid *grid, Object *obj) { |

Removing an Object

Removing an object from the hgrid can be done in a corresponding manner.

void RemoveObjectFromHGrid(HGrid *grid, Object *obj) { |

Checking an Object for Collision

Checking an object for collision against objects in the hgrid can be done as follows. It is assume that nothing is known about the number of objects tested at a time, and thus all grid levels are traversed.

// Test collisions between object and all objects in hgrid |

Trees

Trees form good representations for spatial partitioning.

Octrees (and Quadtrees)

The archetypal tree-based spatial partitioning method is the octree. It is an axis-aligned hierarchical partitioning of a volume of 3D world space.

- Each parent node has eight children.

- Each node has a finite volume associated with it.

- The root node volume is taken to be the smallest AABB fully enclosing the world. The volume is then subdivided into eight smaller equal-size subcubes.

The octree node data structure is as below.

// Octree node data structure |

Octree Object Assignment

Octrees may be built to contain either static or dynamic data.

- The data may be the primitives forming the world environment.

- The data may by the moving entities in the world.

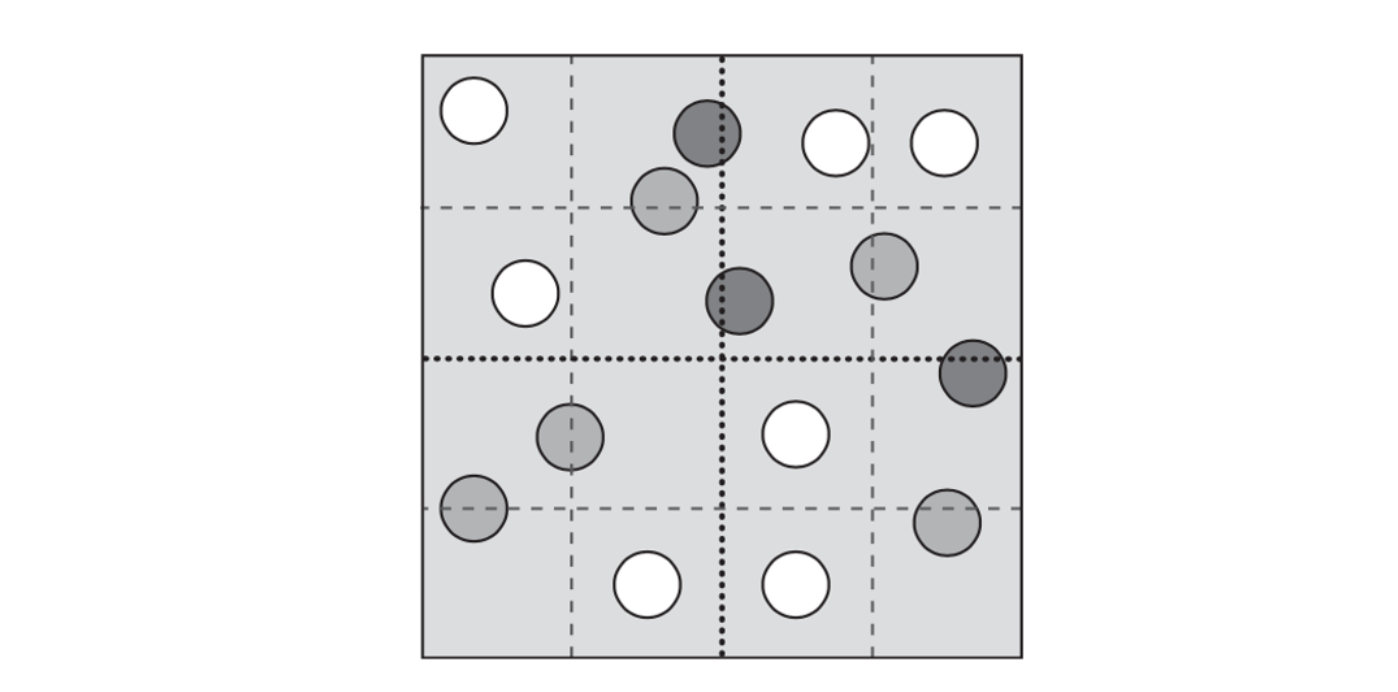

A quad tree node with the first level of subdivision shown in black dotted lines, and the following level of subdivision in gray dashed lines. Dark gray objects overlap the first- level dividing planes and become stuck at the current level. Medium gray objects propagate one level down before becoming stuck. Here, only the white objects descend two levels.

The process of building an octree is as below.

// Preallocates an octree down to a specific depth |

The structure of the object is as follows.

struct Object { |

Octree Object Insertion

The code for inserting an object is as follows.

void InsertObject(Node *pTree, Object *pObject) { |

Octree Object Collision Test

// Tests all objects that could possibly overlap due to cell ancestry and coexistence |

Loose Octrees

An effective way of dealing with straddling objects is to expand the node volumes by some amount to make them partially overlapping. The resulting relaxed octrees have been dubbed loose octrees.

k-d Trees

A generalization of octrees and quadtrees can be found in the k-dimensional tree, or k-d tree. Here, \(k\) represents the number of dimensions subdivided, which does not have to match the dimensionality of the space used.

Instead of simultaneously dividing space in two or three dimensions, the k-d tree divides space along one dimension at a time. One level of an octree can be seen as a three-level k-d tree split along x, then y, then z.

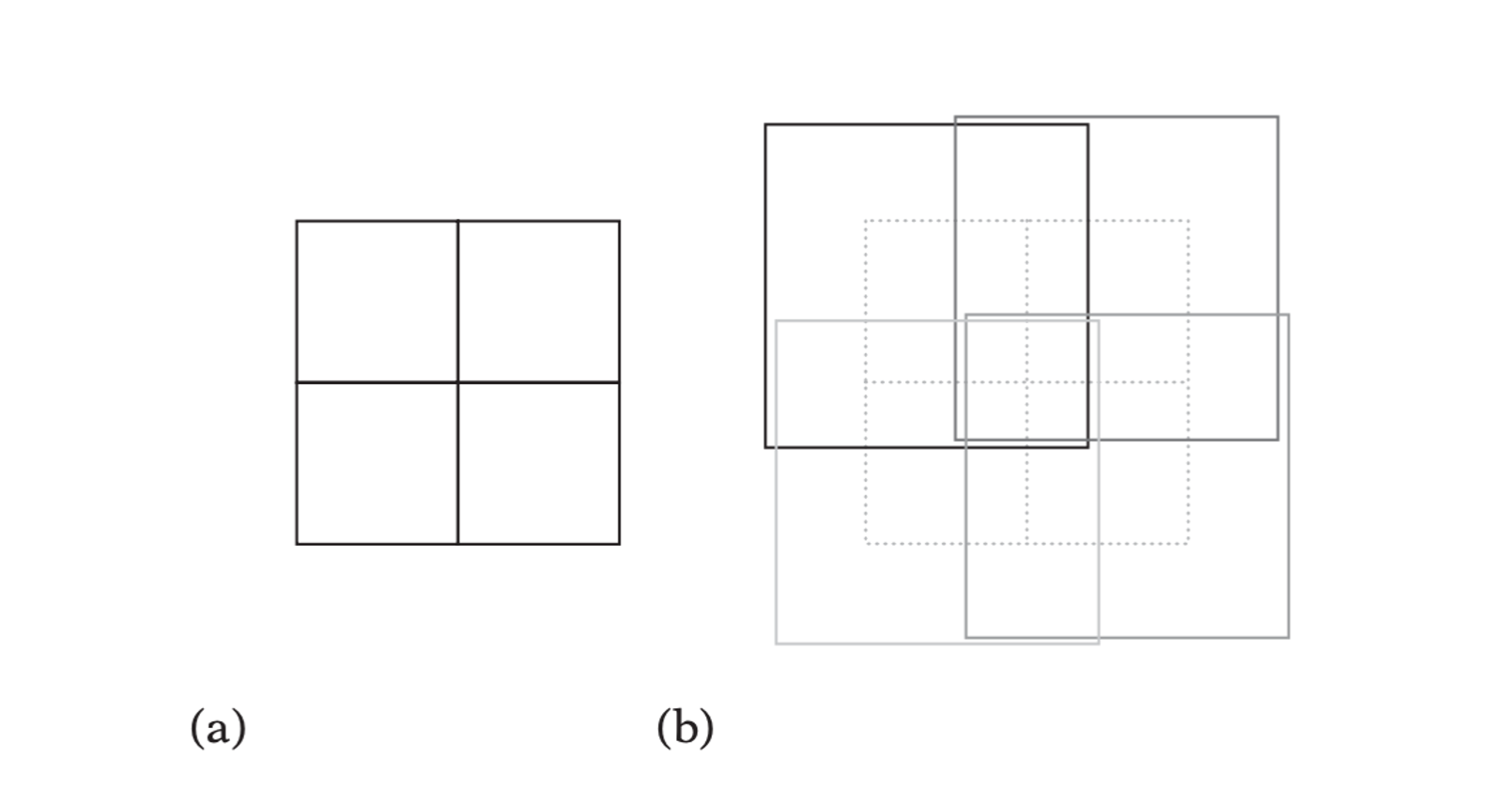

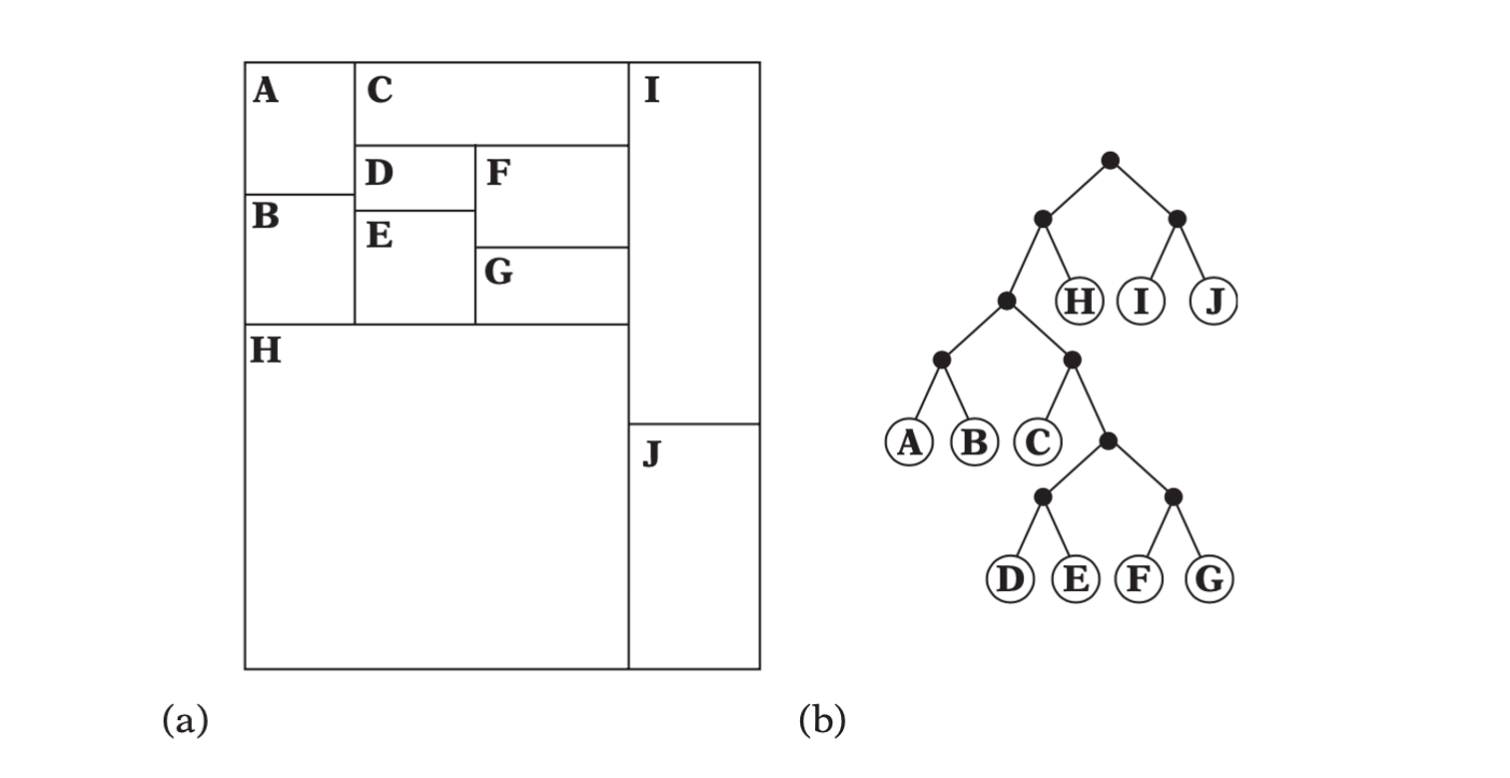

A 2D k-d tree.(a)The spatial decomposition. (b) The k-d tree layout.

Usage of k-d tree

- whenever quadtrees or octrees are used.

- point location (given a point, locate the region it is in).

- nearest neighbor (find the point in a set of points the query point is closed to).

- range search (locate all points within a given region).

struct KDNode { |

Hybrid Schemes

Hybrid schemes are the combination of using different techniques and strategies to divide the scene into multiple layers. For instance, after having initially assigned objects or geometry primitives to a uniform grid, the data in each nonempty grid cell could be further organized in a tree structure.

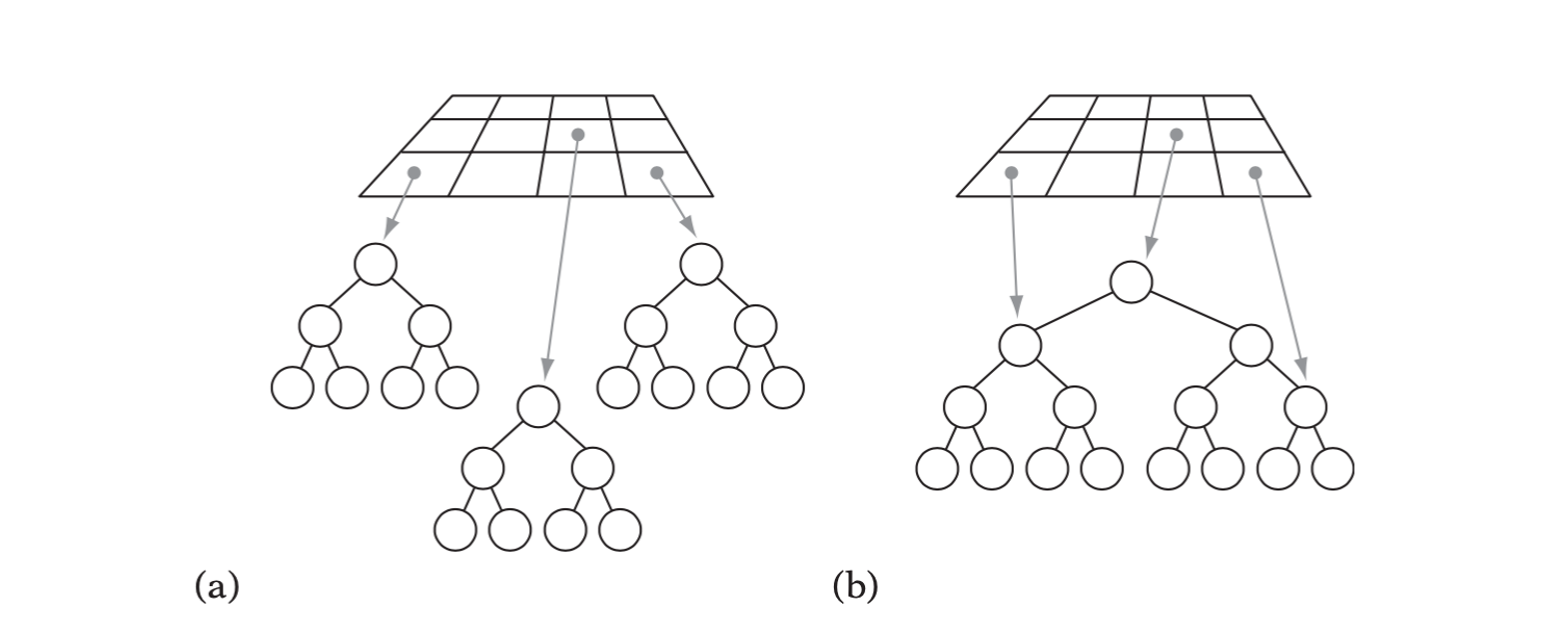

- A grid of trees, each gridcellcontainingaseparatetree.(b)Agridindexing into a single tree hierarchy, each grid cell pointing into the tree at which point traversal should start.

Ray and Directed Line Segment Traversals

Particularly common in many applications, games in particular, are line pick tests. These are queries involving rays or directed line segments.

k-d Tree Intersection Test

The basic idea behind intersecting a ray or directed line segment with a k-d tree is straightforward. The segment \(S(t) = A + t\textbf{d}\) is intersected against the node’s splitting plane, and the \(t\) value of intersection is computed. It \(t\) is within the interval of the segment, \(0 \leq t \leq t_\text{max}\), the segment straddles the plane and both children of the tree are recursively descended.

// Visit all k-d tree nodes intersected by segment S = a + t * d, 0 <= t < tmax |

Uniform Grid Intersection Test

The traversal method used must enforce 6-connectivity of the cells visited along the line. Cells in 3D are said to be 6-connected if they share faces only with other cells. If cells are also allowed to share edges, they are considered 18 connected. A cell is 26-connected if it can share a face, edge, or vertex with another cell.

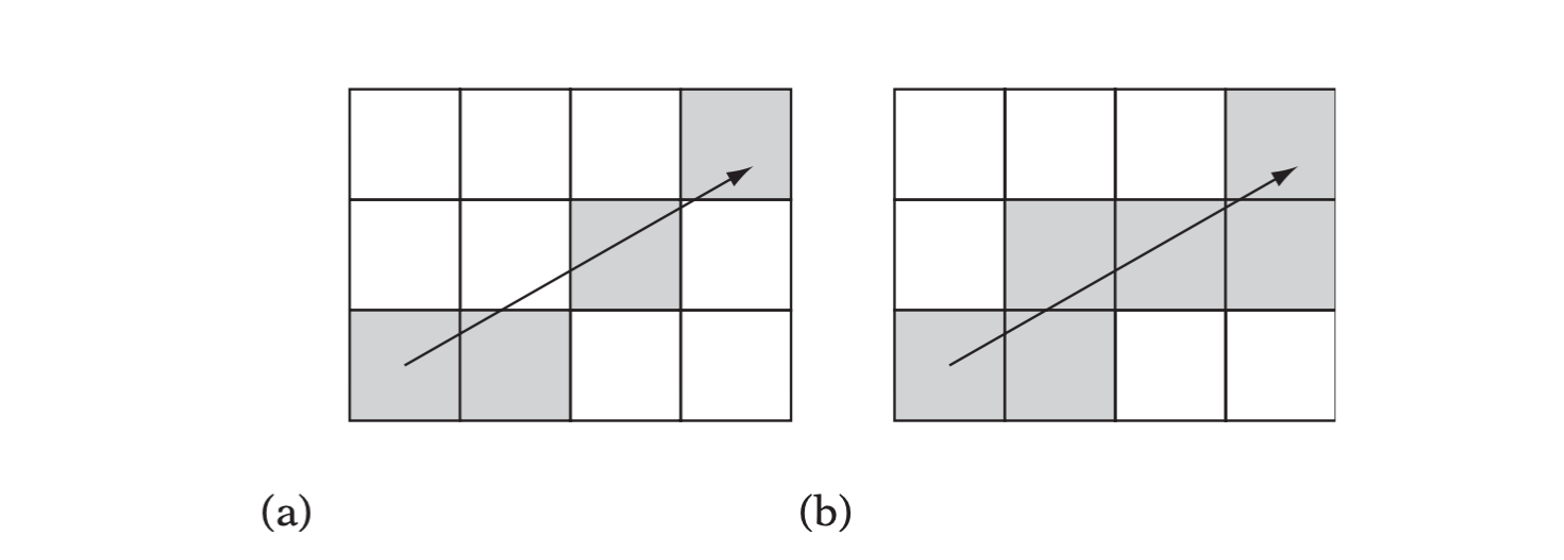

Cell connectivity for a 2D line. (a) An 8-connected line. (b) A 4-connectedline. In 3D, the corresponding lines would be 26-connected and 6-connected, respectively.

Sort and Sweep Methods

A drawback of inserting objects into the fixed spatial subdivisions that grids and octrees represent is having to deal with the added complications of objects straddling multiple partitions. An alternative approach is to instead maintain the objects in some sort of sorted spatial ordering. One way of spatially sorting the objects is the sort and sweep method.

Sorted Linked-list Implementation

To maintain the axis-sorted lists of projection interval extents, two types of structures are required: one that is the linked-list element corresponding to the minimum or maximum interval values and another one to link the two entries.

struct AABB { |

Cells and Portals

This method was developed for rendering architectural walkthrough systems. The cells-and-portals method exploits the occluded nature of these scenes to reduce the amount of geometry that has to be rendered. The method proceeds by dividing the world into regions (cells) and the boundaries that connect them (portals). Rooms in the scene would correspond to cells, and doorways and windows to portals.

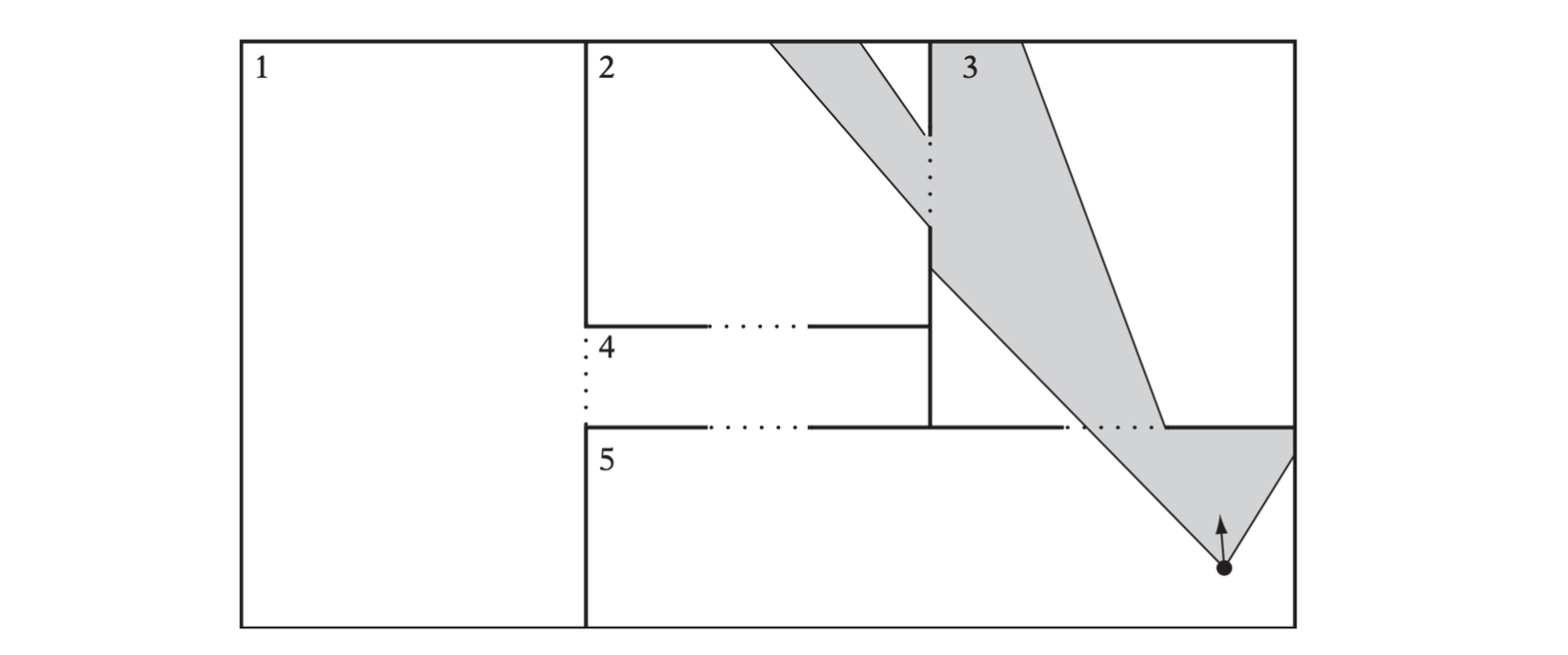

A simple portalized world with five cells (numbered) and five portals (dashed). The shaded region indicates what can be seen from a given viewpoint. Thus, here only cells 2, 3, and 5 must be rendered.

Rendering a scene partitioned into cells and portals starts with drawing the geometry for the cell containing the camera. After this cell has been rendered, the rendering function is called recursively for adjoining cells whose portals are visible to the camera. During recursion, new portals encountered are clipped against the current portal, narrowing the view into the scene. Recursion stops when either the clipped portal becomes empty, or when no unvisited neighboring cells are available.

The following pseudocode illustrates an implementation of this rendering procedure.

RenderCell(ClipRegion r, Cell *c) { |