Basic Primitive Tests

Closest-point Computations

Given the closest points between two objects, the distance between the objects is obtained. If the combined maximum movement of two objects is less than the distance between them, a collision can be ruled out.

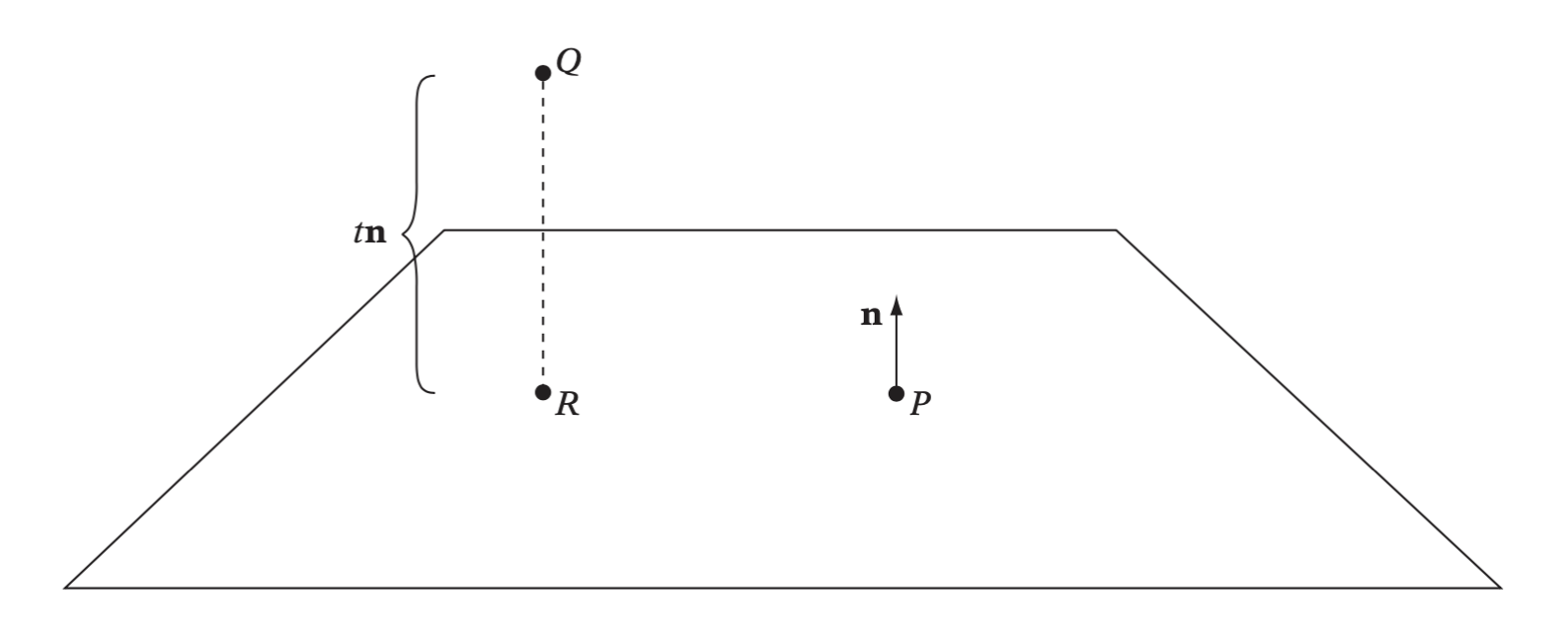

Closest Point on Plane to Point

Given a plane \(\pi\), defined by a point \(P\) and a normal \(\textbf{n}\), all points \(X\) on the plane satisfy the equation \(\textbf{n} \cdot (X - P) = 0\). The closest point on the plane to the given point is \(R\), which is \(R = Q - t\textbf{n}\) for some value \(t\).

Plane π given by P and n. Orthogonal projection of Q onto π gives R, the closest point on π to Q.

Substitute \(R\) into the plane equation gives

\[ R = Q - \frac{\textbf{n} \cdot (Q - P)}{\textbf{n} \cdot \textbf{n}} \textbf{n} \]

When \(\textbf{n}\) is of unit length, \(R\) simplifies to

\[ R = Q - (\textbf{n} \cdot (Q - P))\textbf{n} \]

Closest Point on Line Segment to Point

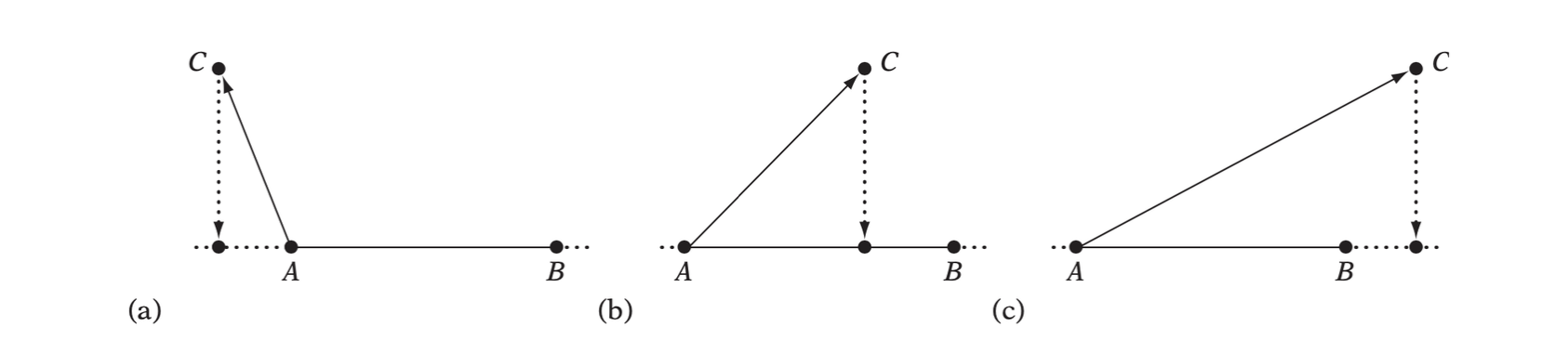

Let \(AB\) be a line segment specified by the endpoint \(A\) and \(B\). Given an arbitrary point \(C\), the problem is to determine the point \(D\) on \(AB\) closest to \(C\).

The three cases of C projecting onto AB: (a) outside AB on side of A, (b) inside AB, and (c) outside AB on side of B.

Any point on the line through \(AB\) can be expressed parametrically as \(P(t) = A + t(B - A)\). The \(t\) corresponding to the projection of \(C\) onto the line is given by \(t = (C - A) \cdot \textbf{n} / \| B - A\|\), where \(\textbf{n} = (B - A) / \|B - A\|\) is a unit vector in the direction of \(AB\) .

Distance of Point to Segment

The squared distance between a point \(C\) and a segment \(AB\) can be directly computed withouth explicitly computing the point \(D\) on \(AB\) closest to \(C\).

When \(AC \cdot AB \leq 0\), \(A\) is closest to \(C\) and the squared distance is given by \(AC \cdot AC\).

When \(AC \cdot AB \geq AB \cdot AB\), \(B\) is closest to \(C\) and the squared distance is given by \(BC \cdot BC\).

When \(0 < AC \cdot AB < AB \cdot AB\), the squared distance is given by \(CD \cdot CD\), where

\[ D = A + \frac{AC \cdot AB}{AB \cdot AB}AB \]

then \(CD \cdot CD\) simplifies to

\[ AC \cdot AC - \frac{(AC \cdot AB)^2}{AB \cdot AB} \]

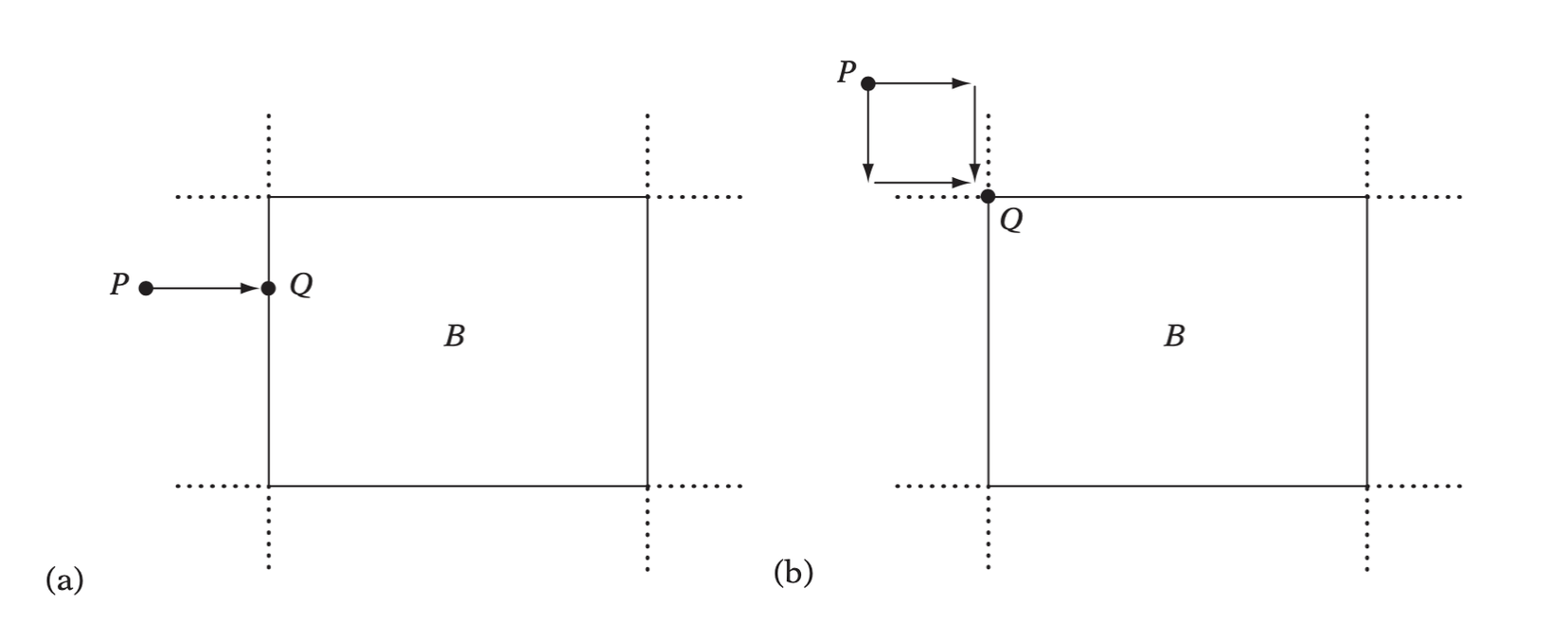

Closest Point on AABB to Point

Let \(B\) be an AABB and \(P\) an arbitrary point in space.

- When \(P\) is inside \(B\), then the clamped point is \(P\) itself.

- When \(P\) is in the Voronoi region of \(B\), the clamping operation will bring \(P\) to that face of \(B\).

- When \(P\) is in the vertex Voronoi region of \(B\), clamping \(P\) gives the vertex as a result.

- When \(P\) is in the edge Voronoi region of \(B\), clamping \(P\) corresponds to an orthogonal projection onto the edge.

Clamping P to the bounds of B gives the closest point Q on B to P: (a) for an edge Voronoi region, (b) for a vertex Voronoi region.

// Given point p, return the point q on or in AABB b that is closest to p |

Distance of Point to AABB

When the point Q on an AABB B closest to a given point P is computed only to determine the distance between P and Q, the distance can be calculated with- out explicitly obtaining Q.

// Computes the square distance between a point p and an AABB b |

Closest Point on Triangle to Point

Given a triangle \(ABC\) and a point \(P\), let \(Q\) describe the point on \(ABC\) closest to \(P\). The better solution to the problem is to compute which of the triangle’s Voronoi feature regions \(P\) is in.

The Voronoi region of vertex A,VR(A), is the intersection of the negative half spaces of the two planes (X – A) · (B – A) = 0 and (X – A) · (C – A) = 0.

The Voronoi region of \(A\) can be determined as the intersection of the negative halfspaces of two planes through \(A\), one with a normal \(B - A\) and the other with the normal \(C - A\).

The Voronoi region of the edge can be obtained by computing the barycentric coordinates of the orthogonal projection \(R\) of \(P\) onto \(ABC\).

Let \(\textbf{n}\) be the normal of \(ABC\) and let \(R = P - t\textbf{n}\) for some \(t\). The barycentric coordinates \((u, v, w)\) of \(R\), \(R = uA + vB + wC\) can then be computed from the quantities listed below.

\[ \textbf{n} = AB \times AC \\ rab = \textbf{n} \cdot (RA \times RB) \\ rbc = \textbf{n} \cdot (RB \times RC) \\ rca = \textbf{n} \cdot (RC \times RA) \\ abc = rab + rbc + rca \\ u = \frac{rbc}{abc}, v = \frac{rca}{abc}, w = \frac{rab}{abc} \]

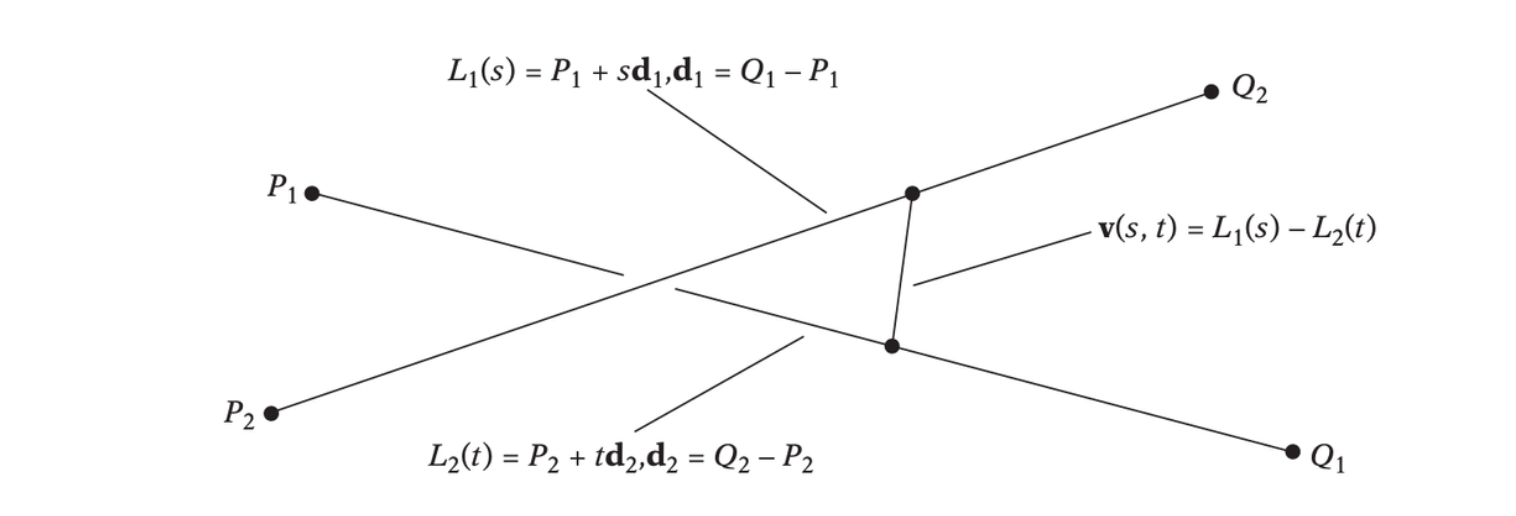

Closest Points of Two Lines

The closest points of two lines can be determined as follows. Let the lines \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) be specified parametrically by the poitns \(P_1\) and \(Q_1\) and \(P_2\) and \(Q_2\):

\[ L_1(s) = P_1 + s\textbf{d}_1, \textbf{d}_1 = Q_1 - P_1 \\ L_2(t) = P_2 + t\textbf{d}_2, \textbf{d}_2 = Q_2 - P_2 \]

For some pair of values for \(s\) and \(t\), \(L_1(s)\) and \(L_2(t)\) correspond to the closest points on the lines, and \(\textbf{v}(s, t) = L_1(s) - L_2(t)\) describes a vector between them.

The vector v(s, t) connecting the two closest points of two lines, L1(s) and L2(t), is always perpendicular to both lines.

Solving the equations

\[ \textbf{d}_1 \cdot \textbf{v}(s, t) = 0 \\ \textbf{d}_2 \cdot \textbf{v}(s, t) = 0 \]

gives

\[ s = (bf - ce)/d \\ t = (af - bc)/d \]

where

\[ \begin{align} \textbf{r} &= P1 - P2 \\ a &= \textbf{d}_1 \cdot \textbf{d}_1 \\ b &= \textbf{d}_1 \cdot \textbf{d}_2 \\ c &= \textbf{d}_1 \cdot \textbf{r} \\ e &= \textbf{d}_2 \cdot \textbf{d}_2 \\ f &= \textbf{d}_2 \cdot \textbf{r} \\ d = ae - b^2 &= (\|\textbf{d}_1\| \|\textbf{d}_1\| \sin(\theta))^2 \end{align} \]

Testing Primitives

The testing of primitives is less general than the computation of distance between them. Generally, a test will indicate only that the primitives are intersectiing, not determine where or how they are intersecting.

Separating-axis Test

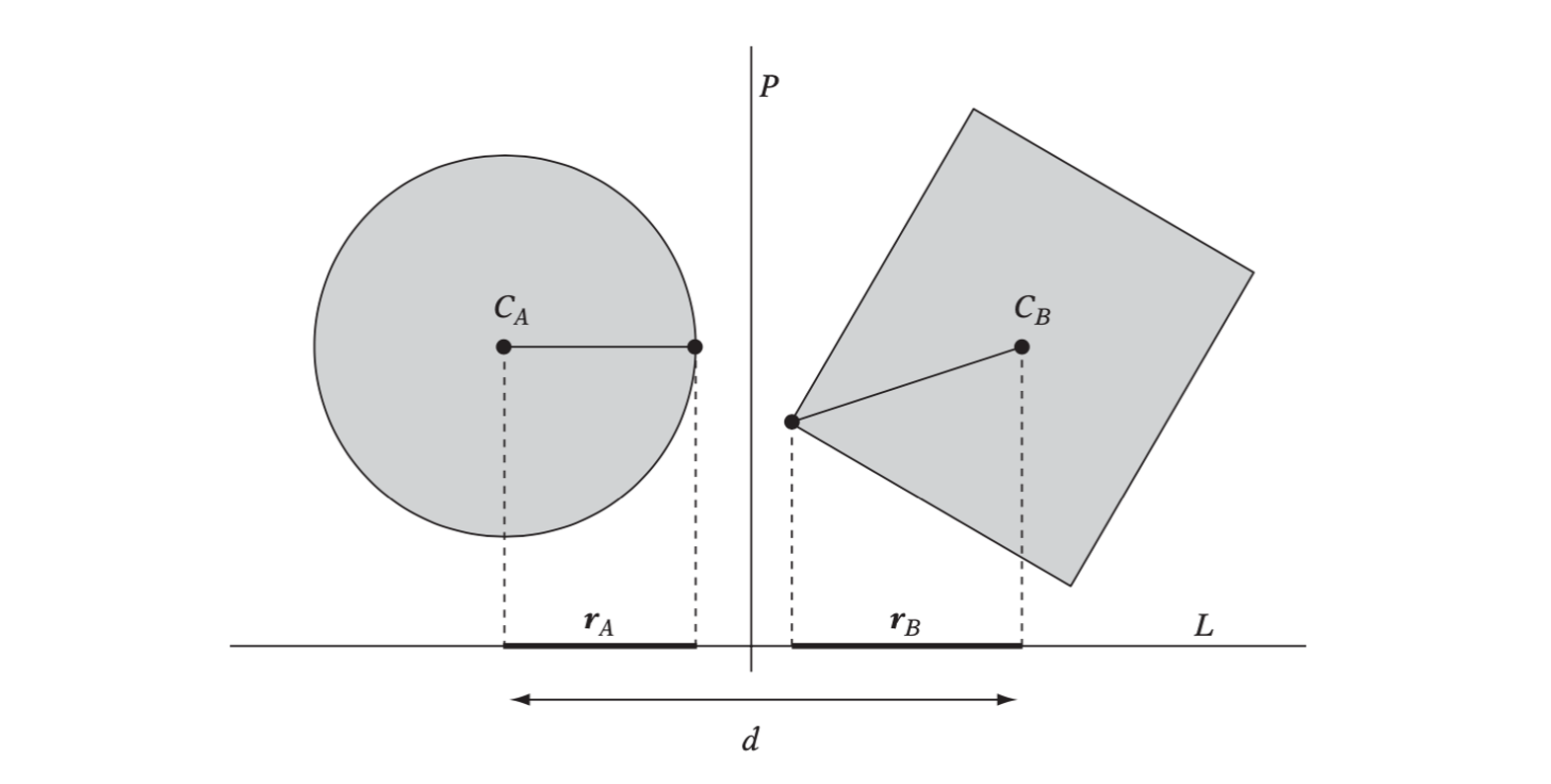

Given a hyperplane \(P\) separating \(A\) and \(B\), a separating axis is a line \(L\) perpendicular to \(P\). It is called a separating axis because the orthogonal projections of \(A\) and \(B\) onto \(L\) result in two nonoverlapping intervals.

Two objects are separated if the sum of the radius (halfwidth) of their projections is less than the distance between their center projections.

To test the separability of two polyhedral objcts the following axes must be tested.

- Axes parallel to face normals of object \(A\).

- Axes parallel to face normals of object \(B\).

- Axes parallel to the vectors resulting from the cross product of all edges in \(A\) with all edges in \(B\).

For two general polytopes with the same number of faces (\(F\)) and edges (\(E\)) there are \(2F + E^2\) potential separating axes.

Testing Sphere Against Plane

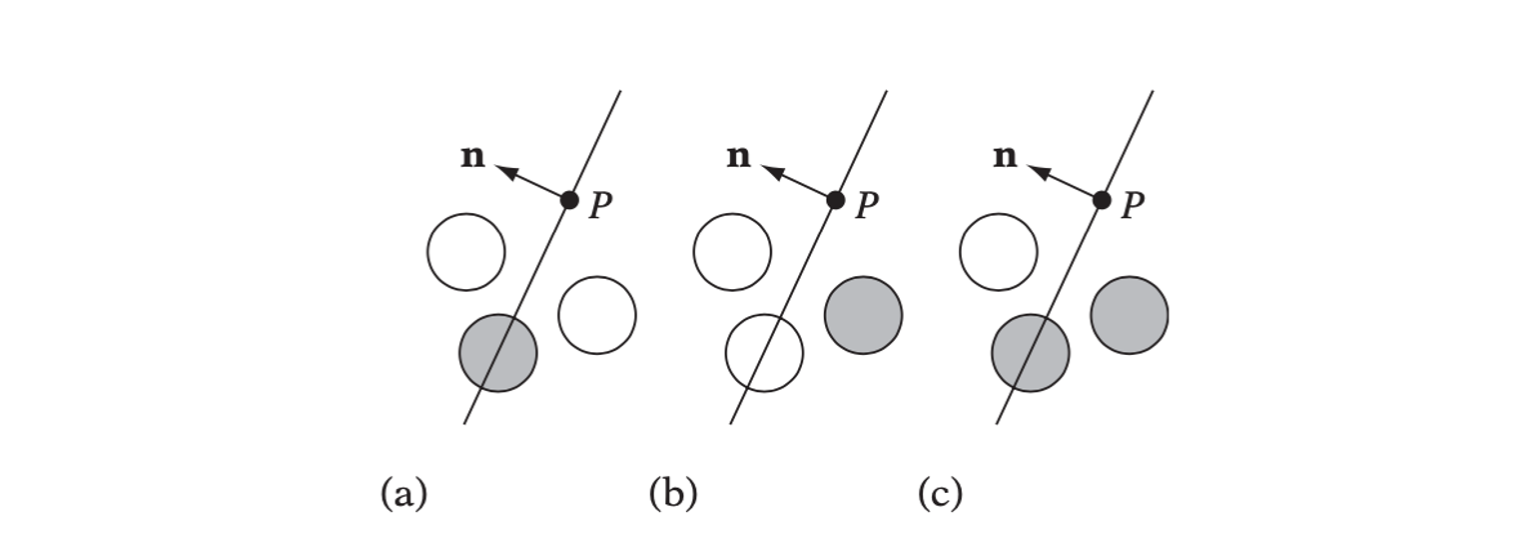

Let a sphere \(S\) be specified by a center position \(C\) and a radius \(r\), and let a plane \(\pi\) be specified by \(\textbf{n} \cdot X = d\), where \(\textbf{n}\) is a unit vector; that is, \(\|\textbf{n}\| = 1\).

Illustrating the three sphere-plane tests. (a) Spheres intersecting the plane. (b) Spheres fully behind the plane. (c) Spheres intersecting the negative halfspace of the plane. Spheres testing true are shown in gray.

Testing Box Against Plane

Testing Sphere Against AABB

Testing whether a sphere intersects an axis-aligned bounding box is best done by computing the distance between the sphere center and the AABB and comparing this distance with the sphere radius.

// Returns true if sphere s intersects AABB b, false otherwise |

Testing Sphere Against Triangle

The point \(P\) on the triangle closest to the sphere center is computed. The distance between \(P\) and the sphere cetner is then compared against the sphere radius to detect possible intersection.

// Returns true if sphere s intersects triangle ABC, false otherwise. |

Testing AABB Agianst Triangle

The test of a triangle \(T\) intersecting a box \(B\) can be efficiently implemented using a separating-axis approach. There are 13 axes that must be considered for projection:

- Three face normals from the AABB.

- One face normal from the triangle.

- Nine axes given by the cross products of combination of edges from both.

It has been suggested that the most efficient order in which to perform these three set of tests is 3-1-2.

The AABB is given by center \(C\), local axes normal vectors \(\textbf{u}_1 = (1, 0, 0), \textbf{u}_2 = (0, 1, 0), \textbf{u}_3 = (0, 0, 1)\) and extends \(e_0, e_1\) and \(e_2\). The triangle is given by three points \(V_0 = (v_{0x}, v_{0y}, v_{0z}), V_1 = (v_{1x}, v_{1y}, v_{1z}), V_2 = (v_{2x}, v_{2y}, v_{2z})\).

- Test the AABB of the triangle and the box.

- Test the box and the plane in which the triangle lies.

- Test the nine axes by the following procedures.

Move the box to the origin and update the triangle correspondingly by \(V_1 = V_1 - C, V_2 = V_2 - C\) and \(V_3 = V_3 - C\).

Calculate the edge of the triangle. \(\textbf{f_0} = V_1 - V_0, \textbf{f}_1 = V_2 - V_1\) and \(\textbf{f}_2 = V_0 - V_2\).

The nine axes can be specified by \(\textbf{a}_{ij} = \textbf{u}_i \times \textbf{f}_j\). Since \(\textbf{u}_i\) is normal, so the axes can be given directly as follows:

\[ \begin{align} \textbf{a}_{00} &= \textbf{u}_0 \times \textbf{f}_0 &= (1, 0, 0) \times \textbf{f}_0 &= (0, -f_{0z}, f_{0y}) \\ \textbf{a}_{01} &= \textbf{u}_0 \times \textbf{f}_1 &= (1, 0, 0) \times \textbf{f}_1 &= (0, -f_{1z}, f_{1y}) \\ \textbf{a}_{02} &= \textbf{u}_0 \times \textbf{f}_2 &= (1, 0, 0) \times \textbf{f}_2 &= (0, -f_{2z}, f_{2y}) \\ \textbf{a}_{10} &= \textbf{u}_1 \times \textbf{f}_0 &= (0, 1, 0) \times \textbf{f}_0 &= (f_{0z}, 0, -f_{0x}) \\ \textbf{a}_{11} &= \textbf{u}_1 \times \textbf{f}_1 &= (0, 1, 0) \times \textbf{f}_1 &= (f_{1z}, 0, -f_{1x}) \\ \textbf{a}_{12} &= \textbf{u}_1 \times \textbf{f}_2 &= (0, 1, 0) \times \textbf{f}_2 &= (f_{2z}, 0, -f_{2x}) \\ \textbf{a}_{20} &= \textbf{u}_2 \times \textbf{f}_0 &= (0, 0, 1) \times \textbf{f}_0 &= (-f_{0y}, f_{0x}, 0) \\ \textbf{a}_{21} &= \textbf{u}_2 \times \textbf{f}_1 &= (0, 0, 1) \times \textbf{f}_1 &= (-f_{1y}, f_{1x}, 0) \\ \textbf{a}_{22} &= \textbf{u}_2 \times \textbf{f}_2 &= (0, 0, 1) \times \textbf{f}_2 &= (-f_{2y}, f_{2x}, 0) \end{align} \]

The projection of a box with respect to an axis \(\textbf{n}\) is given by

\[ r = e_0|\textbf{u}_0 \cdot \textbf{n}| + e_1|\textbf{u}_1 \cdot \textbf{n}| + e_2|\textbf{u}_2 \cdot \textbf{n}| \]

The projection of a triangle onto an axis \(\textbf{n}\) results in the projection interval \([\min(p_0, p_1, p_2), \max(p_0, p_1, p_2)]\), where \(p_0, p_1\) and \(p_2\) are the distances from the origin to the projections of the triangle vertices onto \(\textbf{n}\).

If the projection intervals \([-r, r]\) and \([\min(p_0, p_1, p_2), \max(p_0, p_1, p_2)]\) are disjoint for the given axis, namely \(\max(-\max(p_i, p_j), \min(p_i, p_j)) > r\), the axis is a separating axis and the triangle and the AABB do not overlap.

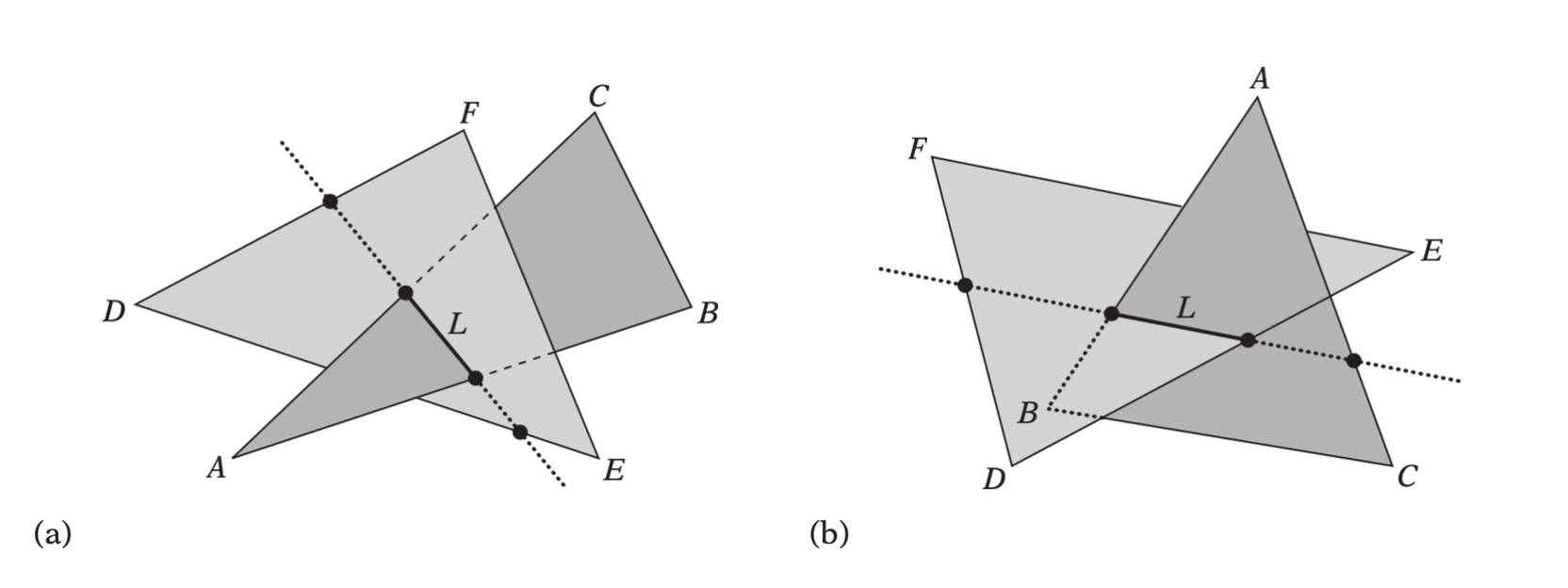

Testing Triangle Against Triangle

The most straightforward test is based on the fact that in general when two triangles intersect either two edges of one triangle pierce the interior of the other or one edge from each triangle pierces the interior of the other triangle.

In the general case,two triangles intersect (a) when two edges of one triangle pierce the interior of the other or (b) when one edge from each pierces the interior of the other.

Intersecting Lines, Rays, and (Directed) Segments

Intersecting Segment Against Plane

The plane is given by \((\textbf{n} \cdot X) = d\) and the segment is given by \(S(t) = A + t(B - A)\) for \(t \in [0, 1]\). Substituting the segment equation into the plane equation, we get

\[ (\textbf{n} \cdot (A + t(B - A)))= d \]

Solving for \(t\) gives

\[ t = \frac{d - \textbf{n} \cdot A}{\textbf{n} \cdot (B - A)} \]

Sustitute \(t\) into the segment equation to obtain the intersection point.

Intersecting Ray or Segment Against Sphere

The ray is given by \(R(t) = P + t\textbf{d}\), where \(t > 0\), \(P\) is the ray origin and \(\textbf{d}\) a normalized direction vector. The sphere is given by \((X - C)\cdot(X - C) = r^2\). To find the intersection point, substitute \(R(t)\) into the sphere equation, gives

\[ (P + t \textbf{d} - C) \cdot (P + t \textbf{d} - C) = r^2 \]

Let \(\textbf{m} = P - C\), then the above equation can be formalized into the following quadratic equation,

\[ t^2 + 2(\textbf{m} \cdot \textbf{d})t + (\textbf{m}\cdot\textbf{m}) - r^2 = 0 \]

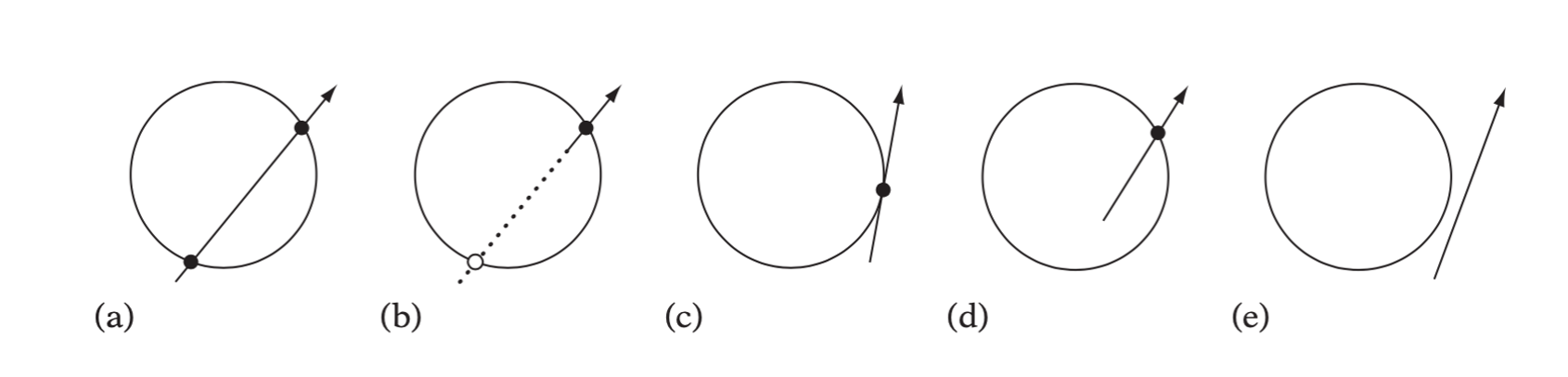

the solution is given by \(t = -b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - c}\). There are three cases of the solution.

- if \(b^2 - c < 0\), then the ray missing the sphere completely.

- if \(b^2 = c\), then the ray is hitting the sphere tengentially in a point.

- if \(b^2 - c > 0\), then the ray enters the sphere and then leaves it.

Different cases of ray-sphere intersection: (a) ray intersects sphere (twice) with t > 0, (b) false intersection with t < 0, (c) ray intersects sphere tangentially, (d) ray starts inside sphere, and (e) no intersection.

Intersection Ray or Segment Against Box

A test for intersecting a ray against a box therefore only needs to compute the intersection intervals of the ray wih the planes of the slabs and perform some simple comparison operations to maintain the logical intersection of all intersection intervals along the ray.

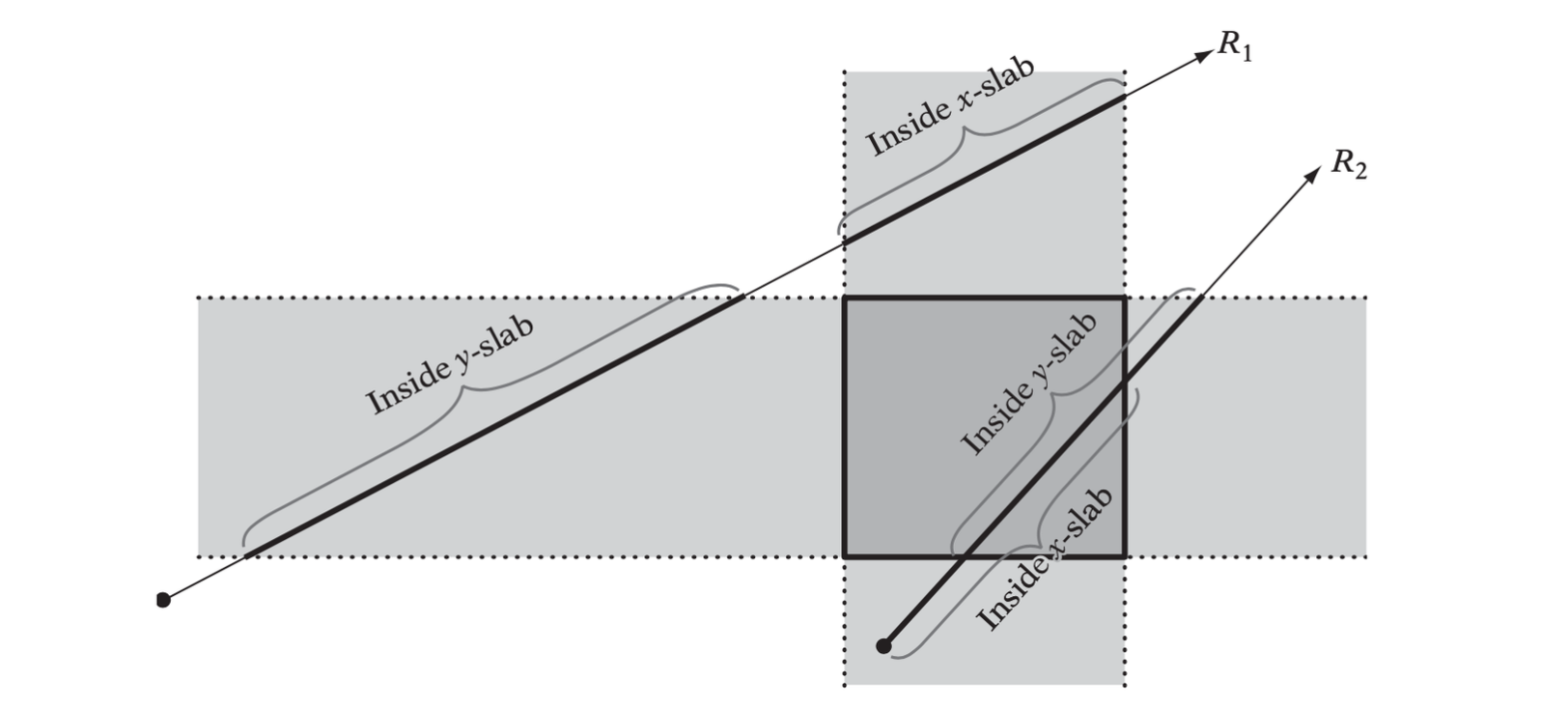

Ray R1 does not intersect the box because its intersections with the x slab and the y slab do not overlap. Ray R2 does intersect the box because the slab intersections overlap.

The ray is given by \(R(t) = P + t\textbf{d}\), the slab planes are given by \(X \cdot \textbf{n}_i = d_i\). Solving for \(t\) gives \(t = (d - P \cdot \textbf{n}_i) / (\textbf{d} \cdot \textbf{n}_i)\).

Intersecting Line Against Triangle

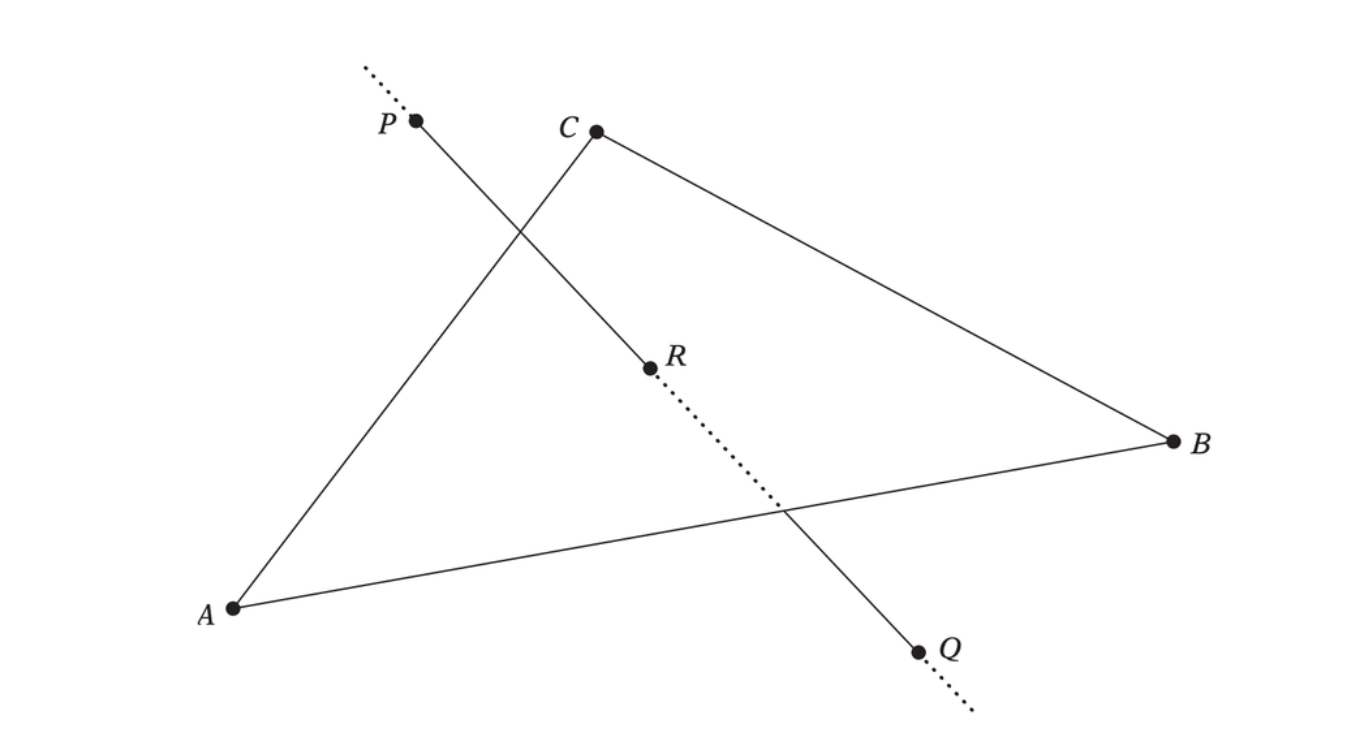

Given a triangle \(ABC\) and a line through \(PQ\). The line \(PQ\) intersects \(ABC\) if the point \(R\) of intersection between the line and the plane of \(ABC\) lies inside the triangle.

Intersecting the line through P and Q against the triangle ABC.

Consider three scalar products

\[ u = [PQ \ PC \ PB] \\ v = [PQ \ PA \ PC] \\ w = [PQ \ PB \ PA] \]

If \(ABC\) is counterclockwise, for \(PQ\) to pass to the left of the edges \(BC, CA\) and \(AB\) the expressions \(u \geq 0, v \geq 0\) and \(w \geq 0\) must be true.

For obtaining the intersection point with \(ABC\), it can be shown that \(u, v, w\) are proportional to \(u^*, v^*, w^*\):

\[ u^* = ku = [PQ \ PC \ PB] \\ v^* = kv = [PQ \ PA \ PC] \\ w^* = kw = [PQ \ PB \ PA] \]

where \(k = \|PR\|/\|PQ\|\).

Intersecting Ray or Segment Against Triangle

Let a directed line segment between the two points \(P\) and \(Q\) be defined parametrically as \(R(t) = P+ t(Q - P), 0 \leq t \leq 1\). And the triangle be given by \(T(u, v, w) = uA + vB + wC\). Rearrange it with \(u = 1 - v - w\) gives \(T(v, w) = A + v(B - A) + w(C - A)\). Finding the intersection point is the same as solving the following equation.

\[ T(v, w) = R(t) \iff \\ (P - Q)t + (B - A)v + (C - A)w = P - A \]

In matrix notion

\[ \begin{bmatrix} (P - Q) & (B - A) & (C - A) \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} t \\ v \\ w \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} (P - A) \end{bmatrix} \]

Solving the equation gives

\[ \begin{align} t &= (P - A) \cdot \textbf{n} / d \\ v &= (C - A) \cdot \textbf{e} / d \\ w &= -(B - A) \cdot \textbf{e} / d \\ \end{align} \]

where

\[ \begin{aligned} \textbf{n} &= (B - A) \times (C - A) \\ d &= (P - Q) \cdot \textbf{n} \\ \textbf{e} &= (P - Q) \times (P - A) \end{aligned} \]

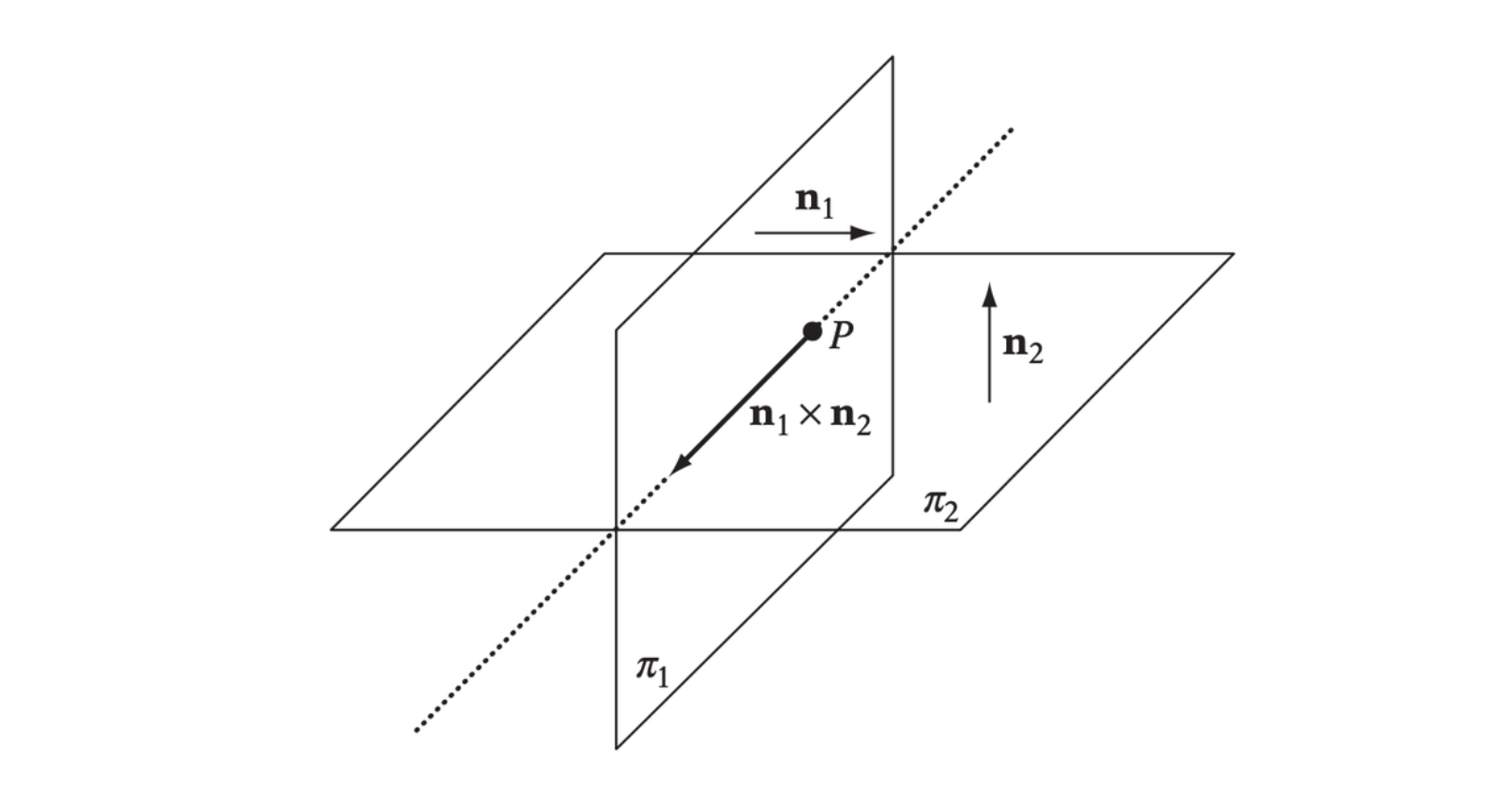

Intersection of Two Planes

Let two planes \(\pi_1\) and \(\pi_2\) given by equations \(\textbf{n}_1 \cdot X = d_1\) and \(\textbf{n}_2 \cdot X = d_2\). Then the planes are not parallel, they intersect in a line \(L = P + t\textbf{d}\). Since \(L\) lies in both of the planes, it must be perpendicular to the normals of both planes, so \(\textbf{d} = \textbf{n}_1 \times \textbf{n}_2\). If \(\textbf{d}\) is a zero vector, then the planes are parallel or coincident.

Since the point \(P\) can be spaned by \(\textbf{n}_1\) and \(\textbf{n}_2\), so we have the following equations

\[ \textbf{n}_1 \cdot (k_1 \textbf{n}_1 + k_2 \textbf{n}_2) = d_1 \\ \textbf{n}_2 \cdot (k_1 \textbf{n}_1 + k_2 \textbf{n}_2) = d_2 \]

Expanding the dot product gives

\[ k_1 (\textbf{n}_1 \cdot \textbf{n}_1) + k_2 (\textbf{n}_1 \cdot \textbf{n}_2) = d_1 \\ k_1 (\textbf{n}_1 \cdot \textbf{n}_2) + k_2 (\textbf{n}_2 \cdot \textbf{n}_2) = d_2 \]

Solving with Cramer’s rule to give the solution.

\[ k_1 = \frac{d_1(\textbf{n}_2 \cdot \textbf{n}_2) - d_2(\textbf{n}_1 \cdot \textbf{n}_2)}{denom} \\ k_2 = \frac{d_2(\textbf{n}_1 \cdot \textbf{n}_1) - d_1(\textbf{n}_1 \cdot \textbf{n}_2)}{denom} \]

where

\[ \begin{align} denom &= (\textbf{n}_1 \cdot \textbf{n}_1)(\textbf{n}_2 \cdot \textbf{n}_2) - (\textbf{n}_1 \cdot \textbf{n}_2)^2 \\ &= (\textbf{n}_1 \times \textbf{n}_2) \cdot (\textbf{n}_1 \times \textbf{n}_2) \\ &= \textbf{d} \cdot \textbf{d} \end{align} \]

And finally the point \(P\) is given by

\[ P = (d_1 \textbf{n}_2 - d_2 \textbf{n}_1) \times \textbf{d} / (\textbf{d} \cdot \textbf{d}) \\ \textbf{d} = \textbf{n}_1 \times \textbf{n}_2 \]

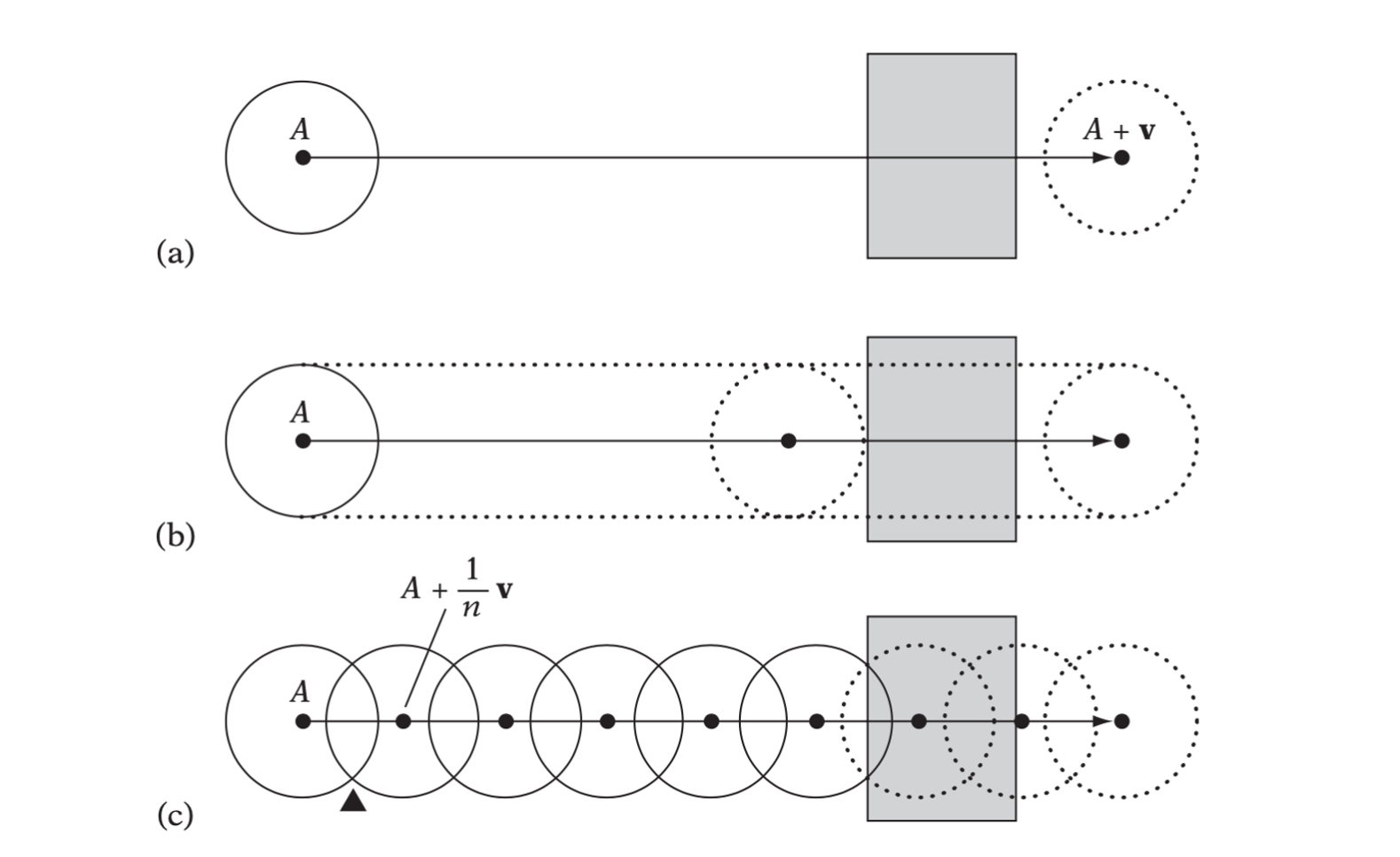

Dynamic Intersection Tests

A problem with static testing is that as the object movement increases between one point in time and the next so does the likelihood of an object simply jumping past another object. This unwanted phenomenon is called tunneling.

Dynamic collision tests. (a) Testing only at the start point and endpoint of an object’s movement suffers from tunneling. (b) A swept test finds the exact point of collision, but may not be possible to compute for all objects and movements. (c) Sampled motion may require a lot of tests and still exhibit tunneling in the region indicated by the black triangle.

Continuous swept test is expensive and complicated for most of the real-time application. A compromise is to sample the path of the object and perform several static object tests during a single object ovement.

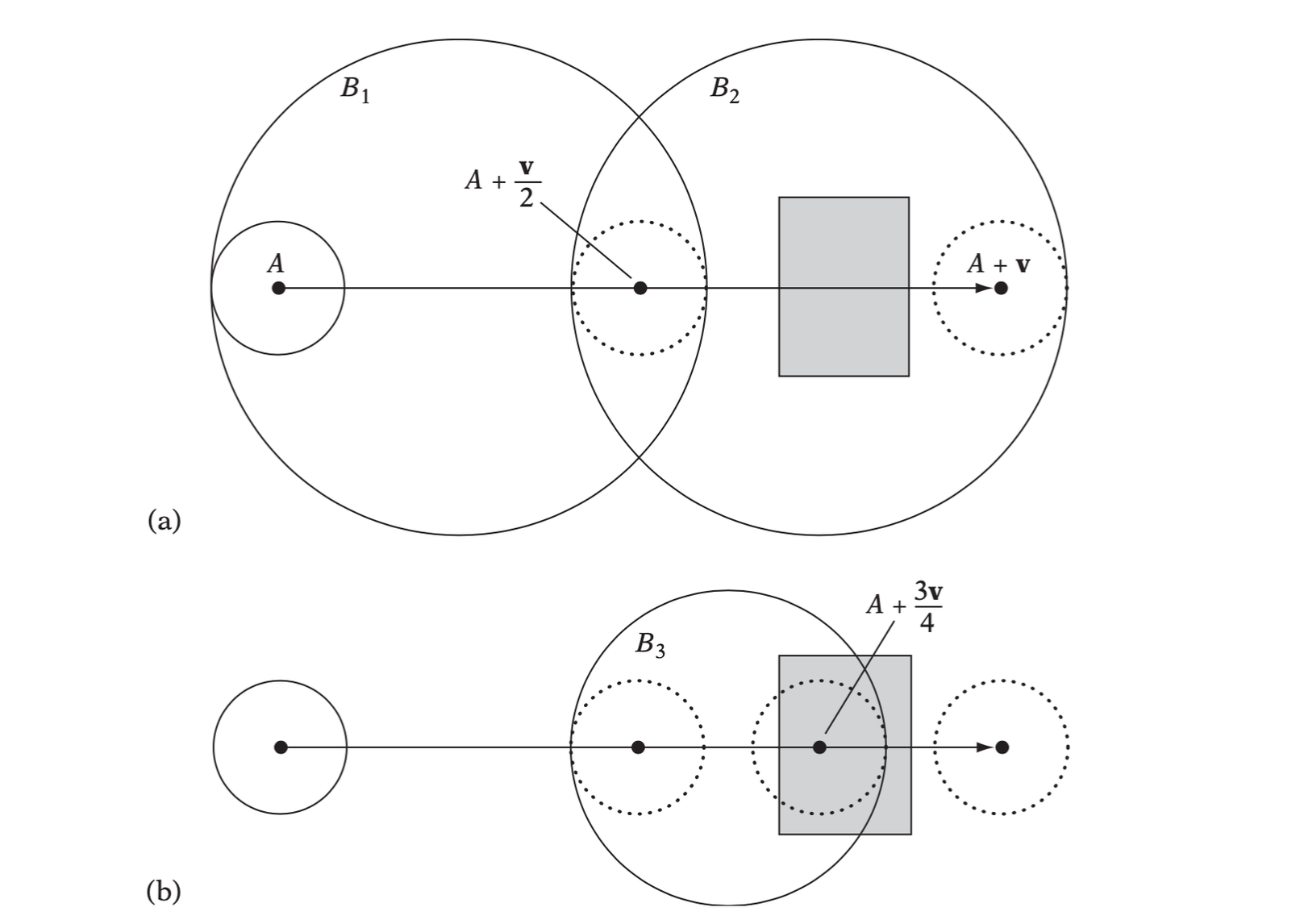

Interval Halving for Intersecting Moving Objects

Somewhere halfway between the sampling method and performing a contnuous swept test lies a method based on performing a recursive binary search over the object movement to find the time of collision, if any.

A few steps of determining the collision of a moving sphere against a stationary object using an interval-halving method.

// Intersect sphere s0 moving in direction d over time interval t0 <= t <= t1, against |