Clean Architecture

When software is done right, it requires a fraction of the human resources to create and maintain. Changes are simple and rapid. Defects are few and far between. Effort is minimized, and functionality and flexibility are maximized.

The goal of software architecture is to minimize the human resources required to build and maintain the required system. The measure of design quality is simply the measure of the effort required to meet the needs of the customer. If that effort is low, and stays low throughout the lifetime of the system, the design is good. If the effort grows with each new release, the design is bad. It's as simple as that.

The only way to go fast, is to go well.

Behavior and Structure

Every software system provides two different values to the stakeholders: behavior and structure.

The dilemma for software developers is that business managers are not equipped to evaluate the importance of architecture. That's what software developers were hired to do. Therefore it is the responsibility of the software development team to assert the importance of architecture over the urgency of features.

Software architects are, by virtue of their job description, more focused on the structure of the system than on its features and functions. Architects create an architecture that allows those features and functions to be easily developed, easily modified, and easily extended.

Software has two types of value: the value of its behavior and the value of its structure. The second of these is the greater of the two because it is this value that makes software soft.

3 Main Paradigms

Structure programming, object-oriented programming and functional programming.

- Structure programming imposes discipline on direct transfer of control.

- Object-oriented programming imposes discipline on indirect transfer of control.

- Functional programming imposes discipline upon assignment.

We use polymorphism as the mechanism to cross architectural boundaries; we use functional programming to impose discipline on the location of and access to data; and we use structured programming as the algorithmic foundation of our modules.

Software development is not a mathematical endeavor, even though it seems to manipulate mathematical constructs. Rather, software is like a science. We show correctness by failing to prove incorrectness, despite our best efforts.

Software is like a science and, therefore, is driven by falsifiability.

Immutability and Architecture

All race conditions, deadlock conditions, and concurrent update problems are due to mutable variables. You cannot have a race condition or a concurrent update problem if no variable is ever updated. You cannot have deadlocks without mutable locks.

Design Principles

The goal of the principles is the creation of mid-level software structures that:

- Tolerate change,

- Are easy to understand, and

- Are the basis of components that can be used in many software systems.

SOLID Principles

SRP: The Single Responsibility Principle

A module should have one, and only one, reason to change.

Software systems are changed to satisfy users and stakeholders; those users and stakeholders are the "reason to change" that the principle is talking about. Indeed, we can rephrase the principle to say this:

A module should be responsible to one, and only one, user or stakeholder (or actor).

OCP: The Open-Closed Principle

A software artifact should be open for extension but closed for modification.

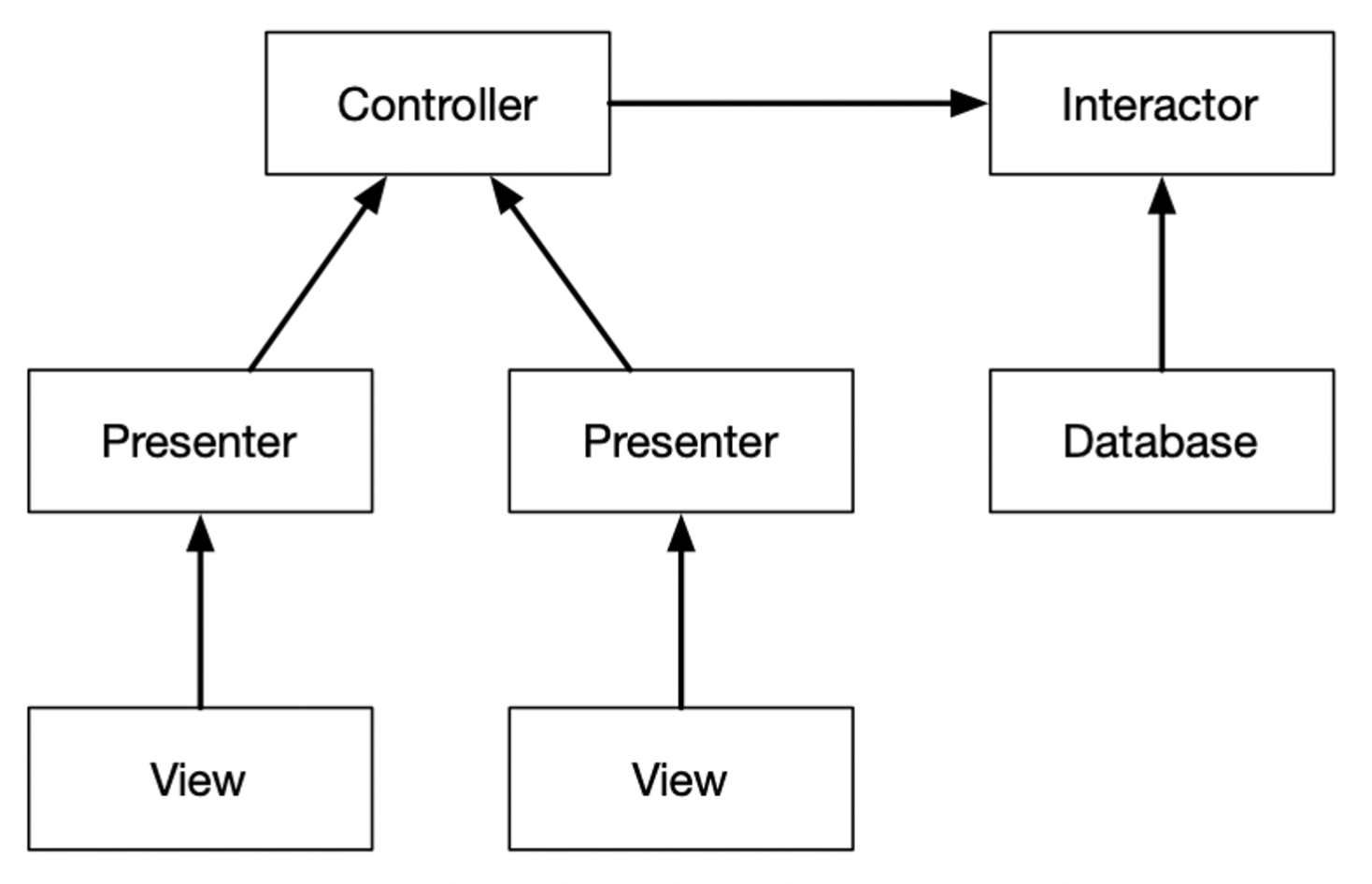

Protection priority of different types of components inside a system.

Interactor → Controller → Presenter → Views

Interactors are the highest-level concept, so they are the most protected. Views are among the lowest-level concepts, so they are the least protected.

LSP: The Liskov Substitution Principle

What is wanted here is something like the following substitution property: If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2 then S is a subtype of T. — Liskov

ISP: The Interface Segregation Principle

In general, it is harmful to depend on modules that contain more than you need.

DIP: The Dependency Inversion Principle

The most flexible systems are those in which source code dependencies refer only to abstractions, not to concretions.

Good software designers and architects work hard to reduce the volatility of interfaces. They try to find ways to add functionality to implementations without making changes to the interfaces. This is Software Design 101.

Component Cohesion

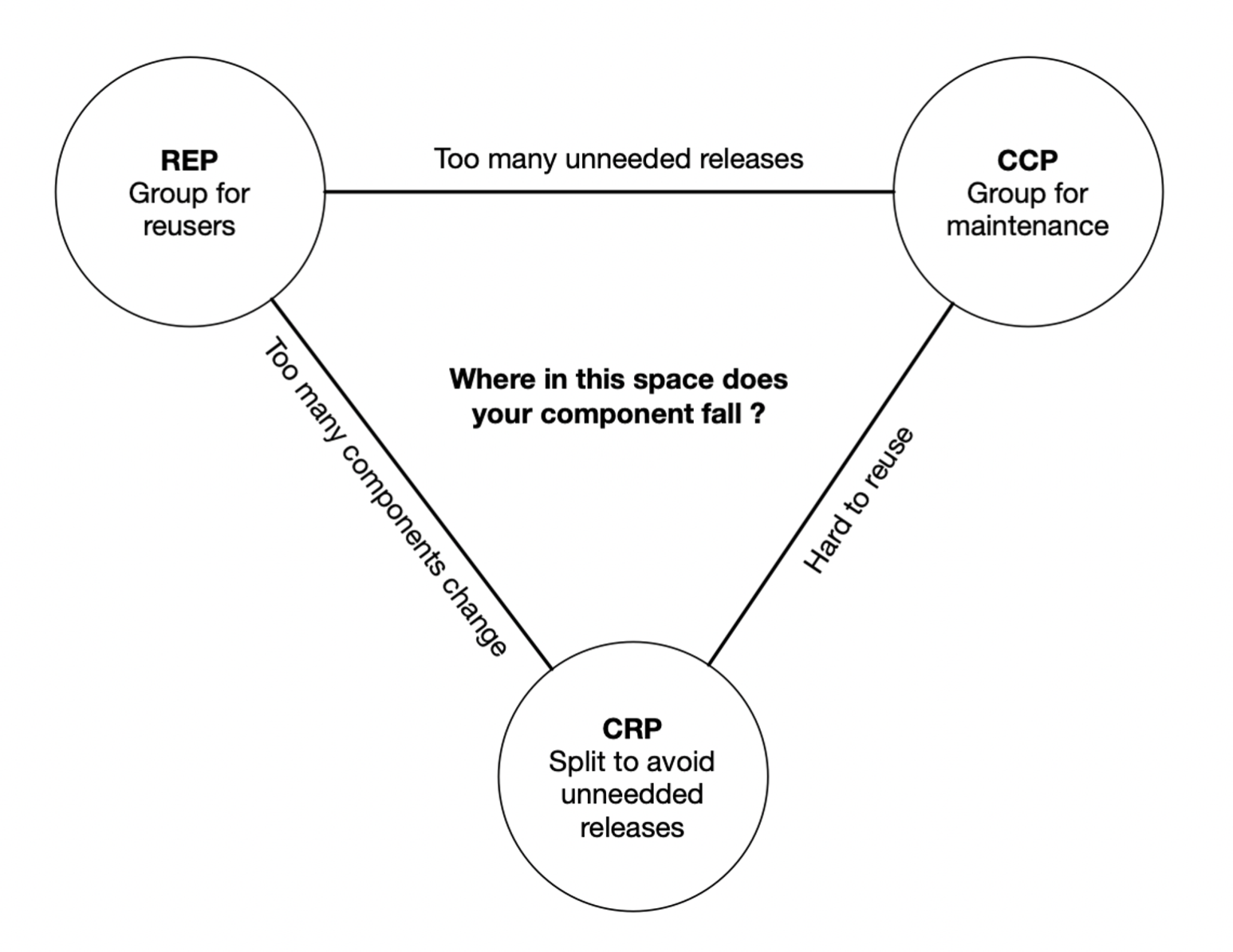

REP: The Reuse/Release Equivalence Principle

The granule of reuse is the granule of release.

CCP: The Common Closure Principle

Gather into components those classes that change for the same reasons and at the same times. Separate into different components those classes that change at different times and for different reasons.

CRP: The Common Reuse Principle

Don't force users of a component to depend on things they don't need.

Component Coupling

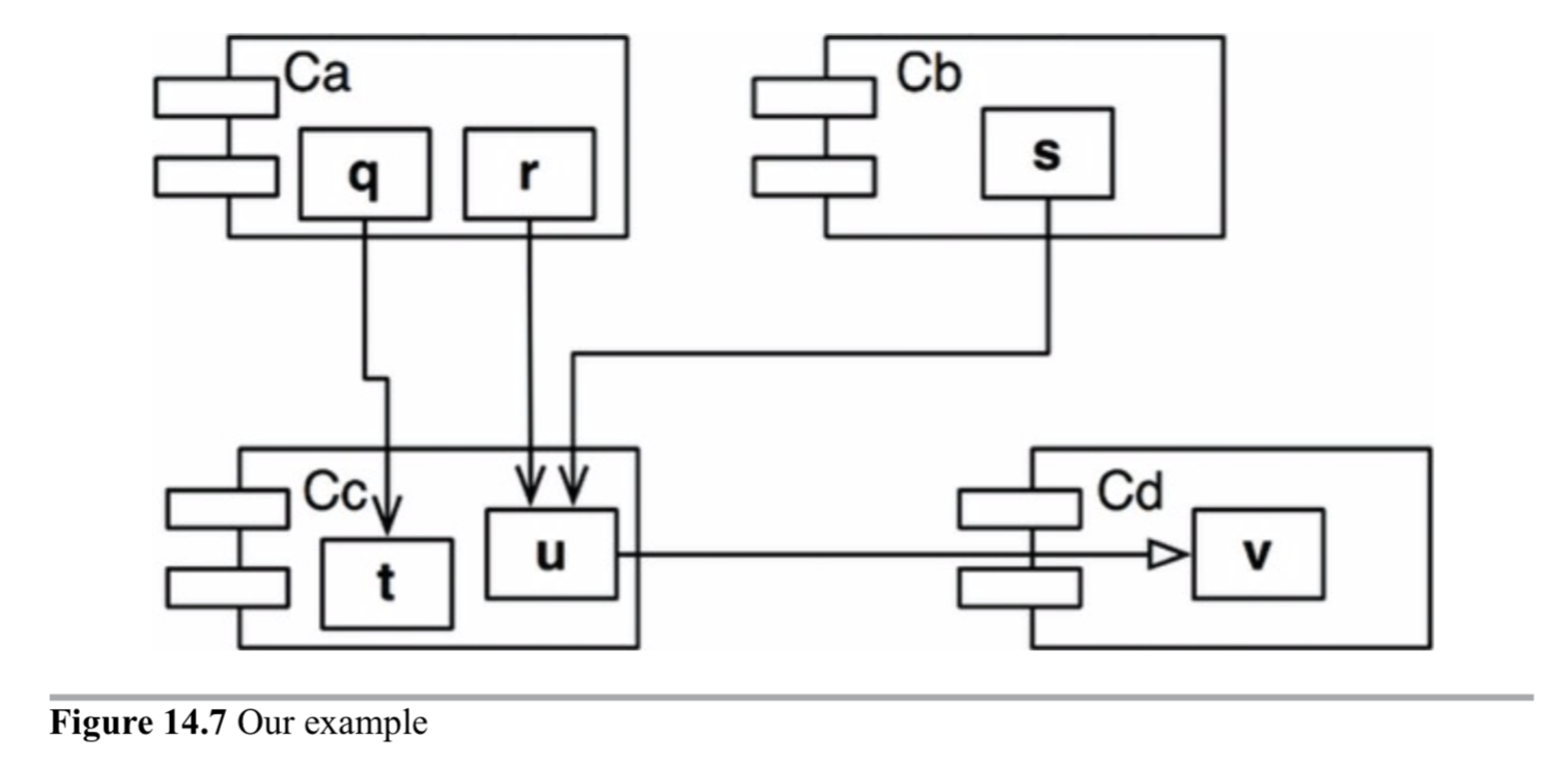

The ADP (Acyclic Dependencies Principle)

Allow no cycles in the component dependency graph.

The Weekly Build

The weekly build used to be common in medium-sized projects. It works like this: All the developers ignore each other for the first four days of the week. They all work on private copies of the code, and don't worry about integrating their work on a collective basis. Then on Friday, they integrate all their changes and build the system.

The SDP (Stable Dependencies Principle)

Depend in the direction of stability.

Stability is related to the amount of work required to make a change.

Stability Metrics

- \[\text{Fan-in}\]: Incoming dependencies. This metric identifies the number of classes outside this component that depend on classes within the component.

- \[\text{Fan-out}\]: Outgoing dependencies. This metric identifies the number of classes inside this component that depend on classes outside the component.

- \[I\]: Instability: \[I = \text{Fan-out} / (\text{Fan-in} + \text{Fan-out})\]. This metric has the range \[[0, 1]\]. \[I = 0\] indicates a maximally stable component. \[I = 1\] indicates a maximally unstable component.

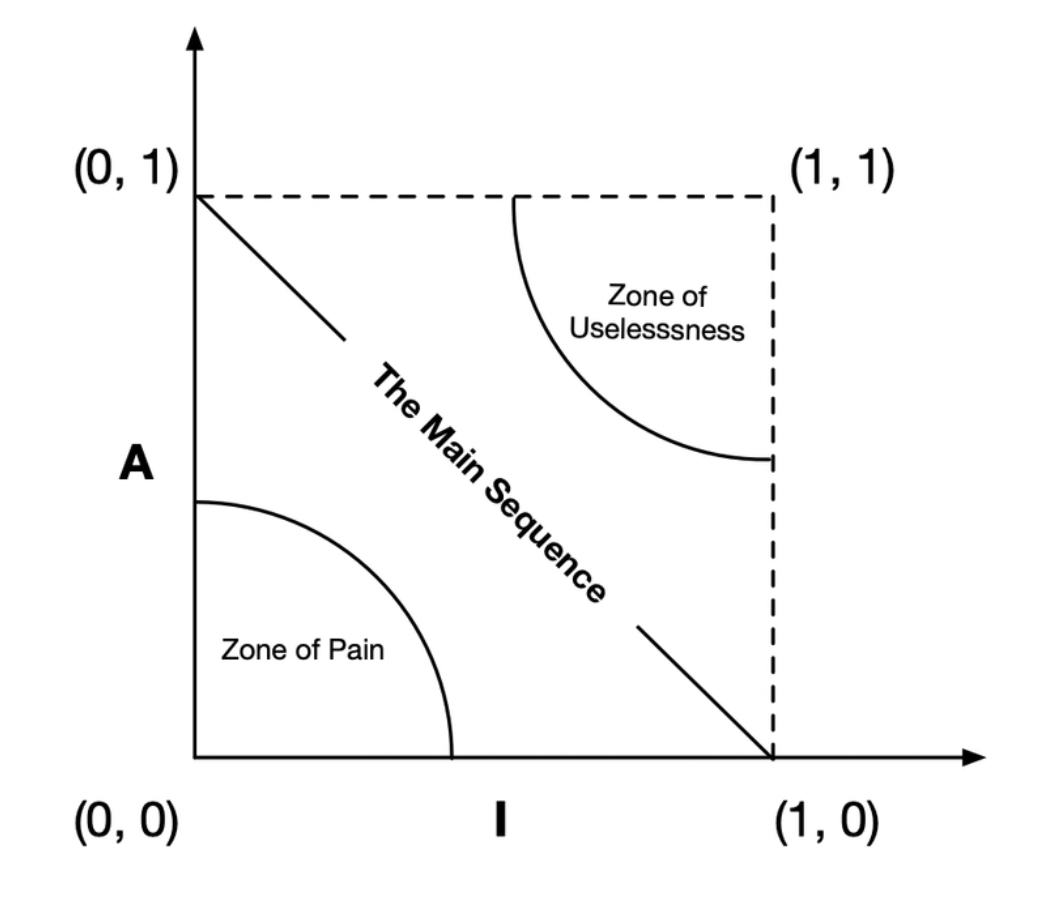

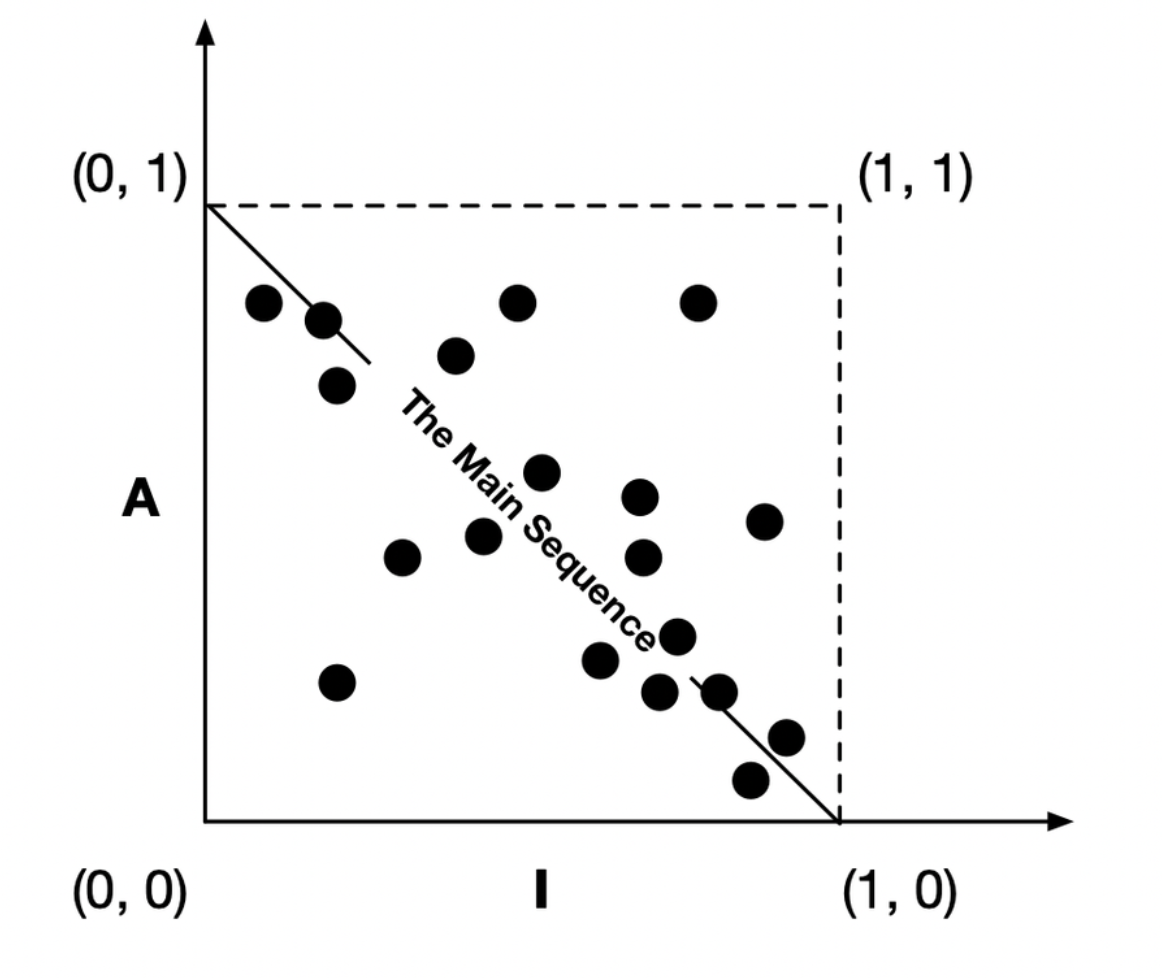

The SAP (Stable Abstractions Principle)

A component should be as abstract as it is stable.

- \[N_c\]: The number of classes in the component.

- \[N_a\]: The number of abstract classes and interfaces in the component.

- \[A\]: Abstractness. \[A = N_a / N_c\].

Some software entities do, in fact, fall within the Zone of Pain. An example would be a database schema. Database schemas are notoriously volatile, extremely concrete, and highly depended on. This is one reason why the interface between OO applications and databases is so difficult to manage, and why schema updates are generally painful.

Distance from the main sequence

- \[D\]: Distance. \[D = \|A + I - 1\|\]. The range of this metric is \[[0, 1]\].

In such a way, statistical analysis of a design is also possible. We can calculate the mean and variance of all the \[D\] metrics for the components within a design. We would expect a conforming design to have a mean and variance that are close to zero. The variance can be used to establish "control limits" so as to identify components that are "exceptional" in comparison to all the others.

Architecture

The architecture of a software system is the shape given to that system by those who build it. The form of that shape is in the division of that system into components, the arrangement of those components, and the ways in which those components communicate with each other.

The purpose of that shape is to facilitate the development, deployment, operation, and maintenance of the software system contained within it.

The strategy behind that facilitation is to leave as many options open as possible, for as long as possible.

Development

A software system that is hard to develop is not likely to have a long and healthy lifetime. So the architecture of a system should make easy to develop, for the team who develop it.

Deployment

To be effective, a software system must be deployable. The higher the cost of deployment, the less useful the system is. A goal of a software architecture, then, should be to make a system that can be easily deployed with a single action.

Operation

The impact of architecture on system operations tends to be dramatic than the impact of architecture on development, deployment, and maintenance. Almost any operational difficulty can be resolved by throwing more hardware at the system without drastically impacting the software architecture.

Maintenance

A carefully though-through architecture vastly mitigates the cost of iteration and bug fixing. By separating the system into components, and isolating those components through stable interfaces, it is possible to illuminate the pathways for future features and greatly reduce the risk of inadvertent breakage.

Keeping Options Open

The way to keep software soft is to leave as many options open ass possible, for as long as possible. What are the options that we need to leave open? They are the details that don't matter. Such as IO devices, databases, web systems, servers, frameworks, communication protocols, and so forth.

The longer you leave options open, the more experiments you can run, the more things you can try, and the more information you will have when you reach the point at which those decisions can no longer be deferred.

A good architect pretends that the decision has not been made, and shapes the system such that those decisions can still be deferred or changed for as long as possible.

In a word: A good architect maximizes the number of decisions not made.

Independance

Decoupling layers

Decoupling use cases

If you decouple the elements of the system that change for different reasons, then you can continue to add new use cases without interfering with old ones. If you also group the UI and database in support of those use cases, so that each use case uses a group the UI and database in support of those use cases, so that each use case uses a different aspect of the UI and database, then adding new sue cases will be unlikely to affect older ones.

Independent develop-ability

Independent deployability

Duplication

Architects often fall into a trap — a trap that hinges on their fear of duplication.

But there are different kinds of duplication. There is true duplication, in which every change to one instance necessitates the same change to every duplicate of that instance. If two apparently duplicated sections of code evolve along different paths — if they change at different rates, and for different reasons — then they are not true duplicates.

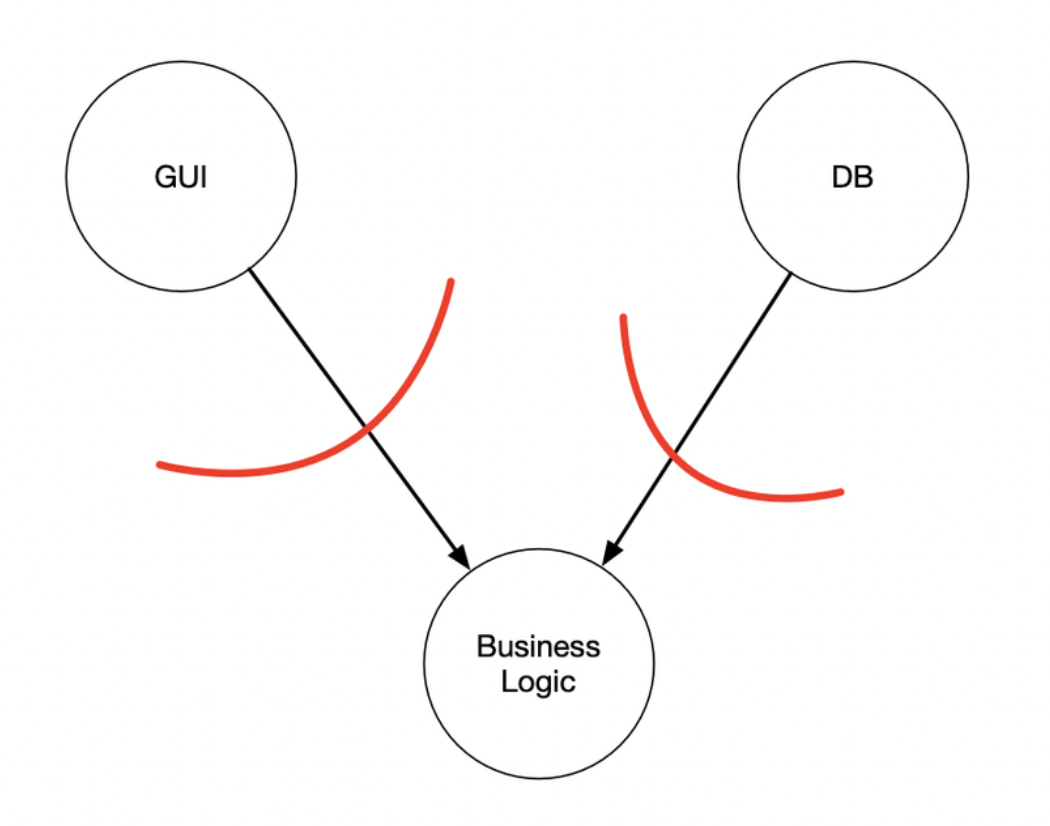

Bounderies

Which kinds of decisions are premature? Decisions that have nothing to do with the business requirements — the use cases — of the system. These include decisions about frameworks, databases, web servers, utility libraries, dependency injection, and the like. A good system architecture is one in which decisions like these are rendered ancillary and deferrable. A good system architecture does not depend on those decisions. A good system architecture allows those decisions to be made at the latest possible moment, without significant impact.

Policy and Level

Policy

Software systems are statements of policy. Indeed, at its core, that's all a computer program actually is. A computer program is a detailed description of the policy by which inputs are transformed into outputs.

Level

A strict definition of "level" is "the distance from the inputs and outputs."

Policies are grouped into components based on the way that they change. Policies that change for the same reasons and at the same times are grouped together by the SRP and CCP. Higher-level policies — those that are farthest from the inputs and outputs — tend to change less frequently, and for more important reasons, than low-level policies. Lower-level policies — those that are closest to the inputs and outputs — tend to change frequently, and with more urgency, but for less important reasons.

The purposes of an architecture

Good architectures are centered on the cases so that architects can safely describe the structures that support those use cases without committing to frameworks, tools, and environments. A good architecture emphasizes the use cases and decouples them from peripheral concerns.

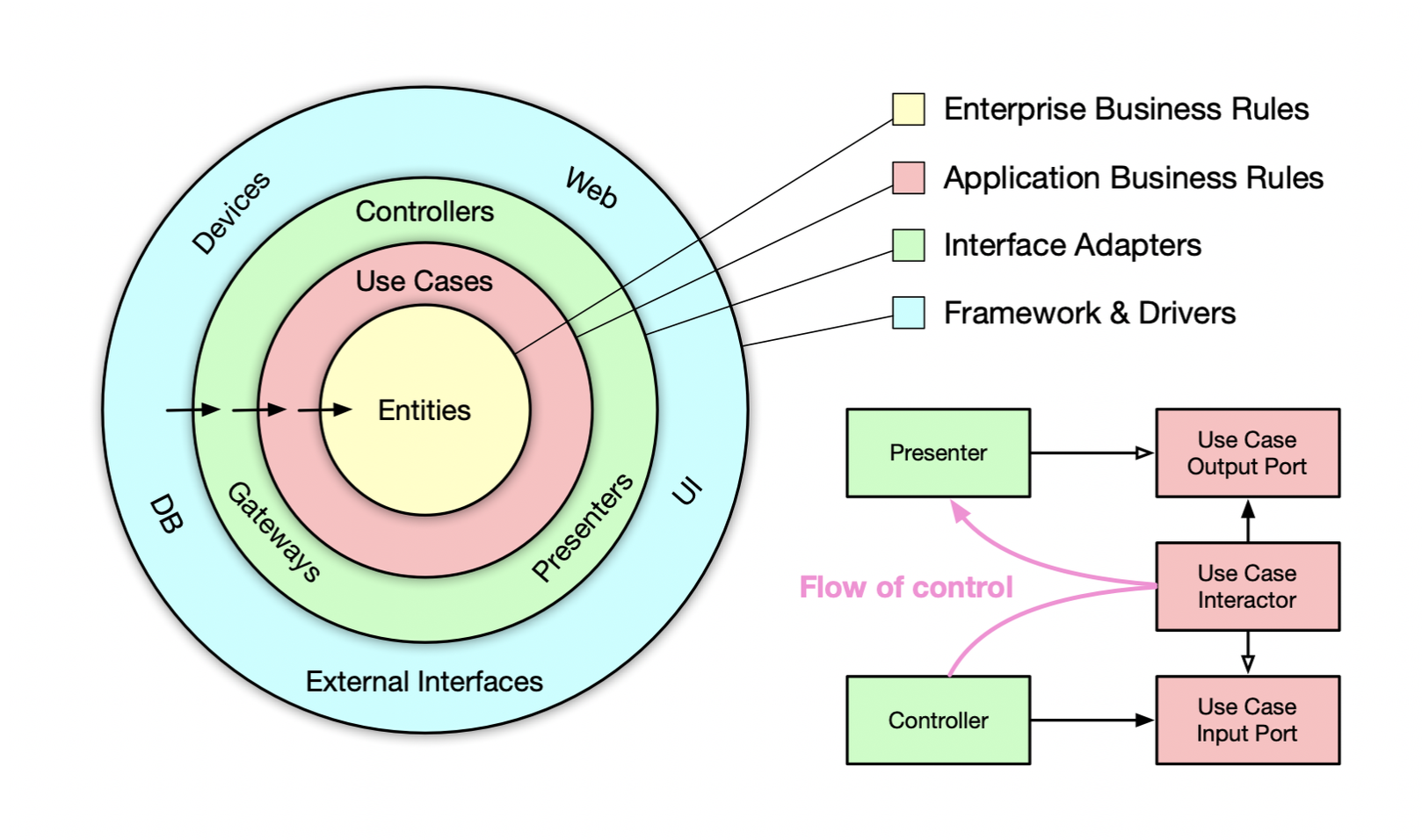

The clean architecture

- Independent of frameworks. The architecture does not depend on the existence of some library of feature-laden software.

- Testable. The business rules can be tested without the UI, database, web server, or any other external element.

- Independent of the UI. The UI can change easily, without changing the rest of the system.

- Independent of the database. Your business rules don't know anything at all about the interfaces to the outside world.

- Independent of any external agency. In fact, your business rules don't know anything at all about the interfaces.

Entities

Entities encapsulate enterprise-wide Critical Business Rules. An entity can be an object with methods, or it can be a set of data structures and functions.

Use cases

The use cases layer contains application-specific business rules. It encapsulates and implements all of the use cases of the system. These use cases orchestrate the flow of data to and from the entities, and direct those entities to use their Critical Business Rules to achieve the goals of the use case.

Interface adapters

The software in the interface adapters layer is a set of adapters that convert data from the format most convenient for the use cases and entities, to the format most convenient for some external agency such as the database or the web.

Frameworks and drivers

The frameworks and drivers layer is where all the details go. The web is a detail. The database is a detail.

Testing and architecture

It has long been known that testability is an attribute of good architectures.

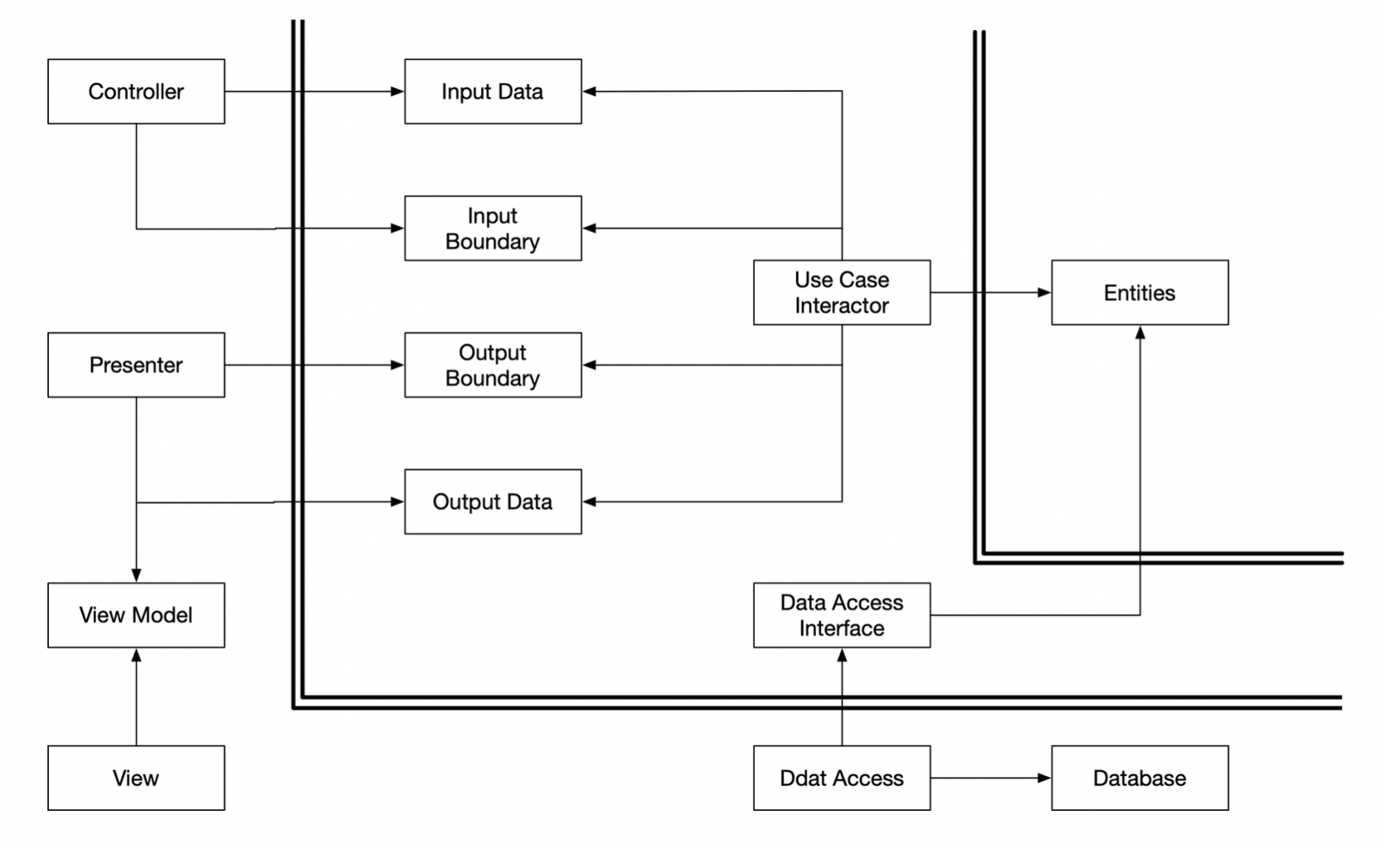

The humble object pattern Split the behaviors into two modules or classes. One of those modules is humble; it contains all the hard-to-test behaviors stripped down to their barest essence. The other module contains all the testable behaviors that were

The communication across each architectural boundary will almost always involve some kind of simple data structure, and the boundary will frequently divide something that is hard to test from something that is easy to test. The ues of this pattern at architectural boundaries vastly increases the testablility of the entire system.

Presenters and views

The view is the humble object that is hard to test. The code in this object is kept as simple as possible. It moves data into the GUI but does not process that data.

Database gateways

Don't directly embed data source logic into use cases. Use dadta gateways to obtain data and modify data.

Service listeners

The application will load data into simple data structure and then pass those structures across the boundary to modules that properly format the data and send it to external services.

Partial boundary

One way to construct a partial boundary is to do all the work necesssary to create inddependently compilable and deployable components, and then simply keep them together in the same component.

The test boundary

Tests, by their very nature, follow the Dependency Rule; they are very detailed and concrete; and they always depend inward toward the code being tested. In fact, you can think of the tests as the outermost circle in the architecture. Nothing within the system ddependds on the tests, and the tests always depend inward on the components of the system.

Details

The database is a detail.

The web is a detail.

The frameworks are details.

The relationship between you and the framework author is extraordinarily asymetric. You must make a huge commitment to the framework, but the framework author makes no commitment to you whatsoever.

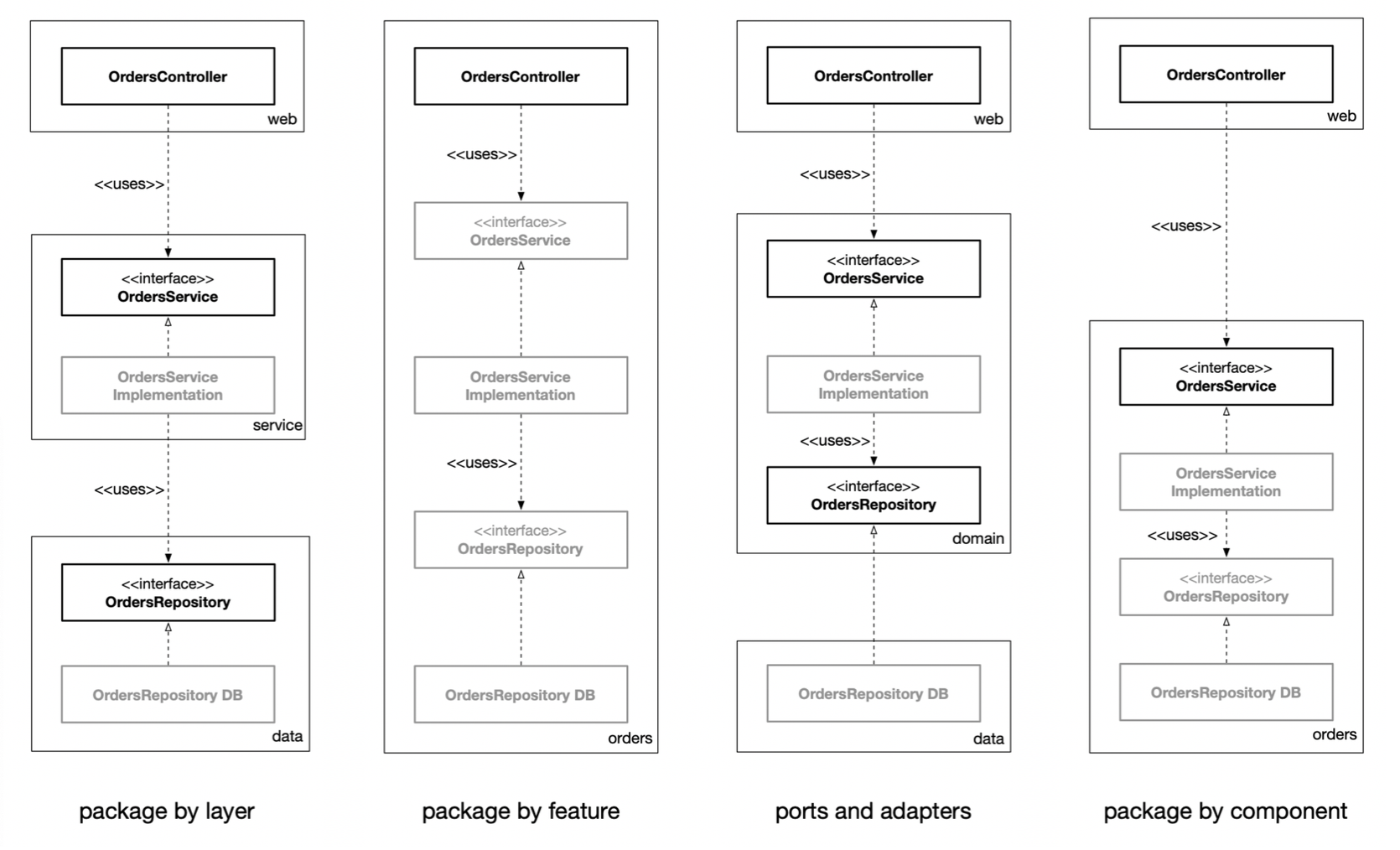

Four architecture approaches

Package by layer

This is the simplest traditional hoorizontal layered architecture. We have one layer for web, one layer for "business logic", and one layer for persistence.

Package by feature

This is a vertical slicing, based on related features, domain concepts, or aggregate roots. All of the types are placed into a single package, which is named to reflect the concept that is being grouped.

Ports and adapters

Approaches such as "ports and adapters", the "hexagonal architecture", "boundaries, controllers, entities" and so on aim to create architectures where business/domain-focused code is independent and separate from the technical implementation details such as frameworks and databasess.

Package by component

This approach bundles up the "business logic" and persistence code into a single thing, which is "a component".

Grayed-out types are where the access modifier can be made more restrictive.

Your best design intentions can be destroyed in a flash if you don't consider the intricacies of the implementation strategy. Think about how to map your desired design on to code structures, how to organize that code, and which decoupling modes to apply during runtime and compile-time. Leave options open where applicable, but be pragmatic, and take into consideration the size of your team, their skill level, and the complexity of the solution in conjunction with your time and budgetary consstraints. Also think about using your compiler to help your enforce your chosen architectural style, and watch out for coupling in other areas, such as data models. The devil is in the implementation details.